Scroll to:

Hardening of surface layers of long rail head during long-term operation

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-572-580

Abstract

Starting in 2018, JSC EVRAZ United West Siberian Metallurgical Plant (EVRAZ ZSMK) produced rails of the DT400IK category with increased wear resistance and cyclic crack resistance for heavy traffic and difficult sections of track with steep curves with a radius of less than 650 m. The method of transmission diffraction electron microscopy was used to study the structural and phase states and defect substructure at different distances (0, 2, 10 mm) from the “wheel – rail” contact surface along the central axis of symmetry of the rail head (tread surface) and along the radius of rounding of the rail head (fillet) of differentially hardened long rails of the DT400IK category made of hypereutectoid steel after long-term operation on the experimental ring of Russian Railways (passed tonnage of 187 million tons). Based on the obtained structure parameters, the quantitative estimates were made of the dislocation substructure and main strengthening mechanisms (strengthening of the pearlite component, incoherent cementite particles, grain boundaries and subboundaries, dislocation substructure and internal stress fields) in various morphological components and in the material as a whole, forming the additive yield strength in the studied steel. A comparison of the quantitative parameters of the fine structure and contributions to strengthening on the tread surface and fillet was carried out. It was established that near the “wheel – rail” contact on the tread surface the prevailing morphological component is the subgrain structure, in the fillet – a ferrite-carbide mixture (completely destroyed pearlite). Strength of the rail head metal depends on the distance to the “wheel – rail” contact surface. It is shown that the main strengthening mechanisms on the tread surface are strengthening by internal stress fields, in the fillet – strengthening by incoherent particles.

Keywords

For citations:

Popova N.A., Gromov V.E., Yur’ev A.B., Nikonenko E.L., Porfir’ev M.A. Hardening of surface layers of long rail head during long-term operation. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):572-580. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-572-580

Introduction

According to data from the Russian Railways (RZhD), the primary causes of rail failure and subsequent withdrawal from service are contact fatigue damage and surface wear. These defects markedly reduce rail service life and directly affect traffic safety [1]. In recent years, a pronounced increase in axle loads and operating speeds in railway transport has been observed, which makes the development of rails with enhanced operational performance particularly relevant [2 – 5]. During service, the surface layers of rails undergo substantial structural and phase transformations [5 – 7]. These changes are accompanied by high microhardness values, decarburization [8 – 10], and the progression of relaxation, recrystallization, and related processes, which ultimately lead to the degradation of mechanical properties [11 – 13].

Increasing the carbon content in rails beyond 0.8 wt. % reduces the interlamellar spacing and promotes the formation, in the surface layers, of a subgrain structure with a high fraction of low-angle boundaries [14 – 17]. This approach can therefore be regarded as one of the promising strategies for mitigating contact fatigue [18 – 21].

Since 2018, Russia has been producing long, differentially hardened special-purpose rails with enhanced wear resistance and contact fatigue endurance – DT400IK category rails made of hypereutectoid steel – at EVRAZ ZSMK. These rails are intended for operation at speeds of up to 200 km/h on both straight and curved track sections without restrictions on traffic load intensity [22 – 24].

The scientific literature contains very few studies addressing rails made of hypereutectoid steel; existing works mainly report qualitative changes [25 – 30]. It is known that for rails with a carbon content below 0.8 wt. %, long-term operation leads to more pronounced evolution of the proportions of various morphological structure types, fine structure parameters, and cementite content at the fillet than at the tread surface [31; 32].

The aim of the present study is to provide a comparative assessment of the quantitative fine structure parameters and deformation strengthening mechanisms in the surface layers of the rail head – specifically, the tread surface and the fillet – of hypereutectoid steel rails after long-term operation (passed tonnage: 187 million tons, gross).

Materials and methods

The samples were taken from differentially hardened DT400IK category rails made of E90KhAF steel manufactured by EVRAZ ZSMK. The rails had accumulated a passed tonnage of 187 million tons (gross) in service on the experimental ring of Russian Railways (RZhD) in Shcherbinka. The internal structure and phase composition were examined in these samples. According to GOST 5185–2013 and TU 24.10.75111-298-057576.2017, the chemical composition of E90KhAF rail steel was (wt. %): 0.92 C, 0.4 Si, 1.0 Mn, 0.3 Cr, 0.14 V, balance Fe.

