Scroll to:

Surface engineering of Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 amorphous alloy by excimer laser

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-598-606

Abstract

The problem of differences in surface quality exists in the production of amorphous alloy (AA) ribbons by ultra-fast single-roll melt spinning. Structural inhomogeneities that can disrupt the isotropy of properties occur on the side of the ribbons adjacent to the quenching drum. In this regard, there is a need to develop a promising surface modification technology of AA which will not only eliminate roughness, but also controllingly manage the structure along the ribbon depth, as well as selective processing of its individual sections to improve mechanical, magnetic and catalytic characteristics. Application of short-pulse laser systems has great potential for achieving these goals. In this research work, the effect of an excimer ultraviolet laser operating in nanometer wavelength range on the structural evolution, mechanical behavior and morphological changes of the surface of Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 AA with varying the pulse number and their frequency were comprehensively studied using profilometry, indentation, optical and transmission electron microscopy methods. It is shown that laser irradiation of the contact matte side of the studied AA ribbon according to the selected mode (100 pulses, f = 20 Hz, E = 150 mJ, W = 0.6 J/cm2) effectively acts upon the surface relief and smoothes out production irregularities (pores, gas lines, scratches, etc.). In addition, the laser processing parameters are established that contribute to the AA structure softening, and therefore improve workability for possible forming, as well as the mode of transfer AA to an amorphous-nanocrystalline state with increased hardness and preservation of the ability to flow shear.

Keywords

For citations:

Permyakova I.E., Ivanov A.A., Lukina I.N., Kostina M.V., Dyuzheva-Maltseva E.V. Surface engineering of Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 amorphous alloy by excimer laser. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):598-606. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-598-606

Introduction

Amorphous alloys (AAs) are deeply supercooled materials characterized by a glass transition temperature, below which an energetically unstable non-crystalline state prevails [1; 2]. This structural feature provides a combination of ductility with excellent strength, hardness, and an elastic limit of up to 2 % due to the absence of long-range order [3 – 5]. In addition to their outstanding mechanical characteristics, a number of AAs exhibit high magnetic properties, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility, which makes them attractive for various applications [6 – 9]. Existing fabrication methods for AAs, such as copper mold casting and melt spinning, are effective in retaining the glassy state but are subject to significant limitations in terms of scalability, critical dimensions, and geometric complexity. Moreover, AAs are difficult-to-machine materials with a narrow range of thermal stability and a tendency to become brittle at elevated temperatures [10; 11]. These challenges drive the search for more advanced technologies for the production and processing of AAs in order to expand their engineering applications. In recent years, research has increasingly focused on the fundamental study of structural modification, phase formation, and property response in AAs under laser irradiation [12 – 14]. The introduction of selective laser melting with ultra-high cooling rates is a highly promising method for producing bulk AAs [15 – 18]. Laser-induced periodic surface structuring of AAs makes it possible to:

– produce color through the formation of oxide films of different thicknesses [19];

– tune hydrophobic/hydrophilic behavior in wettability tests [20];

– control domain structure and magnetic behavior [21];

– reduce friction and wear in tribological applications [22];

– fabricate precision diffraction gratings for sensor devices and related applications [23].

Surface functionalization of AAs therefore has the potential to broaden their application range and to introduce new functionalities into AA-based components.

Pulsed laser processing offers such advantages as high peak power and energy density, controlled thermal effects, rapid heating and cooling, high precision, and minimal deformation of the material compared with continuous-wave lasers [14; 24]. The pulse duration determines the degree of thermal diffusion, which plays an important role for nanosecond lasers, in contrast to femtosecond lasers that primarily induce phonon relaxation [25; 26]. Nanosecond laser treatment, characterized by larger affected zones and greater penetration depth, makes it possible to tune the magnetic behavior of AAs and to modify their mechanical properties by changing the surface microstructure [27 – 30]. However, several important questions remain to be addressed, for example:

– how to develop adequate physical models describing the interaction of short-pulse laser irradiation with AAs in the absence of a detailed understanding of the underlying mechanisms;

– whether improved material properties can be achieved by forming gradient amorphous–crystalline composite structures through pulsed laser treatment;

– how to design the structure of AAs in a controlled and efficient way and which laser parameters should be considered optimal.

