Scroll to:

Criteria for the existence of local equilibria in supercooled melts

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-607-612

Abstract

The paper is intended for researchers studying of supercooled metallic melts. It addresses an important theoretical problem: the possibility of establishing local thermodynamic equilibrium at the phase boundary during crystallization from a supercooled melt. Such processes play a crucial role in determining the microstructure of materials during solidification, particularly under rapid cooling conditions characteristic of modern metallurgical and powder technologies. During supercooling, nuclei of a new, solid phase begin to form in the melt. To mathematically describe the growth of such nuclei, it is necessary to specify boundary conditions that define the composition of the adjacent liquid phase. Traditional models assume that local equilibrium can be established near the nucleus and that its parameters can be derived from the equilibrium phase diagram. However, as demonstrated by our study of binary systems, local equilibrium may, in some cases, be fundamentally unattainable. This article presents a theoretical analysis of the conditions under which equilibrium may or may not be established. The analysis considers chemical potentials of the components in both the solid nucleus and the liquid melt. Based on the equilibrium phase diagram of the corresponding macrosystem, one can infer the relative chemical potentials of the components in each phase. It is shown that when the nucleus consists of a single component, local equilibrium is always possible in principle. However, when the nucleus is a solution, equilibrium may only be realized under specific thermodynamic conditions. In such cases, the application of first-kind boundary conditions becomes invalid, and it is necessary to take into account the rates of chemical reactions involved in the interphase transfer of each component.

Keywords

For citations:

Drozin A.D., Dudorov M.V. Criteria for the existence of local equilibria in supercooled melts. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):607-612. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-607-612

Introduction

The study of the kinetics of crystal nucleation and growth during rapid solidification of the melt has become particularly relevant in recent years due to the development of nanotechnologies and the wide use of amorphous alloys. To calculate the growth rates of nanocrystals [1 – 3] in a melt or, for instance, in an amorphous alloy during annealing [4 – 5], it is necessary to know the concentrations of the melt components at their surfaces.

The aim of this study is to provide a theoretical analysis of the conditions under which local equilibrium may (or may not) be established at the boundary between a solid nucleus and a supercooled melt.

Let us consider a case in which a binary metallic melt is instantaneously cooled to a temperature below the solidus. Nuclei of a new, solid phase begin to form within the melt. To formulate the differential equations describing the growth of such a nucleus, it is necessary to specify boundary conditions – that is, the concentrations of the liquid-phase components at the phase interface. Traditionally, it is assumed that any system tends to reach an equilibrium state, and although true equilibrium cannot exist in a supercooled liquid melt, it can be assumed that, at nanoscale distances from the nucleus, the composition of the liquid phase will be nearly equilibrium, i.e., local equilibrium is established. The parameters of this quasi-equilibrium are usually taken from the equilibrium phase diagram. However, our analysis shows that in many cases this assumption is not valid.

Our conclusions regarding deviations from local equilibrium are supported by the results of studies on the “solute trapping” effect caused by the high rate of crystal growth in the melt [6 – 9]. Theoretical studies by several authors [10 – 13], as well as our own research [14 – 15], have made it possible to identify certain regularities in these processes. Experimental studies of various systems [16 – 17], particularly supercooled metallic melts [18 – 20], confirm the manifestation of such effects in practice. Meanwhile, no general thermodynamic criteria have been formulated so far to assess the conditions of local equilibrium during crystal growth. This study focuses on analyzing these conditions.

To evaluate the equilibrium conditions, let us consider the processes associated with phase equilibrium through the chemical potentials of their components:

| \[{\mu _i} = \mu _i^0 + RT\ln {a_i},\] | (1) |

where \(\mu _i^0\) is the part of the chemical potential of the i-th component that does not depend on concentration, R is the universal gas constant, T is the temperature, and ai is the activity of the i-th component. For the sake of generality, we will use only the following properties of chemical potentials:

– the dependence of the activity of a component in the phase on the concentration of that component is a monotonically increasing continuous function;

– as the concentration of a component approaches zero, its activity likewise tends to zero; hence, by Eq. (1), its chemical potential tends to −∞, and the molar contribution of this component to the phase’s Gibbs free energy of mixing tends to zero.

