Scroll to:

Production of carbide steels based on high-speed steel by induction surfacing

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-581-586

Abstract

The work is devoted to the study of the possibility of obtaining carbide steel based on powdered high-speed steel 10R6M5 with additives of tungsten (WC) and titanium (TiC) carbides by induction surfacing. The selected compositions of the deposited charge and the proposed composition of the flux based on fused borax with additives of boric acid and a number of oxides satisfy the technology. The developed technology includes a flux, a method of briquetting charge using a piston device that minimizes the movement of ferromagnetic components of the charge under the influence of inductor electromagnetic field during surfacing. Deposited layers of carbide steel based on high-speed steel reinforced with tungsten and titanium carbides were produced and studied. The obtained layers were analyzed using optical and electron microscopy (using a microanalyzer), phase composition of the deposited layers was controlled by the X-ray phase method, and hardness of the layers was measured by the Rockwell method. Addition of tungsten carbide to powdered high-speed steel leads to the formation of ledeburite structure during surfacing, which is characteristic of high-tungsten high-speed steels. An increase in the amount of tungsten carbide in the carbide steel leads only to its partial melting in liquid steel, which helps to preserve the particles of introduced carbides in the microstructure. Titanium carbide added to the carbide steel composition significantly changes the morphology of ledeburite precipitates. According to X-ray phase analysis data, a number of carbides of Me12C, Me6C, Me2C and MeC types were observed in the composition of carbide steels, which are characteristic of carbide steels obtained by various methods (plasma surfacing, sintering, impregnation of a carbide frame, etc.). It is shown that hardness of the samples of carbide steels with additives of tungsten and titanium carbides varies from 59 to 63 HRC, depending on the composition and technological modes of surfacing.

Keywords

For citations:

Klimov S.A., Noskov F.M., Tokmin A.M., Masanskii O.A. Production of carbide steels based on high-speed steel by induction surfacing. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):581-586. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-581-586

Introduction

The development of new structural and tool materials with improved physicomechanical and operational properties has become increasingly important. This need arises from the limited potential to further enhance the characteristics of well-known materials such as wear-resistant [1 – 3] and tool steels (including high-speed steels), as well as hard alloys [4 – 6].

Carbide steels, consisting of refractory carbides (most often tungsten and titanium carbides) and steels, represent a new class of promising materials. They occupy an intermediate position between hard alloys and steels, combining the properties of both the carbide reinforcing phase and the steel matrix [7 – 9].

Carbide steels are most commonly produced by powder metallurgy methods, including sintering of compacted powders, impregnation of a carbide frame with steel, hot pressing, or hot extrusion [7]. However, these processes involve numerous complex technological operations, which limit their practical use. Alternative approaches such as plasma [10 – 13] or laser [14; 15] have also been investigated, but these methods are constrained by the high cost of laser systems, loss of powder due to plasma jet scattering, and consumption of expensive gases. The key factor limiting the widespread application of carbide steels remains the complexity of conventional production technologies, which require sophisticated equipment and long process cycles.

Induction surfacing of metallic layers [16 – 20], based on high-frequency current heating, has recently become a promising alternative. Under the multifactor influence of the inductor electromagnetic field on the metal substrate, flux, and initial charge, a a multilayer composite is formed, in which a surface layer may be formed that exhibits a set of improved properties, including wear resistance, acid resistance, heat resistance, and so on. This method is characterized by relatively low equipment costs, simplicity of implementation, and short processing times.

Moreover, the surfacing process can be partially combined with heat treatment of the deposited layer if necessary. The present study aimed to investigate the possibility of producing carbide steel by induction surfacing.

The main objectives were to:

– select suitable compositions of the deposited charge based on high-speed steel with tungsten and titanium carbide additives for induction surfacing;

– develop a flux composition for induction surfacing of carbide steel;

– produce deposited layers of carbide steel based on high-speed steel reinforced with tungsten and titanium carbides on steel substrateх;

– analyze the microstructure and properties of the obtained samples.