At present, numerous studies are underway on pulsed laser processing of bulk AAs based on zirconium, titanium, and copper. In contrast, for rapidly quenched iron-based amorphous ribbons, the available data are limited, fragmented, and call for further exploratory investigation. It should be emphasized that iron-based AAs deserve particular attention due to the low cost of raw materials, their outstanding mechanical and soft magnetic characteristics, and excellent catalytic activity. Optimization of laser irradiation parameters to improve the functional properties of such alloys and to control their structure therefore remains an important research objective.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the effect of excimer ultraviolet laser irradiation operating in the nanometer wavelength range on structural and phase transformations, mechanical response, and morphological changes at the surface of Fe – Ni – B amorphous alloy under variation of pulse number and frequency.

Materials and methods

The object of study was a rapidly quenched Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 amorphous alloy produced by the melt-spinning method in the form of a ribbon 10 mm wide and 25 μm thick.

Laser irradiation of the AA samples was performed using an excimer ultraviolet (UV) KrF laser of the CL-7100 series (Optosystems, Russia) with a wavelength of λ = 248 nm and a pulse duration of τ = 20 ns. The irradiation was applied through a circular diaphragm with an area of S = 7 mm2 at two pulse modes 100 and 500 pulses – while varying the repetition frequency f from 2 to 50 Hz. In both cases, the pulse energy E was 150 mJ, and the energy density W was 0.6 J/cm2. The contact matte side of the AA ribbon, i.e., the side that was in contact with the copper quenching drum during fabrication, was subjected to laser treatment.

Hardness HIT was measured using a DUH-211S dynamic ultramicrohardness tester (Shimadzu, Japan). Indentation was carried out in accordance with ISO 14577, employing a Vickers diamond indenter under a load of 10 mN in a loading–unloading mode at a rate of 70 mN/s.

Structural characterization of the AA was performed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a JEM-2100 microscope (JEOL, Japan).

The surface morphology of the laser-irradiated areas was examined with a GX51 inverted metallographic microscope (Olympus, Japan). Surface roughness was evaluated according to GOST 2789 – 73 using a NewView 7300 profilometer (Zygo, USA).

esults and discussion

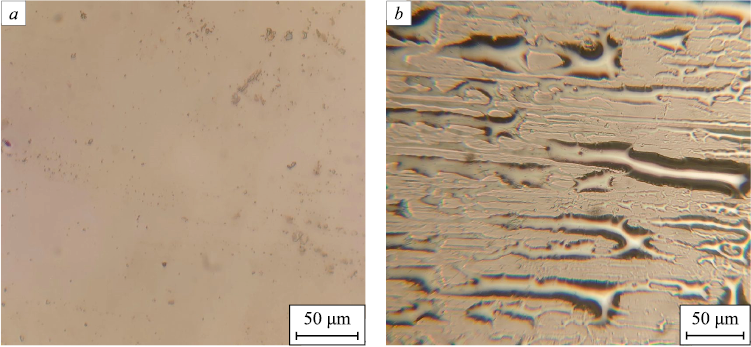

Figure 1 shows the appearance of both sides of the Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 amorphous alloy ribbon in its as-fabricated state. Unlike the non-contact side, which has a mirror-like surface (Fig. 1, a), the contact side exhibits extended surface irregularities such as dimples, cavities, and gas streaks elongated along the ribbon axis (Fig. 1, b). The formation of this microrelief is associated with the interaction of the melt puddle with the boundary gas layer on the non-ideal surface of the copper quenching drum [31]. These defects create internal stresses that adversely affect the magnetic response of the alloy [32 – 34]. Therefore, developing a laser modification technique and selecting an effective mode for smoothing the rough surface of amorphous ribbons, while improving their wear resistance and maintaining the amorphous structure, are essential research tasks.

Fig. 1. Morphology of non-contact (a) and contact (b) sides of the ribbon of Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 |

After excimer UV laser irradiation under the first mode, surface transformations of the AA were examined (Fig. 2).