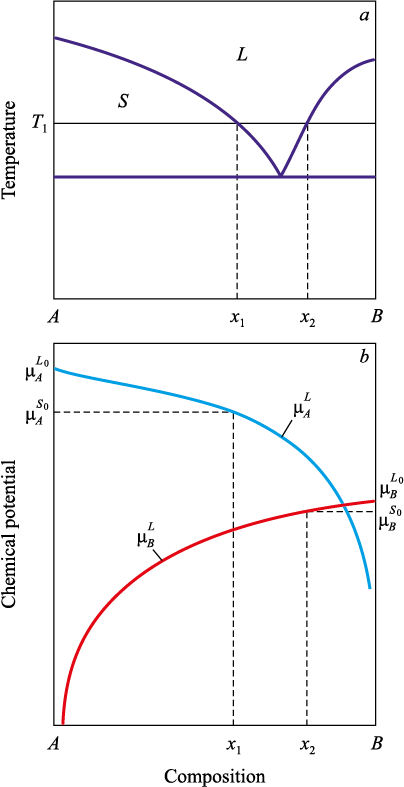

Binary system with equilibrium in one component

Consider a model case of a liquid solution (melt) of components A and B with an equilibrium phase diagram shown in Fig. 1 at temperature T1 . From the diagram, several conclusions can be drawn about the chemical potentials of the phase components. Since, at the fraction of component B corresponding to the pure component A, the system is at equilibrium in the solid state, the chemical potential of component A in the solid phase must be lower than in the liquid phase: \(\mu _A^{{S_0}} < \mu _A^{{L_0}}\). In accordance with the above considerations, let us draw the corresponding curve \(\mu _A^L = \mu _A^L(x)\).

Fig. 1. Chemical potentials of the components in a system |

Since, according to Eq. (1), as x → 1 the chemical potential \(\mu _A^L\) → –∞ and \(\mu _A^L\)(0) larger \(\mu _A^S\)(0), then by the Bolzano–Cauchy theorem for continuous functions [21] there exists a point x such that \(\mu _A^L\)(x) = \(\mu _A^{{S_0}}\). In the case shown in Fig. 1 at temperature T1 , this concentration is x1 .

Note that the same reasoning also applies to temperatures below the eutectic. Local equilibrium will be established between the solid-phase nucleus and the continuation of the liquidus line. This statement is applicable provided that an approximation (or an analytical expression) of the liquidus line below the solidus is available.

The analysis has been limited to component A because component B is absent in the nucleus and its chemical potential does not affect phase equilibrium. Similar reasoning can be carried out for the growth of a crystal of phase B.

According to Fig. 1, at temperature T1 nuclei of the pure component B are in local equilibrium with a solution of composition x2.