Materials and methods

Powdered high-speed steel 10R6M5 was used as the main component of the charge for producing the deposited layers. To obtain carbide steel, the powdered steel was mixed on an organic binder with tungsten carbide (WC) and titanium carbide (TiC) powders in various proportions (5 – 20 wt. % relative to steel). The upper limit was deliberately set below the conventional range (20 – 70 wt. %) [7], because induction surfacing is characterized by considerably shorter heating times compared with traditional processes, and, consequently, the available time for interaction between the matrix and the reinforcing phase is also reduced. Consequently, excessive amounts of reinforcing carbides were avoided to ensure effective component interaction and a defect-free structure.

Flux plays an essential role in induction surfacing, protecting both the molten metal and the surface of the steel substrate from oxidation by atmospheric oxygen [9]. The flux mixture consisted of powdered fused borax, boric acid, and oxide additives of silicon, magnesium, calcium, and sodium.

During flux selection, the influence of the magnetic field generated in the surfacing zone on the charge was taken into account. One of the challenges in producing carbide steel based on high-speed steel is the ferromagnetism of powdered steel, which interacts strongly with the electromagnetic field at the initial heating stage (before the transition to a paramagnetic state). To prevent displacement of the powder charge under these conditions, the mixture was compacted into briquettes. The flux also acts as a kind of binder, holding the charge particles together within the temperature range in which the flux was already molten while the metallic part of the charge had not yet fused.

A piston-type compaction system proved most effective for briquetting. The mixed charge components were placed into a container pre-lubricated with a plasticizer based on an organic compound, which reduced adhesion of the components to the container walls and the piston. Compaction was performed by applying pressure with the piston, during which excess binder and plasticizer could be released. The briquettes were then dried for at least 2 h at 80 °C.

Plates of medium-carbon structural steel 45 were used as substrates.

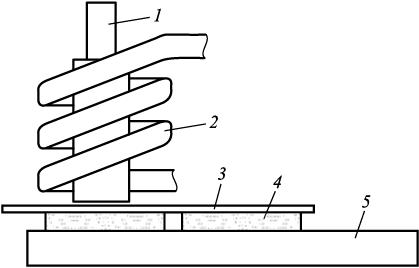

Surfacing of the plates (Fig. 1) was carried out using a high-frequency induction unit of the UVG 2-25 type equipped with a GNOM-25M1 generator, with a power output of up to 20 kW and an operating frequency of 44 to 66 kHz. A coil inductor with a water-cooled ferrite core was used. To fix the briquettes at the initial stage of surfacing and protect the inductor, an asbestos gasket was placed between the briquette and the substrate (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Scheme of induction surfacing: |

Microstructural studies were conducted using a Carl Zeiss Axio Observer.D1 optical microscope and a Hitachi TM4000 scanning electron microscope with a microanalyzer. The phase composition was examined by X-ray phase analysis using a Bruker diffractometer with copper radiation. The hardness of the deposited layers was measured by the Rockwell method.