Рис. 2. Морфология облученной поверхности АС Fe53,3Ni26,5B20,2 |

The results show that laser processing contributes to the elimination of surface roughness on the contact side of the ribbon. However, at a frequency of 2 Hz, the process proceeds unevenly. In the center of the irradiated circular area, a distinct “healing” of irregularities is observed (Fig. 2, a), while toward the periphery, large surface defects often remain unaffected by the laser (Fig. 2, b).

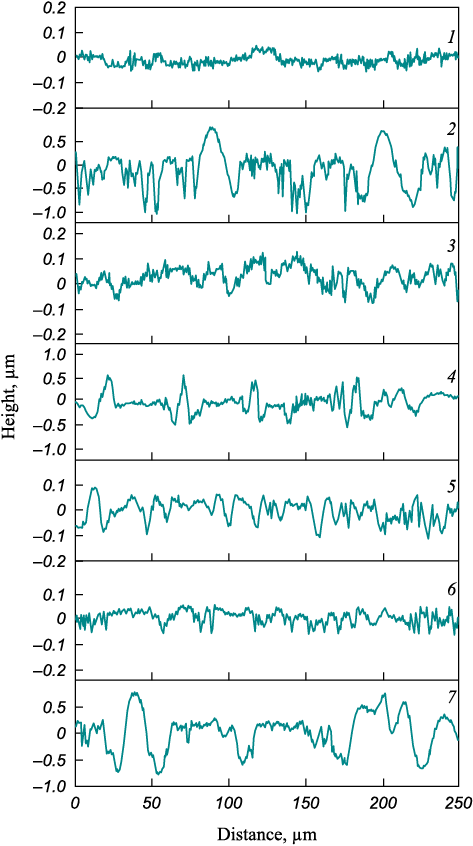

At frequencies ranging from 10 to 50 Hz, the laser impact becomes more uniform across the entire irradiated zone (Fig. 2, c – e), although the degree of reduction in surface height irregularities (parameter Rz ) varies. Fig. 3 presents profilometry results for the ribbon in both the initial state and the laser-irradiated regions shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The surface topography was scanned perpendicular to the ribbon axis.

Fig. 3. Surface profilograms of the ribbon of Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 |

The best smoothing effect, including the collapse of volumetric accumulations of gas streaks, was achieved at a pulse repetition frequency of 20 Hz (Fig. 2, d; curve 6 in Fig. 3).

The calculated surface-relief data are summarized in the Table, confirming that 20 Hz is the optimal frequency for laser modification aimed at leveling the contact side of the ribbon and bringing its quality closer to that of the ideally smooth non-contact side, which corresponds to the highest (13th) surface roughness class.

Surface profilometry parameters of Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 amorphous alloy

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

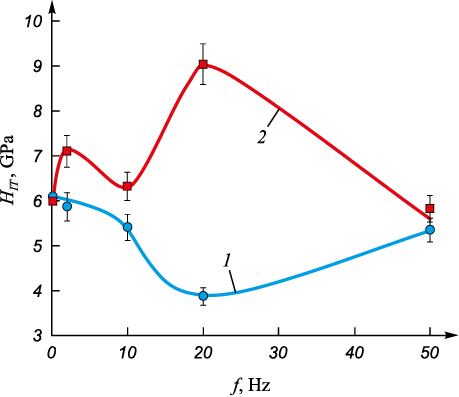

Subsequently, the mechanical response of the alloy was evaluated by measuring hardness after laser irradiation. Under 100-pulse irradiation, an increase in pulse frequency leads to material softening (Fig. 4, curve 1). At f = 20 Hz, the hardness HIT decreases by approximately 35 % relative to the initial value (HIT0 = 6 GPa) of the untreated alloy. At f = 50 Hz, HIT slightly increases to 5.4 GPa.

Fig. 4. Laser frequency dependence of hardness of Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 amorphous alloy: |

When the number of pulses increases to 500, the dependence HIT (f) exhibits a more complex behavior, with two pronounced maxima at 2 and 20 Hz (Fig. 4, curve 2). At f = 50 Hz, a softening effect is observed – the hardness decreases to 5.8 GPa, approaching the value obtained for 100-pulse irradiation at the same frequency.