Binary system with equilibrium in both components

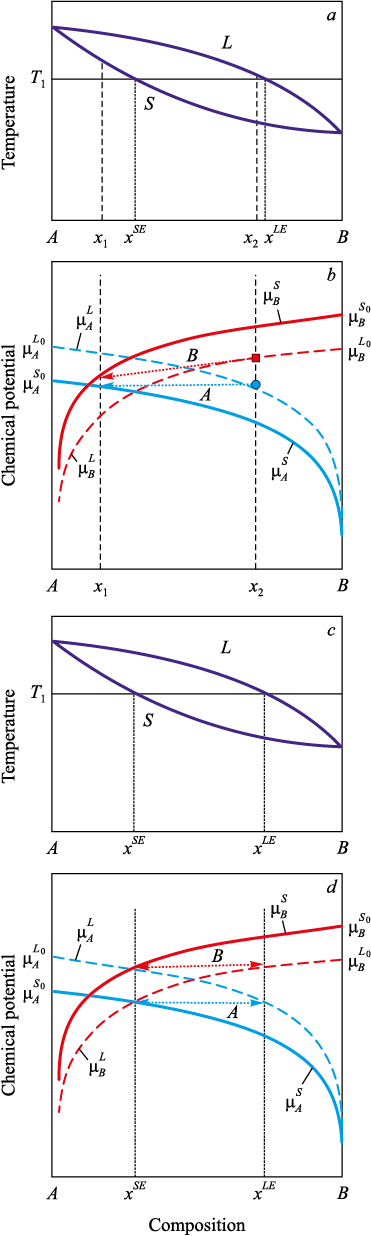

Consider a more complex case. Let components A and B exhibit unlimited mutual solubility in both the liquid and solid states, as represented by the phase diagram in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Chemical potentials of the components (a, c) in a system |

Based on the diagram (Fig. 2, a), we draw the required conclusions about the chemical potentials of the components at temperature T1 . Since, at the fraction of component B corresponding to the pure component A: x = 0, the system is at equilibrium in the solid state, the chemical potential of component A in the solid phase \(\mu _A^{{S_0}}\) must be lower than that in the liquid phase \(\mu _A^{{L_0}}\), as shown schematically in Fig. 2, b. In accordance with Eq. (1), we plot the curves \(\mu _A^L\) = \(\mu _A^L\)(x) and \(\mu _A^S\) = \(\mu _A^S\)(x). In the general case, the curve \(\mu _A^L\) should lie above and to the right of \(\mu _A^S\). We perform analogous constructions for component B. Since at x = 1 (pure B) the system is at equilibrium in the liquid state, the chemical potential of B in the liquid phase \(\mu _B^{{L_0}}\) must be lower than in the solid phase \(\mu _B^{{S_0}}\), as also shown in Fig. 2, b. According to Eq. (1), we then plot \(\mu _B^L\) = \(\mu _B^L\)(x) and \(\mu _B^S\) = \(\mu _B^S\)(x). In the general case, \(\mu _B^S\) should lie above and to the left of \(\mu _B^L\).

Note also that the mutual placement of the chemical-potential curves for A and B is immaterial for the present argument.

For the system to be in equilibrium with respect to component A, the compositions of the liquid and solid phases must satisfy \(\mu _A^L\left( {c_A^L} \right) = \mu _A^S\left( {c_A^S} \right)\). Geometrically, this means that the compositions defined by the intersection points of the curves \(\mu _A^L\)(x) and \(\mu _A^S\)(x) with any horizontal line correspond to A – equilibrium. There is an infinite set of such composition pairs.

However, for the system to be in equilibrium, equilibrium with respect to component B must also be achieved at the same concentrations. Thus, if the composition of the solid phase corresponds to point x1 in Fig. 2, b, then, despite the fact that the chemical potentials of component A in both phases are equal, equilibrium with respect to component B will not be attained. The chemical potential of component B in the liquid phase is higher than in the solid phase, and therefore a transfer of component B from the liquid phase into the solid phase will occur. This disrupts A – equilibrium and shifts the solid phase composition. In the case shown in Fig. 2, b, concentration redistribution enriches both phases in component B. The process terminates only when point x1 moves to position xSE and x2 moves to xLE.

Let us determine when true equilibrium – simultaneously in both components – is possible. At equilibrium the equalities and: \(\mu _A^L\left( {{x^L}} \right) = \mu _A^S\left( {{x^S}} \right)\) and \(\mu _B^L\left( {{x^L}} \right) = \mu _B^S\left( {{x^S}} \right)\), must hold at the same time. As seen in Fig. 2, c, d, this is necessary and sufficient for the chemical affinities of the transitions from the liquid to the solid phase for component A: \({a_A} = \mu _A^{{L_0}} - \mu _A^{{S_0}}\) and for component B: \({a_B} = \mu _B^{{L_0}} - \mu _B^{{S_0}}\) to have opposite signs, that is, either \(\left( {\mu _A^{{L_0}} < \mu _A^{{S_0}},\,\,\,\mu _B^{{L_0}} > \mu _B^{{S_0}}} \right)\), or \(\left( {\mu _A^{{L_0}} > \mu _A^{{S_0}},\,\,\,\mu _B^{{L_0}} < \mu _B^{{S_0}}} \right)\).