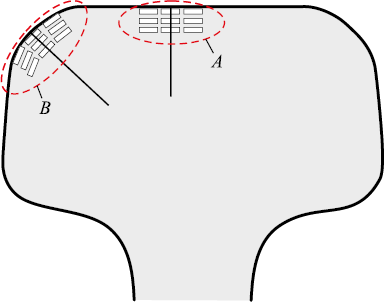

Two sets of the samples, A and B, were cut from the rails (Fig. 1). Set A was sampled along the central axis of symmetry of the rail head, corresponding to the tread surface (Fig. 1). Set B was taken along the radius of rounding of the rail head, i.e., from the fillet (Fig. 1). The samples from both sets were produced by electrical discharge cutting at identical distances from the wheel – rail contact surface, namely 0 mm (the uppermost layer of the contact surface), 2 and 10 mm below the surface. The studies were carried out using transmission diffraction electron microscopy (TEM) on thin foils, employing a JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Japan) at operating magnifications ranging from 15,000 to 500,000×.

Fig. 1. Scheme of foil preparation during examination by electron diffraction microscopy |

For each sample, the morphological components of the microstructure were classified, the phase composition was established, and the key fine structure parameters were quantified, including the volume fractions of the identified components. The distribution of the carbide phase (cementite) was also mapped, and for each location the particle shape, particle size, interparticle spacing, and volume fraction were determined. Dislocation characteristics were quantified as the scalar dislocation density (ρ) and the excess dislocation density (ρ± ), together with the amplitudes of internal stresses: (σF the shear (“forest”) stress generated by the dislocation structure, and σL the long-range (local) stress associated with regions of excess dislocation density. All quantitative fine structure parameters were determined both for each morphological component and for the material as a whole, followed by statistical processing. The methodology for determining these quantitative parameters is described in detail in [33; 34]. On the basis of the obtained data, and according to the authors of [33; 35; 36], the principal strengthening mechanisms contributing to the formation of the yield strength of the investigated steel were evaluated for each sample set.

Results and discussion

Previous studies [33; 34; 36] showed that, at a depth of 10 mm from the wheel – rail contact surface along the central axis of symmetry (the tread surface), the microstructure of the steel after long-term operation is dominated by pearlite with different morphologies. This includes lamellar (ideal) pearlite with nearly parallel α-phase and cementite lamellae, partially destroyed (defective) pearlite with bent and locally broken cementite lamellae, and globular pearlite. Together, these pearlitic constituents account for about 80 % of the structure. The remaining 20 % is represented by fragmented lamellar pearlite, in which dislocation walls form transverse to the α-phase lamellae; the average fragment size is approximately 90×420 nm. Representative micrographs of these morphological components are given in [33; 34; 36].

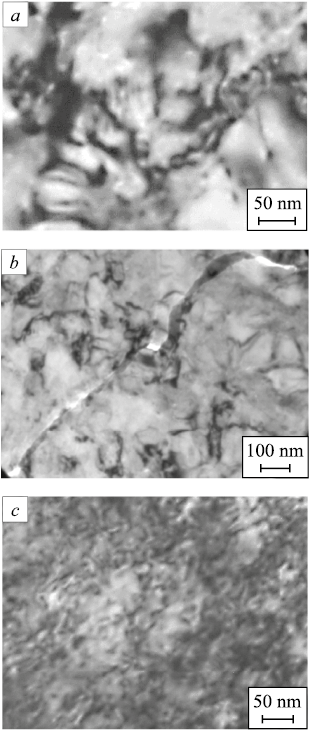

With decreasing distance to the wheel – rail contact surface, pearlite undergoes progressive degradation, while the fragmented structure becomes more refined and its characteristic dimensions decrease. Under these conditions, a subgrain structure forms and develops rapidly (Fig. 2, a). At the contact surface, this structure consists predominantly of dislocation-free subgrains with an average size of about 80 nm, occupying nearly 90 % of the material volume.