Thus, it can be concluded that excimer laser treatment at 100 pulses, f = 20 Hz, E = 150 mJ, W = 0.6 J/cm2 is an effective way to enhance the plasticity of the amorphous alloy. The mechanism underlying the hardness decrease observed for curve 1 in Fig. 4 can be interpreted as follows. During irradiation, short laser pulses with high energy density propagate from the surface into the material, generating an intense shock wave [12; 13]. When the peak pressure of the shock wave exceeds the yield strength, the amorphous alloy undergoes plastic deformation. The formation of a residual stress regions containing shear bands and free volume form within the ribbon is facilitated, resulting in improved plasticity [14].

In contrast, irradiation under the 500-pulse mode (curve 2 in Fig. 4) at E = 150 mJ and W = 0.6 J/cm2 leads to optimal hardening within the amorphous state at f = 2 Hz and to maximum hardening within the amorphous–nanocrystalline state at f = 20 Hz, as confirmed by TEM observations.

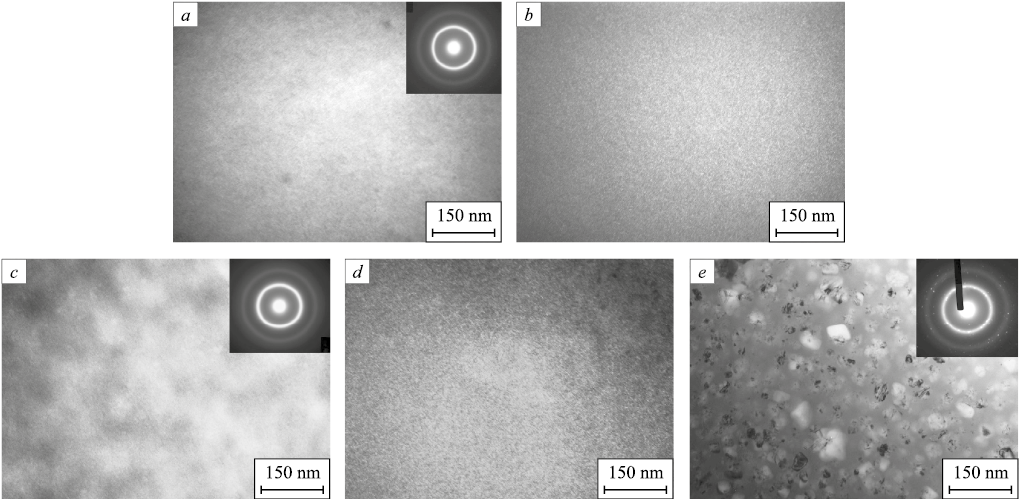

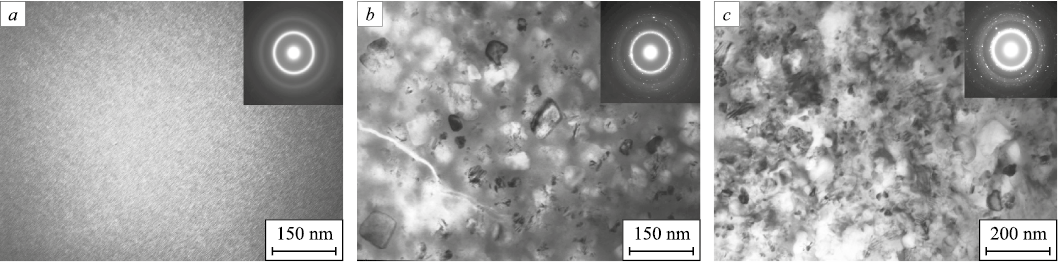

Figs. 5 and 6 present TEM images illustrating the structural evolution of the studied alloy as a function of pulse number and frequency.

Fig. 5. TEM images and the corresponding selected area electron diffraction patterns

Fig. 6. TEM images and the corresponding selected area electron diffraction patterns |

Under the first laser processing mode (100 pulses), the amorphous structure is preserved within the frequency range f = 2 – 20 Hz (Fig. 5, a – d). The selected area electron diffraction patterns show two diffuse halos characteristic of the amorphous phase, while the TEM images display a characteristic fine “salt-and-pepper” contrast that remains essentially unchanged when switching from bright-field to dark-field imaging. However, at f = 20 Hz, a slight disturbance of the homogeneous contrast is observed (Fig. 5, c), accompanied by halo broadening, which indicates the onset of structural rearrangement preceding crystallization. The amorphous matrix locally reorganizes, facilitating plastic deformation processes. This structural relaxation manifests itself as a decrease in the hardness parameter HIT . At this irradiation frequency, the free volume undergoes rearrangement and coalescence, promoting the formation and propagation of shear bands.