Results and discussion

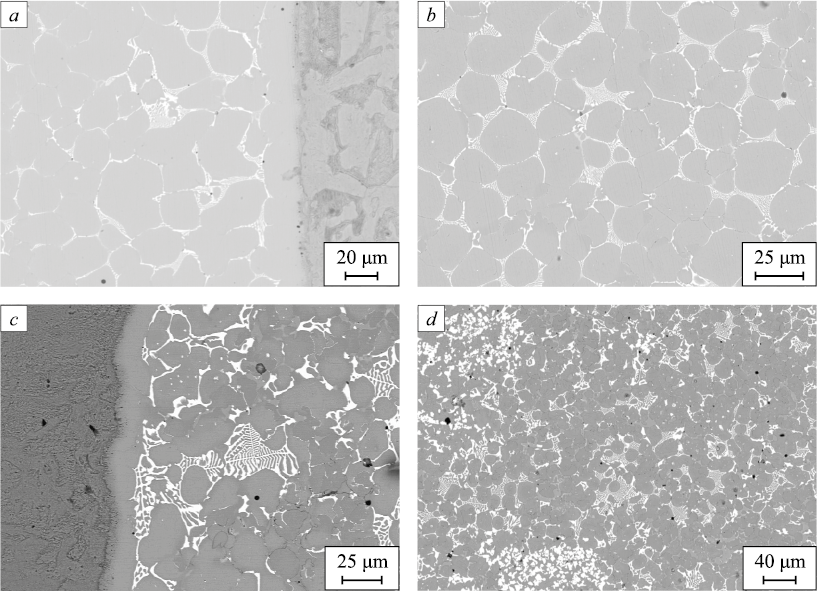

Microstructural analysis of the deposited layers revealed that the overall structure corresponds to the characteristic features of cast high-speed steel. All samples contained ledeburite eutectic of varying morphology depending on the composition and carbide content in the charge. A solid solution based on austenite was also present, its composition varying widely depending on the alloy composition.

When powdered high-speed steel 10R6M5 was surfaced without additives (Fig. 2, a), a typical cellular structure was observed, with small inclusions of ledeburite eutectic of feather-like morphology. The addition of a small amount of tungsten carbide led to its almost complete dissolution in the melt; the resulting solidified structure resembled that of high-speed steel without additives (Fig. 2, b), but with a higher amount of feather-like ledeburite eutectic.

Fig. 2. Microstructure of deposited layers: |

A further increase in the amount of added carbides leads to the formation of ledeburite eutectic with the so-called skeletal morphology, characteristic of high-tungsten high-speed steel of the R18 type (Fig. 2, c). This is explained by the dissolution of the added carbides in the liquid steel during surfacing. However, because of the short duration of the process, the solubility limit is apparently governed not so much by the constraints of the phase diagram as by the insufficient time for complete interaction. As a result, a structure may be identified in which, along with the skeletal eutectic, clusters of undissolved tungsten carbide particles with a characteristic angular shape are observed (Fig. 2, d).

According to X-ray phase analysis, the structure contained austenite, martensite, cementite, and ledeburite with carbides of the Fe6W6C and Fe3W3C types. In addition, X-ray phase analysis revealed carbide inclusions of the W2C and WC types, the latter representing partially partially undissolved particles of the introduced carbide phase remaining in the solid solution in samples with a relatively high content of added carbides.

Hardness tests showed that deposited 10R6M5 layers without reinforcement exhibited 60 – 61 HRC, while those with tungsten carbide additions reached 61 – 63 HRC.

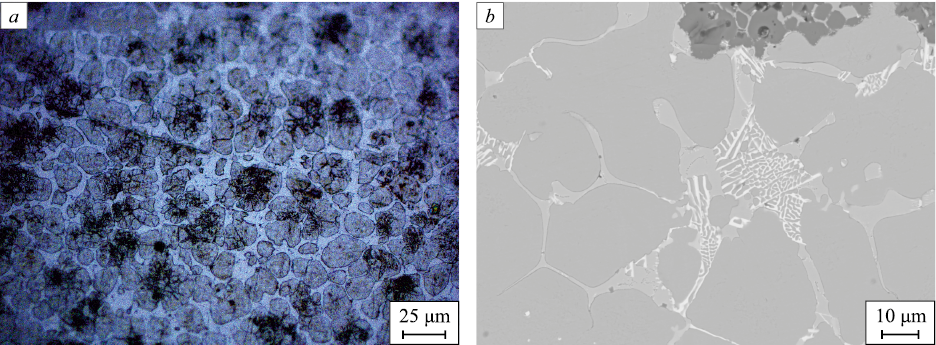

Producing carbide steel based on high-speed steel reinforced with titanium carbide (TiC) proved more difficult. This was due to the specific nature of the wetting of titanium carbide by molten steel, as well as mutual dissolution between the matrix and the reinforcing phase, among other factors [7]. Nevertheless, deposited layers of carbide steel with TiC were successfully obtained. Their microstructures (Fig. 3) varied depending on TiC content.