Fig. 2. TEM images of the subgrain structure (a) and microcracks |

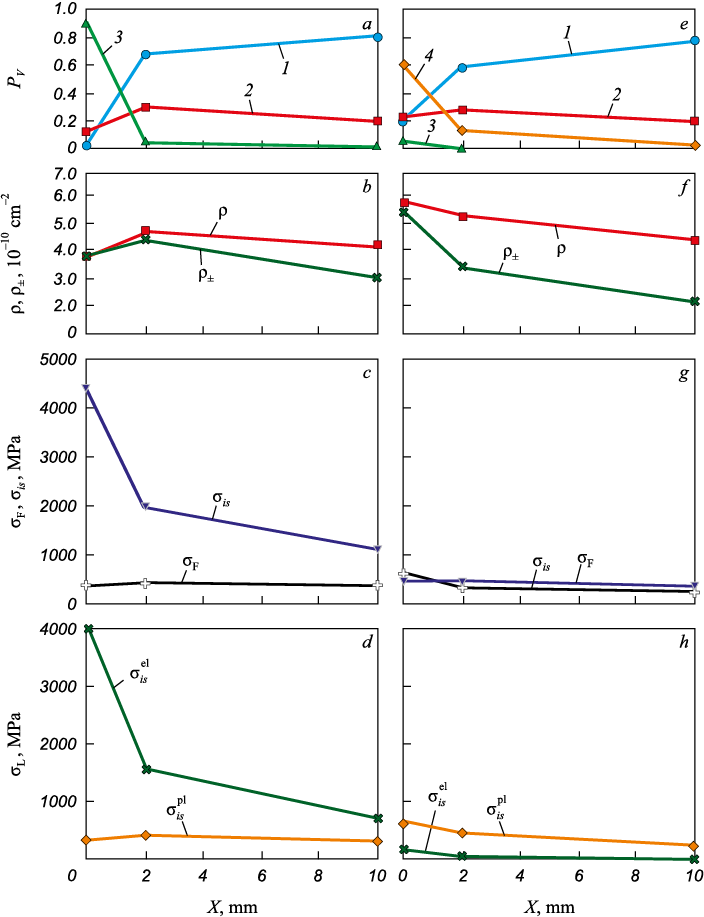

Service exposure is accompanied by the breakup and redistribution of cementite particles and by a slight increase in both the scalar and excess dislocation densities, followed by their decrease as the dislocation-free subgrain structure begins to develop intensively. The fragmentation of lamellar pearlite and the formation of the subgrain structure lead to elastic distortion of the α-phase crystal lattice. As a result, the amplitude of the long-range internal stresses σL , associated with regions of excess dislocation density, becomes approximately 4.5 times higher than that of the internal shear stresses σF generated by the dislocation structure. At the contact surface, the elastic component of these long-range stresses exceeds the plastic component by more than an order of magnitude, which provides the primary driving force for microcrack initiation within the subgrain structure (Fig. 2, b). The evolution of the average quantitative fine structure parameters with decreasing distance from the wheel–rail contact surface is summarized in Fig. 3, a – d.

Fig. 3. Dependences of quantitative parameters of fine structure on the distance |

In contrast to the central axis of symmetry (the tread surface), the steel structure along the radius of rounding of the rail head (the fillet) at the same depth from the wheel – rail contact surface (10 mm) contains, in addition to pearlite of various morphologies and fragmented lamellar pearlite, an additional morphological component. The volume fractions of pearlite and fragmented lamellar pearlite at this depth are close to those observed at the tread surface (78 and 20 %, respectively). The additional component, present in a small amount (approximately 2 %), is a ferrite – carbide mixture, representing regions with completely destroyed pearlite colonies (Fig. 2, c). According to diffraction analysis data [33], these regions contain fine needle-shaped cementite particles with an average size of 10×25 nm and exhibit a high scalar dislocation density. With decreasing distance to the wheel–rail contact surface, microstructural evolution at the fillet follows trends similar to those observed at the tread surface. Pearlite undergoes intensive destruction, the fragmented structure becomes increasingly refined with a reduction in fragment size, and the ferrite–carbide mixture progressively expands. At the contact surface, this component accounts for approximately 60 % of the material volume. Pearlite (lamellar, destroyed, and globular) remains present, while a subgrain structure appears in a small fraction (approximately 2 %). The evolution of the volume fractions of the morphological components in the fillet region as the contact surface is approached is shown in Fig. 3, d.