At f = 50 Hz, nanocrystals of α-Fe with a BCC lattice and γ-Fe with an FCC lattice precipitate within the amorphous matrix, with a total volume fraction of about 40 % (Fig. 5, e). The nanocrystal size ranges from 20 to 70 nm. The coexistence of amorphous and nanocrystalline phases leads to an increase in hardness.

Under the second irradiation mode (500 pulses), the transition from the amorphous (Fig. 6, a) to the amorphous – nanocrystalline state occurs at lower frequencies, i.e., at f = 20 Hz (Fig. 6, b). The coexistence of two structural components, together with high hardness, provides conditions for the development of plastic shear. In Fig. 6, b, the propagation of shear bands is visible, including their looping, branching, and braking on nanocrystals.

An increase in pulse repetition frequency to f = 50 Hz stimulates crystallization processes in the alloy. Along with the formation of crystalline α, γ-(Fe,Ni), and eutectic γ-(Fe, Ni) + Fe3B phases, grain growth is observed (Fig. 6, c), which leads to softening, i.e., a decrease in HIT (curve 2 in Fig. 4).

Conclusions

Nanosecond excimer UV lasers offer significant advantages for low-cost, environmentally friendly, high-precision, and selective processing of amorphous alloys with minimal material loss. They ensure efficient energy transfer and can achieve high laser energy densities. With properly selected parameters, such treatment can activate either structural rejuvenation of the amorphous alloy – accompanied by loosening and softening that improve workability and formability – or partial crystallization aimed at achieving optimal strength combined with satisfactory plasticity.

It has been demonstrated that excimer UV laser irradiation of the contact (matte) side of the rapidly melt-quenched Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 amorphous alloy ribbon under the selected mode (100 pulses, f = 20 Hz, E = 150 mJ, W = 0.6 J/cm2) most effectively modifies the surface relief, reduces roughness, and eliminates manufacturing defects such as pores and gas streaks formed during melt spinning.

A nonmonotonic dependence of the HIT hardness of Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 on the laser pulse repetition frequency was established. Irradiation with 100 pulses at 20 Hz produces a pronounced softening effect while preserving the amorphous structure. Atomic rearrangements occur without long-range diffusion. Increasing the pulse number to 500 leads to energy accumulation within the material and intensified laser heating, resulting in a two-stage hardening at 2 and 20 Hz followed by a hardness drop at 50 Hz. This behavior is associated with a transition from structural relaxation in the amorphous alloy (involving local topological and compositional ordering) to crystallization processes characterized by nucleation and emergence of crystalline phases and grain growth.

References

1. Sohrabi S., Fu J., Li L., Zhang Y., Li X., Sun F., Ma J., Wang W.H. Manufacturing of metallic glass components: Processes, structures and properties. Progress in Material Science. 2024;144:101283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2024.101283

2. Greer A.L., Costa M.B., Houghton O.S. Metallic glasses. MRS Bulletin. 2023;48:1054–1061. https://doi.org/10.1557/s43577-023-00586-5

3. Glezer A.M., Permyakova I.E. Melt-quenched nanocrystals. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2013:369. https://doi.org/10.1201/b15028

4. Qiao J.C., Wang Q., Pelletier J.M., Kato H., Casalini R., Crespo D., Pineda E., Yao Y., Yang Y. Structural heterogeneities and mechanical behavior of amorphous alloys. Progress in Materials Science. 2019;104:250–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.04.005

5. Schuh C.A., Hufnagel T.C., Ramamurty U. Mechanical behavior of amorphous alloys. Acta Materialia. 2007;55(12): 4067–4109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2007.01.052

6. Biały M., Hasiak M., Łaszcz A. Review on biocompatibility and prospect biomedical applications of novel functional metallic glasses. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2022;13(4):245. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb13040245