We now prove this mathematically. For simplicity, consider the case where the component activities are equal to the mole fractions. At equilibrium, the equalities must hold simultaneously: \(\mu _A^L\left( {{x^L}} \right) = \mu _A^S\left( {{x^S}} \right)\) and \(\mu _B^L\left( {{x^L}} \right) = \mu _B^S\left( {{x^S}} \right)\). Using Eq. (1), we can write these relations in the form:

| \[\begin{array}{c}\left\{ \begin{array}{l}\mu _A^{{L_0}} + RT\ln \left( {1 - {x^L}} \right) = \mu _A^{{S_0}} + RT\ln \left( {1 - {x^S}} \right),\\\mu _B^{{L_0}} + RT\ln {x^L} = \mu _B^{{S_0}} + RT\ln {x^S}\end{array} \right. \Rightarrow \\ \Rightarrow \left\{ \begin{array}{l}\frac{{1 - {x^L}}}{{1 - {x^S}}} = \exp \left( {\frac{{\mu _A^{{S_0}} - \mu _A^{{L_0}}}}{{RT}}} \right),\\\frac{{{x^L}}}{{{x^S}}} = \exp \left( {\frac{{\mu _B^{{S_0}} - \mu _B^{{L_0}}}}{{RT}}} \right).\end{array} \right.\end{array}\] | (2) |

Introduce the notation

| \[\begin{array}{c}A_A^0 = \mu _A^{{L_0}} - \mu _A^{{S_0}},\,\,\,A_B^0 = \mu _B^{{L_0}} - \mu _B^{{S_0}},\\{K_A} = \exp \left( { - \,\,\frac{{A_A^0}}{{RT}}} \right),\,\,{K_B} = \exp \left( { - \,\,\frac{{A_B^0}}{{RT}}} \right).\end{array}\] | (3) |

From system (2) it follows that it is impossible to have KA = 1 or KB = 1 or KA = KB , since in any of these cases one obtains KA = KB = 1 and xL = xS, that does not occur in this case.

Except for these cases, from Eq. (2) we obtain

| \[{x^S} = \frac{{{K_A} - 1}}{{{K_A} - {K_B}}},\,\,\,{x^L} = \frac{{{K_A} - 1}}{{{K_A} - {K_B}}}{K_B}.\] | (4) |

However, Eq. (4) may also yield physically meaningless results (negative values or values exceeding unity). Let us determine for which values of KA and KB the constrains 0 ≤ xS ≤ 1, 0 ≤ xL ≤ 1, are satisfied, i.e..

| \[0 \le \frac{{{K_A} - 1}}{{{K_A} - {K_B}}} \le 1,\,\,\,0 \le \frac{{{K_A} - 1}}{{{K_A} - {K_B}}}{K_B} \le 1.\] | (5) |

An analysis of the system of inequalities (5) shows that they hold when (KA < 1, KB > 1), or, conversely, (KA > 1, KB < 1). Using the notation of Eq. (3), we obtain that equilibrium in the system under consideration is possible if the chemical affinities \(A_A^0\) and \(A_B^0\) have opposite signs: if for one component, say A: \(\mu _A^{{L_0}}\) > \(\mu _A^{{S_0}}\), then for the other it must necessarily be the opposite: \(\mu _B^{{L_0}}\) < \(\mu _B^{{S_0}}\). Thus, the criterion for the possibility of local equilibrium is the set of conditions

| \[\left( {\mu _A^{{L_0}} < \mu _A^{{S_0}},\,\,\mu _B^{{L_0}} > \mu _B^{{S_0}}} \right)\] или \[\left( {\mu _A^{{L_0}} > \mu _A^{{S_0}},\,\,\,\mu _B^{{L_0}} < \mu _B^{{S_0}}} \right).\] | (6) |