As at the tread surface, the dislocation structure within all morphological components consists of either randomly distributed dislocations or dislocation networks. The scalar dislocation density (ρ) increases in all components as the wheel – rail contact surface is approached. The highest values of ρ are observed in the ferrite – carbide mixture (the completely destroyed structure), whereas the lowest values correspond to the subgrain structure. Because, at the contact surface, the ferrite – carbide mixture occupies 60 % of the material volume and the subgrain structure only 2 %, the average scalar dislocation density of the material is governed primarily by the ferrite – carbide mixture. As a result, unlike the tread surface, the average value of ρ increases toward the contact surface (Fig. 3, f). The curvature – torsion of the α-phase crystal lattice also increases toward the contact surface. Accordingly, the excess dislocation density rises at an even higher rate and rapidly approaches the value of ρ (Fig. 3, f). This behavior is attributed to the appearance of an elastic component in lattice bending – torsion within the ferrite – carbide mixture, fragmented lamellar pearlite, and subgrain structure. As a consequence, the amplitude of the long-range internal stresses σis exceeds the shear stress σF (Fig. 3, h), with the elastic component of σis dominating over the plastic component, as also observed at the tread surface.

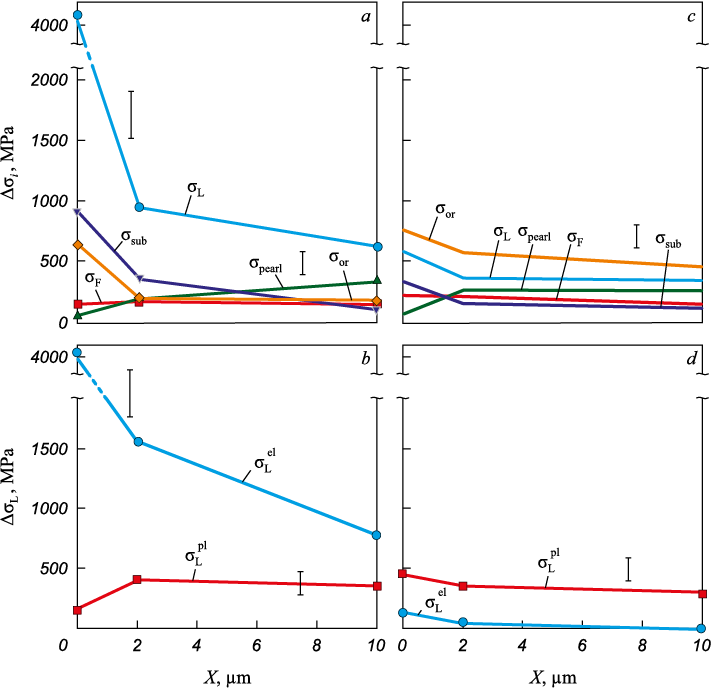

Using the obtained quantitative fine structure parameters, the principal strengthening mechanisms of hypereutectoid rail steel were analyzed and compared at different distances from the contact surface after long-term operation, both along the central axis of symmetry of the rail head (the tread surface) and along the radius of rounding of the rail head (the fillet). The following contributions were considered: strengthening due to pearlite Δσpearl (barrier braking within pearlite colonies); strengthening by incoherent cementite particles Δσor (Orowan bypass mechanism); strengthening by grain boundaries and subboundaries Δσsub (substructural strengthening associated with intraphase boundaries); strengthening by the dislocation substructure ΔσF (forest dislocation strengthening, i.e., internal shear stress); and strengthening by internal stress fields ΔσL (long-range stress-field strengthening). Quantitative evaluation of these contributions was performed using the relationships given in [33 – 36]. The results are summarized in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Contributions of the main strengthening mechanisms ∆σi to yield strength of E90KhAF steel |

The analysis shows that, irrespective of the sampling direction, the strength of the rail metal is governed by the distance from the wheel – rail contact surface (Fig. 3). As the contact surface is approached, all major strength characteristics increase, with the most pronounced strengthening confined to a near-surface layer no thicker than 2 mm. At greater depths, the strength properties of the steel remain close to those of the initial-state steel. Along the tread surface, strengthening is dominated by internal long-range (local) stresses, primarily of an elastic nature, together with substructural strengthening and strengthening by incoherent particles. This reflects the fact that, at the contact surface, the subgrain structure occupies nearly the entire material volume (90 %). The nanometer-scale size of the subgrains (approximately 80 nm) results in a high density of subboundaries and junctions, predominantly triple junctions, which act as sources of bending extinction contours. These are mainly elastic in nature and give rise to high long-range internal stresses, whose elastic component exceeds the plastic component by more than an order of magnitude.