Fig. 3. Structure of carbide steel 10R6M5 – TiC: |

At low TiC concentrations (Fig. 3, a), the structure consisted of austenitic cells with a carbide network and visible martensite. No skeletal ledeburite was observed. As the TiC content increased, the deposition quality decreased and the tendency to pore formation became more pronounced; inclusions of ledeburite appeared with an intricate “Arabic script” morphology (Fig. 3, b). These features are apparently due to the ability of molten steel to dissolve only a limited amount of the introduced carbides and from the specific solidification behavior of the melt.

X-ray phase analysis of TiC-containing samples revealed austenite, martensite, cementite, and ledeburite with carbides of Fe6W6C and Fe3W3C types. Alongside titanium carbide TiC, carbide inclusions of W2C were also identified.

The hardness of these samples ranged from 59 to 63 HRC.

Conclusions

Compositions of the deposited charge suitable for induction surfacing based on high-speed steel 10R6M5 with up to 20 wt. % tungsten carbide (WC) and titanium carbide (TiC) were selected. A flux composition for induction surfacing of carbide steel was developed, comprising borax and boric acid as the base components, with oxide additives of silicon, magnesium, calcium, and sodium. A complete induction surfacing technology was designed and successfully applied to produce deposited layers of carbide steel based on high-speed steel reinforced with tungsten and titanium carbides on steel 45 substrates. The microstructure of the obtained samples contained austenite, martensite, cementite, and a number of special carbides, including those of the Me6C, Me2C, and MeC types. The hardness of the deposited carbide steel layers varied from 59 to 63 HRC, depending on the composition of the initial charge.

Thus, the feasibility of producing carbide steel based on powdered high-speed steel 10R6M5 with tungsten and titanium carbide additives by induction surfacing has been demonstrated.

References

1. Tarraste M., Kübarsepp J., Juhani K., Mere A., Kolnes M., Viljus M., Maaten B. Ferritic chromium steel as binder metal for WC cemented carbides. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2018;73:183–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2018.02.010

2. Chang S.-H., Chen S.-L. Characterization and properties of sintered WC–Co and WC–Ni–Fe hard metal alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2014;585:407–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.09.188

3. Fernandes C.M., Senos A.M.R., Vieira M.T., Antunes J.M. Mechanical characterization of composites prepared from WC powders coated with Ni rich binders. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2008;26(5):491–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2007.12.001

4. Savinykh L.M., Dudorova T.A., Pomyalov S.Yu., Verzhbalovich T.A. Increasing the efficiency of agricultural machinery repair based on the use of tools from carbide steel. Vestnik Kurganskoj GSHA. 2022;(4(44)):73–80. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.52463/22274227_2022_44_73

5. Garcia J. Influence of Fe–Ni–Co binder composition on nitridation of cemented carbides. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2012;30(1):114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2011.07.012

6. Chang S.H., Chang M.H., Huang K.T. Study on the sintered characteristics and properties of nanostructured WC-15 wt% (Fe-Ni-Co) and WC-15 wt% Co hard metal alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2015;649:89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.07.119

7. Kulkov S.N., Gnyusov S.F. Carbide Steels Based on Titanium and Tungsten Carbides. Tomsk: Izdatel’stvo nauchno-tekhnicheskoi literatury; 2006:239. (In Russ.).