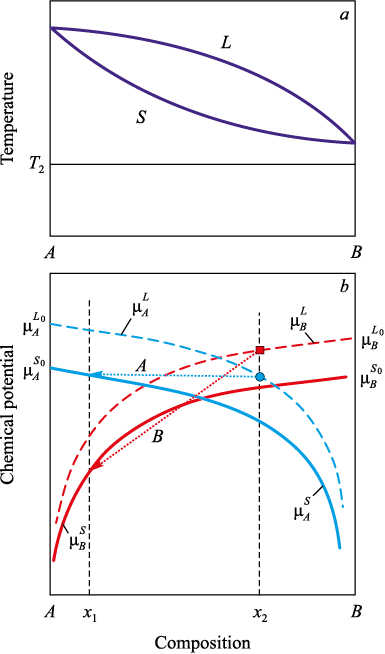

Let us consider the case where these conditions are not satisfied – namely, the same system at a temperature T2 below the solidus line (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Chemical potentials of the components (a) in a system |

At temperatures below the solidus, both components in the pure state are solid: \(\left( {\mu _A^{{L_0}} > \mu _A^{{S_0}},\,\,\mu _B^{{L_0}} > \mu _B^{{S_0}}} \right)\,\) so the necessary conditions for phase equilibrium are not fulfilled. This is evident from Fig. 3, since the \(\mu _A^{{L_0}}\) curve lies above and to the right of the \(\mu _A^{{S_0}}\) curve; at equilibrium with respect to component A one has xS < xL.

For component B, the \(\mu _B^{{L_0}}\) curve lies above and to the left of the \(\mu _B^{{S_0}}\) curve, and equilibrium with respect to component B is possible only if xL < xS. These conditions cannot be satisfied simultaneously – equilibrium is impossible.

Thus, at temperatures below the solidus, when both components are in the solid state, the equilibrium conditions for both components cannot be fulfilled simultaneously. The analysis shows that, in this case, any local equilibrium between the liquid and solid phases is impossible because it would require mutually contradictory values of the chemical potentials. Consequently, any analytic continuation of the equilibrium lines into the region of supercooled melts below the solidus has no thermodynamic justification and cannot be used to provide a correct description of phase transformations on supercooling.

Results and discussion

The aim of this work was to use equilibrium phase diagrams to study the dynamics of nucleation and growth of nuclei of a new phase. It is evident that under rapid cooling the system does not attain global equilibrium; however, in the vicinity of the solid – liquid interface a quasi-equilibrium local state may be established, which makes it possible to employ thermodynamic approaches. The use of local equilibria is a key principle of nonequilibrium thermodynamics.

The analysis shows that such local equilibria are not always possible. If the nucleus consists of a single component, a quasi-equilibrium description is applicable. For two or more components, the feasibility of local equilibrium is determined by the relative signs of the chemical affinities for the interphase transitions. In particular, if these affinities have the same sign, local equilibrium is impossible, and the phase transformations must be described exclusively by kinetic models.

The proposed approach can be extended to more complex systems, provided that functional dependences of phase activities on composition are available. For more accurate modelling of nucleus growth, the model should be supplemented with diffusion equations describing mass transport to the phase boundary and with rate equations governing the interphase chemical reactions that transfer components between the phases.

Conclusions

We have developed a method for determining the possibility of local equilibrium between a solid nucleus and the liquid (parent) phase based on an analysis of the chemical potentials of the components. With the necessary modifications, this approach can be applied to real multicomponent systems. In cases where the establishment of local equilibrium is impossible, a mathematical description of crystallization must include not only diffusion equations but also equations for the rates of interfacial chemical reactions for each component.

References

1. Tan L., Zabaras N. Modeling the growth and interaction of multiple dendrites in solidification using a level set method. Journal of Computational Physics. 2007;226(1):131–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2007.03.023

2. Boettinger W.J., Warren J.A., Beckermann C., Karma A. Phase-field simulation of solidification. Annual Review of Material Research. 2002;32:163–194. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.matsci.32.101901.155803

3. Drozin A.D. Growth of Microparticles of Chemical Reaction Products in a Liquid Solution. Chelyabinsk: SUSU; 2007:56. (In Russ.).

4. Herlach D.M., Galenko P.K., Holland-Moritz D. Metastable Solids from Undercooled Melts. Amsterdam; London: Elsevier; 2007:432.

