Scroll to:

Strength characteristics of investment patterns obtained by compaction of waxy material powders in the field of centrifugal forces

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-563-571

Abstract

The use of investment casting process is aimed at producing castings of complex configuration with increased dimensional and geometric accuracy from a wide range of casting steels and non-ferrous alloys. A number of operations during the implementation of such a process are accompanied by the appearance of defects of a thermophysical nature (shrinkage of the pattern material and its thermal expansion during melting, leading to a violation of the ceramic mold integrity), which, to a certain extent, prevents the expansion of the casting nomenclature. The formation of experimental porous investment patterns by compaction of powders of waxy materials is aimed at eliminating such defects, but, due to the lack of information on the processes accompanying the compaction of waxy powders (in some cases manifested in the elastic response of the material or a change in the strength characteristics of the compacts), requires separate study. It was previously established that the distribution of density values in a paraffin powder compact is provided by directional loading of the compacted material, including in the field of centrifugal forces, which allows obtaining the surface configuration of a body of revolution with a predictable distribution of properties in each of its sections. In this paper, using the example of forming a section of a body of revolution, a comparison is given of the calculated and experimental dependencies of the relative density of compacts (obtained from different fractions of the PS50/50 material) on the stresses arising during their compaction in the field of centrifugal forces, as well as the average values of the density of compacts on the molds rotation speed. Pictures of the stress-strain state of compacts are presented when determining the values of their compressive strength characteristic of various waxy materials. The results of the experiment are aimed at solving the problems of increasing the efficiency of processes for obtaining investment patterns, the configuration of which is a body of revolution, formed by compaction of powdered waxy materials in the field of centrifugal forces.

Keywords

For citations:

Bogdanova N.A., Zhilin S.G., Predein V.V. Strength characteristics of investment patterns obtained by compaction of waxy material powders in the field of centrifugal forces. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):563-571. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-563-571

Introduction

Improving the efficiency of producing accurate billets from a wide range of ferrous and non-ferrous alloys by investment casting requires the development and modernization of technological processes that eliminate machining operations and expand the range of cast products for the aircraft, shipbuilding, and mechanical engineering industries. The manufacture of castings of complex spatial configuration [2; 3], characterized by high dimensional and geometric accuracy and low surface roughness, is predominantly carried out by investment casting [4 – 6].

The general sequence of traditional operations in the investment casting process involves the formation of investment patterns, their assembly into pattern clusters, sequential coating and drying of ceramic shell layers, melting out the pattern material from the ceramic mold, firing of the shell in a supporting filler, and pouring the shell mold with liquid metal followed by machining of the cast billets [7 – 9].

Throughout the investment casting process, the technological stages mentioned above are accompanied by thermophysical phenomena that can lead to geometric distortion of the investment pattern due to shrinkage [10 – 13], deformation, and fracture of ceramic shell mold sections caused by thermal expansion of pattern materials both during dewaxing and at the stages of firing and metal pouring [14 – 17].

The traditional approach to improving the thermostability of investment patterns has been to select pattern material components with low thermal expansion [18], while increasing the crack resistance of ceramic molds is mainly achieved by using reinforcing elements or new binding agents [19; 20].

A promising way to address the complex of thermophysical problems is the use of porous investment patterns formed by compaction of fractions of waxy materials. Such investment patterns do not have shrinkage defects and do not exert expanding effects on ceramic molds [21]. A series of experiments has provided practical data on the stress–strain behavior of waxy materials, aimed at eliminating the elastic relaxation of compacts (whose magnitude is an order of magnitude smaller than the shrinkage value and amounts to about 1 % of the compact volume) formed during their compaction [22].

Greater control over the porosity of investment patterns can be achieved by compaction of powders of waxy materials in the field of centrifugal forces, which provides directional loading of the powder compact during compaction [23]. Compaction of powders of waxy materials makes it possible to obtain an investment pattern in the form of bodies of revolution, the configuration of the external surface of which is determined by the rotating mold. However, achieving a uniform distribution of properties within such compacts requires a substantially more complex mold design, whereas producing a body-of-revolution investment pattern by pressing a pasty pattern compound may lead to shrinkage defects upon cooling. Research in this area is motivated by the need to identify an energy-efficient compaction mode for forming compacts in the shape of bodies of revolution in the field of centrifugal forces, allowing the mold rotation speed to be reduced while maintaining acceptable strength of compacts made of various waxy materials.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine the force parameters of the process of compaction in the field of centrifugal forces for fractions of powdered waxy pattern material PS 50/50 and to analyze the strength characteristics of such compacts in comparison with those obtained by compaction in a closed mold, including those produced from paraffin grade Т1.