At the contact surface of the fillet, strengthening is governed primarily by incoherent particles, together with contributions from internal long-range (local) stresses and internal shear stresses associated with forest dislocations. This behavior arises because the main morphological components controlling strengthening are the ferrite–carbide mixture, which occupies 60 % of the material volume and has a low boundary density, and fragmented lamellar pearlite, accounting for 20 %. Although the subgrain structure formed at the contact surface increases the number of grain junctions and, consequently, the contribution of ΔσL , its overall effect on strengthening remains limited because of its small volume fraction (2 %).

Conclusions

A quantitative assessment of the fine structure and strengthening mechanisms of hypereutectoid rail steel was performed for individual morphological components and for the material overall at various distances from the wheel – rail contact surface, considering both the tread surface (along the central axis of symmetry of the rail head) and the fillet (along the radius of rounding of the rail head), after a passed tonnage of 187 million tons (gross).

A clear microstructural contrast was observed depending on where the gradient-affected layers develop within the rail head – at the tread surface versus the fillet. Near the wheel – rail contact surface, the tread surface is dominated by a subgrain structure, whereas the fillet is characterized primarily by a ferrite – carbide mixture. This difference leads to distinct prevailing strengthening mechanisms: at the tread surface, strengthening is governed mainly by internal stress fields, while at the fillet it is driven predominantly by incoherent particles.

Regardless of the sampling direction, the strength of the rail metal varies systematically with distance from the wheel – rail contact surface. The strongest strengthening response is confined to the near-surface layer no thicker than 2 mm. Deeper into the rail head, the steel largely retains strength levels comparable to those of the initial state steel.

References

1. Shur E.A. Rail Damage. Moscow: Intekst; 2012:192. (In Russ.).

2. Steenbergen M. Rolling contact fatigue: Spalling versus transverse fracture of rails. Wear. 2017;380-381:96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2017.03.003

3. Skrypnyk R., Ekh M., Nielsen J.C.O., Palsson B.A. Prediction of plastic deformation and wear in railway crossings – Comparing the performance of two rail steel grades. Wear. 2019;428-429:302–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2019.03.019

4. Miranda R.S., Rezende A.B., Fonseca S.T., Fernandes F.M., Sinatora A., Mei P.R. Fatigue and wear behavior of pearlitic and bainitic microstructures with the same chemical composition and hardness using twin-disc tests. Wear. 2022; 494-495:204253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2022.204253

5. Pereira H.B., Alves L.H.D., Rezende A.B., Mei P.R., Goldenstein H. Influence of the microstructure on the rolling contact fatigue of rail steel: Spheroidized pearlite and fully pearlitic microstructure analysis. Wear. 2022;498-499:204299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2022.204299

6. Lojkowski W., Djahanbakhsh M., Bürkle G., Gierlotka S., Zielinski W., Fecht H.-J. Nanostructure formation on the surface of railway tracks. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2001;303(1-2):197–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-5093(00)01947-X

7. Ivanisenko Yu., Fecht H.-J. Microstructure modification in the surface layers of railway rails and wheels: Effect of high strain rate deformation. Steel Tech. 2008;3(1):19–23.