5. Gamov P.A., Drozin A.D., Dudorov M.V., Roshchin V.E. Model for nanocrystal growth in an amorphous alloy. Russian Metallurgy (Metally). 2012;2012(11):1002–1006. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0036029512110055

6. Baker J.C., Gahn J.W. Solute trapping by rapid solidification. Acta Metallurgica. 1969;17(5):575–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6160(69)90116-3

7. Aziz M.J. Model for solute redistribution during rapid solidification. Journal of Applied Physics. 1982;53(2):1158–1168. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.329867

8. Aziz M.J., Kaplan T. Continuous growth model for interface motion during alloy solidification. Acta Metallurgica. 1988;36(8):2335–2347. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6160(88)90333-1

9. Jackson K.A., Beatty K.M., Gudgel K.A. An analytical model for non-equilibrium segregation during crystallization. Journal of Crystal Growth. 2004;271(3–4):481–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2004.07.073

10. Galenko P.K., Ankudinov V. Local non-equilibrium effect on the growth kinetics of crystals. Acta Materialia. 2019;168: 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2019.02.018

11. Galenko P.K., Jou D. Rapid solidification as non-ergodic phenomenon. Physics Reports. 2019;818:1–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2019.06.002

12. Sobolev S.L. Local non-equilibrium diffusion model for solute trapping during rapid solidification. Acta Materialia. 2012;60(6–7):2711–2718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2012.01.036

13. Lipton J., Glicksman M.E., Kurz W. Dendritic growth into undercooled alloy metals. Materials Science and Engineering. 1984;65(1):57–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0025-5416(84)90199-X

14. Drozin A.D., Dudorov M.V., Roshchin V.E., Gamov P.A., Menikhes L.D. Mathematical description of the nucleation in supercooled eutectic melt. Bulletin of SUSU. Mathematics. Mechanics. Physics. 2012;(11):66–72. (In Russ.).

15. Dudorov M.V., Drozin A.D., Roshchin V.E., Vyatkin G.P. Nonlinear theory of the growth of new phase particles in supercooled metal melts. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry. 2024;98:2447–2452. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0036024424701619

16. Pratap A., Lad K.N., Rao T.L.S., Majmudar P., Saxena N.S. Kinetics of crystallization of amorphous Cu50Ti50 alloy. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 2004;345–346:178–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2004.08.018

17. Khanolkar G.R., Rauls M.B., Kelly J.P., Graeve O.A., Hodge A.M., Eliasson V. Shock wave response of iron-based in situ metallic glass matrix composites. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1):22568. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22568

18. Yang C., Liu F., Yang G., Zhou Y. Structure evolution upon non-equilibrium solidification of bulk undercooled Fe–B system. Journal of Crystal Growth. 2009;311(2):404–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2008.11.025

19. Zhang D., Xu J., Liu F. In situ observation of the competition between metastable and stable phases in solidification of undercooled Fe-17at. pctB alloy melt. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A. 2015;46:5232–5239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-015-3104-0

20. Battezzati L., Antonione C., Baricco M. Undercooling of Ni-B and Fe-B alloys and their metastable phase diagrams. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 1997;247(1–2):164–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-8388(96)02570-4

21. Fikhtengol’ts G.M. Course of Differential and Integral Calculus: in 3 vols. Vol. 1. Moscow: Fizmatlit; 2003:680 p. (In Russ.).

About the Authors

A. D. DrozinRussian Federation

Aleksandr D. Drozin, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Prof., Leading Researcher of the Research Laboratory “Hydrogen Technologies in Metallurgy”

76 Lenina Ave., Chelyabinsk 454080, Russian Federation

M. V. Dudorov

Russian Federation

Maksim V. Dudorov, Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Senior Researcher of the Research Laboratory “Hydrogen Technologies in Metallurgy”

76 Lenina Ave., Chelyabinsk 454080, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Drozin A.D., Dudorov M.V. Criteria for the existence of local equilibria in supercooled melts. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):607-612. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-607-612