8. Zhang Z., Wang X., Zhang Q., Liang Y., Ren L., Li X. Fabrication of Fe-based composite coatings reinforced by TiC particles and its microstructure and wear resistance of 40Cr gear steel by low energy pulsed laser cladding. Optics & Laser Technology. 2019;119:105622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2019.105622

9. Ortiz A., García A., Cadenas M., Fernández M.R., Cuetos J.M. WC particles distribution model in the cross-section of laser cladded NiCrBSi + WC coatings, for different wt% WC. Surface and Coatings Technology. 2017;324:298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2017.05.086

10. Ryzhkin A.A., Ilyasov A.V. Phase content of metal-matrix composites of the system Fe-W-C which are formed by plasma precipitation. Vestnik of the Don State Technical University. 2007;7(2(33)):169–176 (In Russ.).

11. Liu L.M., Xiao J.K., Wei X.L., Ren Y.X., Zhang G., Zhang C. Effects of temperature and atmosphere on microstructure and tribological properties of plasma sprayed FeCrBSi coatings. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2018;753:586–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.04.247

12. Emamian A., Alimardani M., Khajepour A. Correlation between temperature distribution and in situ formed microstructure of Fe-TiC deposited on carbon steel using laser cladding. Applied Surface Science. 2012;258(22):9025–9031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.05.143

13. Liu A.G., Guo M.H., Hu H.L., Li Z.J. Microstructure of Cr3C2-reinforced surface metal matrix composite produced by gas tungsten arc melt injection. Scripta Materialia. 2008;59(2):231–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2008.03.012

14. Muvvala G., Karmakar D.P., Nath A.K. In-process detection of microstructural changes in laser cladding of in-situ Inconel 718/TiC metal matrix composite coating. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2018;740:545–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.12.364

15. Muvvala G., Karmakar D.P., Nath A.K. Online assessment of TiC decomposition in laser cladding of metal matrix composite coating. Materials & Design. 2017;121:310–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2017.02.061

16. Tkachev V.N., Fishtein B.M., Kazintsev N.V., Aldyrev D.A. Induction Surfacing of Hard Alloys. Moscow: Mashinostroenie; 1970:177 (In Russ.).

17. Rudnev V.I., Loveless D. Induction hardening: Technology, process design, and computer modeling. Comprehensive Materials Processing. 2014;12:489–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-096532-1.01217-6

18. Malikov V.N., Ishkov A.V., Voynash S.A., Sokolova V.A., Remshev E.Yu. Investigation of processes of hardening steel parts by induction surfacing. Metallurg. 2021;(11):69–75. (In Russ.).

19. Bol’ A.A., Ivanaiskii V.V., Leskov S.P., Timoshenko V.P. Induction Surfacing, Technology, Materials, Equipment. Barnaul: Alt. NTO Mashinostroeniya; 1991:148. (In Russ.).

20. Mishra A., Bag S., Pal S. Induction heating in sustainable manufacturing and material processing technologies – A state of art literature review. Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering. 2020;1:343–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803581-8.11559-0

About the Authors

S. A. KlimovRussian Federation

Stepan A. Klimov, Postgraduate of the Chair of Materials Science and Materials Processing Technology

79 Svobodnyi Ave., Krasnoyarsk 660041, Russian Federation

F. M. Noskov

Russian Federation

Fedor M. Noskov, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Prof. of the Chair Materials Science and Materials Processing Technology

79 Svobodnyi Ave., Krasnoyarsk 660041, Russian Federation

A. M. Tokmin

Russian Federation

Aleksandr M. Tokmin, Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Prof. of the Chair of Materials Science and Materials Processing Technology

79 Svobodnyi Ave., Krasnoyarsk 660041, Russian Federation

O. A. Masanskii

Russian Federation

Oleg A. Masanskii, Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Assist. Prof., Head of the Chair of Materials Science and Materials Processing Technology

79 Svobodnyi Ave., Krasnoyarsk 660041, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Klimov S.A., Noskov F.M., Tokmin A.M., Masanskii O.A. Production of carbide steels based on high-speed steel by induction surfacing. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):581-586. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-581-586