8. Takahashi J., Kawakami K., Ueda M. Atom probe tomography analysis of the white etching layer in a rail track surface. Acta Materialia. 2010;58(10):3602–3612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2010.02.030

9. Dylewski B., Bouvier S., Risbet M. Multiscale characterization of head check initiation on rails under rolling contact fatigue: Mechanical and microstructure analysis. Wear. 2016;366-367:383–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2016.06.019

10. Dylewski B., Risbet M., Bouvier S. The tridimensional gradient of microstructure in worn rails – Experimental characterization of plastic deformation accumulated by RCF. Wear. 2017;392-393:50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2017.09.001

11. Chen H., Ji Y., Zhang C., Liu W., Chen H., Yang Z., Chen L.-Q., Chen L. Understanding cementite dissolution in pearlitic steels subjected to rolling-sliding contact loading: A combined experimental and theoretical study. Acta Materialia. 2017;141:193–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2017.09.017

12. Ma L., Guo J., Liu Q.Y., Wang W.J. Fatigue crack growth and damage characteristics of high-speed rail at low ambient temperature. Engineering Failure Analysis. 2017;82: 802–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2017.07.026

13. Al-Juboori A., Zhu H., Li H., McLeod J., Pannila S., Barnes J. Microstructural investigation on a rail fracture failure associated with squat defects. Engineering Failure Analysis. 2023;151:107411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2023.107411

14. Dement’ev V.P., Korneva L.V., Serpiyanov A.I., Chernyak S.S., Pozdeev V.N., Tuzhilina L.V., Fal’ko N.V. High-performance rails for Siberia. Sovremennye tekhnologii. Sistemnyi analiz. Modelirovanie. 2008;(2(18)):102–104. (In Russ.).

15. Prohaska S., Jorg A. Improvement of rail steels. Zheleznye dorogi mira. 2016;(1):74–76. (In Russ.).

16. Dobuzhskaya A.B., Galitsyn G.A., Yunin G.N., Polevoi E.V., Yunusov A.M. Effect of chemical composition, microstructure and mechanical properties on the wear resistance of rail steel. Steel in Translation. 2020;50(12):906–910. https://doi.org/10.3103/S0967091220120037

17. Wen J., Marteau J., Bouvier S., Risbet M., Cristofari F., Secorde P. Comparison of microstructure changes induced in two pearlitic rail steels subjected to a full-scale wheel/rail contact rig test. Wear. 2020;456-457:203354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2020.203354

18. Hu Y., Guo L.C., Maiorino M., Liu J.P., Ding H.H., Lewis R., Meli E., Rindi A., Liu Q.Y., Wang W.J. Comparison of wear and rolling contact fatigue behaviours of bainitic and pearlitic rails under various rolling-sliding conditions. Wear. 2020;460-461:203455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2020.203455

19. Hu Y., Zhou L., Ding H.H., Lewis R., Liu Q.Y., Guo J., Wang W.J. Microstructure evolution of railway pearlitic wheel steels under rolling-sliding contact loading. Tribology International. 2021;154:106685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2020.106685

20. Zhou L., Bai W., Han Z., Wang W., Hu Yu., Ding H., Lewis R., Meli E., Liu Q., Guo J. Comparison of the damage and microstructure evolution of eutectoid and hypereutectoid rail steels under a rolling-sliding contact. Wear. 2022;492-493:204233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2021.204233

21. Bai W., Zhou L., Wang P., Hu Y., Wang W., Ding H., Han Z., Xu X., Zhu M. Damage behavior of heavy-haul rail steels used from the mild conditions to harsh conditions. Wear. 2022;496-497:204290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2022.204290

22. Chernyak S.S., Broido V.L., Tuzhilina L.V. The development of the composition and manufacturing technology of the wear resistant rails made of hypereutectoid steel. Modern technologies. System analysis. Modeling. 2017; 56(4):197–206. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.26731/1813-9108.2017.4(56).197-206

23. Kormyshev V.E., Yuriev A.A., Rubannikova Yu.A., Aksenova K.V. Distribution of structure-phase states along the rail head cross-section during their long-term performance. Bulletin of the Siberian State Industrial University. 2020;(4): 20–24. (In Russ.).