7. Gao K., Zhu X.G., Chen L., Li W.H., Xu X., Pan B.T., Li W.R., Zhou W.H., Li L., Huang W., Li Y. Recent development in the application of bulk metallic glasses. Journal of Materials Science and Technology. 2022;131:115–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2022.05.028

8. Jiang L., Bao M., Dong Y., Yuan Y., Zhou X., Meng X. Processing, production and anticorrosion behavior of metallic glasses: A critical review. Journal Non-Crystalline Solids. 2023;612:122355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2023.122355

9. Permyakova I.E., Dyuzheva-Maltseva E.V. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on structural transformations and mechanical behaviour of amorphous alloys (REVIEW). Frontier Materials & Technologies. 2025;(2):53–71. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.18323/2782-4039-2025-2-72-5

10. Permyakova I., Glezer A. Mechanical behavior of Fe- and Co-based amorphous alloys after thermal action. Metals. 2022;12(2):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12020297

11. Glezer A.M., Potekaev A.I., Cheretaeva A.O. Thermal and time stability of amorphous alloys. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2017:180. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315158112

12. Permyakova I.E., Ivanov A.A., Chernogorova O.P. Modification of amorphous alloys using laser technologies. In: Actual Problems of Strength. Rubanik V.V. ed. Minsk: IVTs Minfina; 2024:124–139. (In Russ.).

13. Williams E., Lavery N. Laser processing of bulk metallic glass: А review. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2017;247:73–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2017.03.034

14. Ren J., Wang D., Wu X., Yang Y. Laser-based additive manufacturing of bulk metallic glasses: A review on principle, microstructure and performance. Materials & Design. 2025;252:113750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2025.113750

15. Zhang P., Tan J., Tian Y., Yan H., Yu Z. Research progress on selective laser melting (SLM) of bulk metallic glasses (BMGs): A review. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2022;118(7–8):2017–2057. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-021-07990-8

16. Pauly S., Löber L., Petters R., Stoica M., Scudino S., Kühn U., Eckert J. Processing metallic glasses by selective laser melting. Materials Today. 2013;16(1–2):37–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2013.01.018

17. Frey M., Wegner J., Barreto E.S., Ruschel L., Neuber N., Adam B., Riegler S.S., Jiang H.-R., Witt G., Ellendt N., Uhlenwinkel V., Kleszczynski S., Busch R. Laser powder bed fusion of Cu-Ti-Zr-Ni bulk metallic glasses in the Vit101 alloy system. Additive Manufacturing. 2023;66:103467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2023.103467

18. Kosiba K., Kononenko D.Y., Chernyavsky D., Deng L., Bednarcik J., Han J., J. van den Brink, Kim H.J., Scudino S. Maximizing vitrification and density of a Zr-based glass-forming alloy processed by laser powder bed fusion. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2023;940(3):168946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.168946

19. Jiang H., Shang T., Xian H., Sun B., Zhang Q., Yu Q., Bai H., Gu L., Wang W. Structures and functional properties of amorphous alloys. Small Structures. 2020;2(2):2000057. https://doi.org/10.1002/sstr.202000057

20. Jiao Y., Brousseau E., Shen X., Wang X., Han Q., Zhu H., Bigot S., He W. Investigations in the fabrication of surface patterns for wettability modification on a Zr-based bulk metallic glass by nanosecond laser surface texturing. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2020;283:116714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2020.116714

21. Talaat A., Greve D.W., Leary A., Liu Y., Wiezorek J., Ohodnicki P.R. Laser patterning assisted devitrification and domain engineering of amorphous and nanocrystalline alloys. AIP Advances. 2022;12(3):035313. https://doi.org/10.1063/9.0000314

22. Wu H., Liang L., Lan X., Yin Y., Song M., Li R., Liu Y., Yang H., Liu L., Cai A., Li Q., Huang W. Tribological and biological behaviors of laser cladded Ti-based metallic glass composite coatings. Applied Surface Science. 2020;507(21):145104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.145104

23. Gnilitskyi I.M., Mamykin S.V., Lanara C., Hevko I., Dusheyko M., Bellucci S., Stratakis E. Laser nanostructuring for diffraction grating based surface plasmon-resonance sensors. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(3):591. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11030591

24. Grigor’yants A.G., Shiganov I.N., Misyurov A.I. Technological Processes of Laser Treatment. Grigor’yants A.G. ed. Moscow: Bauman MSTU; 2008:664. (In Russ.).