24. Lukovnikov D.N. Production of hundred-meter rails. Sovremennye innovatsii. 2021;(2(40)):13–15. (In Russ.).

25. Alwahdi F.A.M., Kapoor A., Franklin F.J. Subsurface microstructural analysis and mechanical properties of pearlitic rail steels in service. Wear. 2013;302(1-2):1453–1460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2012.12.058

26. Wang W.J., Lewis R., Yang B., Guo L.C., Liu Q.Y., Zhu M.H. Wear and damage transitions of wheel and rail materials under various contact conditions. Wear. 2016;362-363: 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2016.05.021

27. Pan R., Ren R., Zhao X., Chen C. Influence of microstructure evolution during the sliding wear of CL65 steel. Wear. 2018;400-401:169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2018.01.005

28. Pan R., Chen Yu., Lan H., Shiju E., Ren R. Investigation into the microstructure evolution and damage on rail at curved tracks. Wear. 2022;504-505:204420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2022.204420

29. Nguyen B.H., Al-Juboori A., Zhu H., Zhu Q., Li H., Tieu K. Formation mechanism and evolution of white etching layers on different rail grades. International Journal of Fatigue. 2022;163:107100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2022.107100

30. Mojumder S., Mishra K., Singh K., Qiu C., Mutton P., Singh A. Effect of track curvature on the microstructure evolution and cracking in the longitudinal section of lower gauge corner flow lips formed in rails. Engineering Failure Analysis. 2022;135:106177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106117

31. Gromov V.E., Yuriev A.B., Morozov K.V., Ivanov Yu.F. Microstructure of Quenched Rails. Cambridge: ISP Ltd.; 2016:157.

32. Grigorovich K.V., Gromov V.E., Kuznetsov R.V., Ivanov Yu.F., Shliarova Yu.A. Formation of a thin structure of pearlite steel under ultra-long plastic deformation. Doklady Physics. 2022;67(4):119–122. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1028335822040048

33. Porfiriev M.A. Gromov V.E., Ivanov Yu.F., Popova N.A., Shlyarov V.V. Thin Structure of Long-Length Rails Made of Transeutectoid Steel after Long-Term Operation. Novokuznetsk: Poligrafist; 2023:285. (In Russ.).

34. Popova N.A., Gromov V.E., Ivanov Yu.F., Porfiryev M.A., Nikonenko E.L., Shlyarova Yu.A. Effect of long-term operation on structural-phase state of hypereutectoid rail steel. Inorganic Materials: Applied Research. 2024;15(4):968-977. https://doi.org/10.1134/S2075113324700473

35. Gol’dstein M.I., Farber V.M. Dispersion Hardening of Steel. Moscow: Metallurgiya; 1979:208. (In Russ.).

36. Popova N.A., Gromov V.E., Nikonenko E.L., Ivanov Yu.F., Porfiriev M.A., Shlyarov V.V., Kryukov R.E. Assessment of hardening mechanisms forming the yield strength in hypereutectoid steel. Izvestiya vuzov. Fizika. 2024;67(2(795)): 70–82. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17223/00213411/67/2/8

About the Authors

N. A. PopovaRussian Federation

Natal’ya A. Popova, Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Senior Researcher of the Scientific and Educational Laboratory “Nanomaterials and Nanotechnologies”, Tomsk State University of Architecture and Building

42 Kirova Str., Novokuznetsk, Kemerovo Region – Kuzbass 654007, Russian Federation

2 Solyanaya Sqr., Tomsk 634003, Russian Federation

V. E. Gromov

Russian Federation

Viktor E. Gromov, Dr. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Prof., Head of the Chair of Science named after V.M. Finkel’

42 Kirova Str., Novokuznetsk, Kemerovo Region – Kuzbass 654007, Russian Federation

A. B. Yur’ev

Russian Federation

Aleksei B. Yur’ev, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Prof., Rector

42 Kirova Str., Novokuznetsk, Kemerovo Region – Kuzbass 654007, Russian Federation

E. L. Nikonenko

Russian Federation

Elena L. Nikonenko, Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Assist. Prof. of Chair of Physics

2 Solyanaya Sqr., Tomsk 634003, Russian Federation

M. A. Porfir’ev

Russian Federation

Mikhail A. Porfir’ev, Research Associate of Department of Scientific Researches

42 Kirova Str., Novokuznetsk, Kemerovo Region – Kuzbass 654007, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Popova N.A., Gromov V.E., Yur’ev A.B., Nikonenko E.L., Porfir’ev M.A. Hardening of surface layers of long rail head during long-term operation. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):572-580. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-572-580