25. Zhang W., Zhang P., Yan H., Li R., Shi H., Wu D., Sun T., Luo Z., Tian Y. Research status of femtosecond lasers and nanosecond lasers processing on bulk metallic glasses (BMGs). Optics & Laser Technology. 2023;167:109812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2023.109812

26. Rethfeld B., Sokolowski-Tinten K., D. von der Linde, Anisimov S.I. Timescales in the response of materials to femtosecond laser excitation. Applied Physics A. 2004;79:767–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-004-2805-9

27. Qian Y., Jiang M., Zhang Z., Huang H., Hong J., Yan J. Microstructures and mechanical properties of Zr-based metallic glass ablated by nanosecond pulsed laser in various gas atmospheres. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2022;901:163717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2022.163717

28. Guo L., Geng S., Yan Z., Chen Q., Lan S., Wang W. Nanocrystallization and magnetic property improvement of Fe78Si9B13 amorphous alloys induced by magnetic field assisted nanosecond pulsed laser. Vacuum. 2022;199:110983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2022.110983

29. Liu B., Hong J., Qian Y., Zhang H., Huang H. Simultaneous improvement in surface quality and hardness of laser shock peened Zr-based metallic glass by laser polishing. Optics & Laser Technology. 2024;179:111323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2024.111323

30. Li Y., Zhang K., Wang Y., Tang W., Zhang Y., Wei B., Hu Z. Abnormal softening of Ti-metallic glasses during nanosecond laser shock peening. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2020;773:138844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2019.138844

31. Kekalo I.B. Amorphous Magnetic Materials. Part. I. Moscow: NUST “MISIS”; 2001:276.

32. Wang Y., Kronmüller H. The influence of the surface conditions on the magnetic properties in amorphous alloys Fe40Ni40Be20 and Co58Ni10Fe5Si11Be16 . Physica Status Solidi A. 1988;70(2):415–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssa.2210700208

33. Ferrara E., Stantero A., Tiberto P., Baricco M., Janickovic D., Kubicar L., Duhaj P. Magnetic properties and surface roughness of Fe64Co21B15 amorphous ribbons quenched from different melt temperatures. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 1997;226–228:326–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-5093(96)10639-0

34. Kekalo I.B., Mogil’nikov P.S. The influence of spinning conditions on the quality of surface and magnetic properties of amorphous alloy ribbons Co58Fe5Ni10Si11B16 with low magnetostriction. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2014;57(7):51–56. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2014-7-51-56

About the Authors

I. E. PermyakovaRussian Federation

Inga E. Permyakova, Dr. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Leading Researcher of the Laboratory of Physicochemistry and Mechanics of Metallic Materials

49 Leninskii Ave., Moscow 119334, Russian Federation

A. A. Ivanov

Russian Federation

Andrei A. Ivanov, Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Assist. Prof. of the Chair “Solid State and Nanosystems Physics”

Moscow Engineering Physics Institute) (31 Kashirskoe Route, Moscow 115409, Russian Federation

I. N. Lukina

Russian Federation

Iraida N. Lukina, Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Senior Researcher of the Laboratory of Structural Steels and Alloys

49 Leninskii Ave., Moscow 119334, Russian Federation

M. V. Kostina

Russian Federation

Mariya V. Kostina, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Assist. Prof., Leading Researcher, Head of the Laboratory of Physicochemistry and Mechanics of Metallic Materials

49 Leninskii Ave., Moscow 119334, Russian Federation

E. V. Dyuzheva-Maltseva

Russian Federation

Elena V. Dyuzheva-Maltseva, Postgraduate of the Laboratory оf Physicochemistry and Mechanics of Metallic Materials

49 Leninskii Ave., Moscow 119334, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Permyakova I.E., Ivanov A.A., Lukina I.N., Kostina M.V., Dyuzheva-Maltseva E.V. Surface engineering of Fe53.3Ni26.5B20.2 amorphous alloy by excimer laser. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):598-606. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-598-606