To achieve these objectives, the following tasks were se the study addressed the following tasks:

– selecting a computational method to obtain the stress dependencies (derived using the formulas of M. Yu. Balshin and G. N. Zhdanovich) arising during vertical uniaxial compaction of PS 50/50 powder compacts with particle sizes of 2.5 and 0.63 mm in the relative density range 0.8 – 1.0, best corresponding to the experimental data, and comparing the adapted calculated data with experimental results;

– comparing the calculated and experimental mold rotation speeds required to achieve average compact densities in the range 842 – 935 kg/m3 (corresponding to load-bearing capacity) for PS 50/50 fractions 2.5 and 0.63 mm;

– comparing the strength characteristics of compacts made of waxy powdered materials grades T1 and PS 50/50 obtained by uniaxial vertical compaction and compaction in the field of centrifugal forces.

Methods

The waxy powder selected for this study was PS 50/50, the most widely used pattern material in investment casting. Particle size fractions of 0.63 and 2.5 mm were used, as these sizes are technologically convenient and ensure homogeneous compacts [24]. The fractions were obtained by sieving on model 026 sieves manufactured in accordance with GOST 29234.3–91 “Foundry sands. Method for determination of mean grain size and uniformity coefficient”. PS 50/50 is an alloy of equal mass fractions of paraffin and stearin and belongs to the first classification group of pattern materials [25]. As a reference material, paraffin grade T1 was used; its properties are regulated by GOST 23683–89 “Petroleum solid paraffins. Specifications”. The strength characteristics of compacts obtained from PS 50/50 were compared with those of compacts made from T1. Data on the average densities of compacts formed in the field of centrifugal forces at different mold rotation speeds were taken from the authors’ previous work [23]. The densities ρ of the materials in the experiment, corresponding to their cast state, were: PS 50/50 – ρ = 935 kg/m3, T1 – ρ = 860 kg/m3.

Earlier experiments refined the permissible porosity (P) range of 0 % ≤ P ≤ 10 %, within which waxy compacts produced by uniaxial compaction of materials T1 and PS 50/50 retain their service strength [21]. Porosity was calculated as

| \[\Pi = \left( {1 - \frac{{{\rho _{\rm{comp}}}}}{{{\rho _{\rm{cast}}}}}} \right) \cdot 100{\rm{ }}\% ,\] | (1) |

where ρcomp is the density of the compacted sample, kg/m3; ρcast is the density of the cast material, kg/m3.

Thus, the density ranges ensuring satisfactory performance were 774 – 860 kg/m3 for T1 and 842 – 935 kg/m3 for PS 50/50.

Before placing a measured portion of the powdered pattern material into the mold, the inner surface of the mold was treated with kerosene to reduce friction between the compacted material and the wall. Uniform distribution of the powder within the mold prior to compaction was achieved by vibrating the mold on a vibrating table at 3.5 Hz for 5 min.

The compaction of waxy material powders in the field of centrifugal forces makes it possible to obtain investment patterns in the form of bodies of revolution, with the outer surface geometry defined by the shaping surface of the rotating mold. In this case, centrifugal forces generate an almost uniform pressure distribution throughout the compact from the center of rotation to the periphery, which results in a nearly uniform distribution of properties; in particular, the density is essentially the same at equal radial distances from the rotation axis.

Producing a compact in the form of a body of revolution imposes specific requirements on the equipment due to the high mold rotation speeds traditionally required (6,000 – 15,000 rpm), which is energy-inefficient [26].

Preliminary studies showed that the use of an attached mass acting as a punch is a feasible way to form compacts in the shape of bodies of revolution in the field of centrifugal forces. In this scheme, the compaction process includes the following steps:

– a measured portion of the powdered pattern material is placed into a mold mounted on the centrifuge shaft. The mold defines the geometry of the compact and is rotated at a speed sufficient to form a cavity at the center of the compact;

– a flat spiral spring containing the attached mass (for example, steel balls) is inserted into this cavity. The mold is then spun again, and the elements of the attached mass self-distribute along the inner surface of the steel spring.

Experiments showed that, for PS 50/50, this compaction scheme requires a mold rotation speed in the range of 3500 – 4000 rpm.

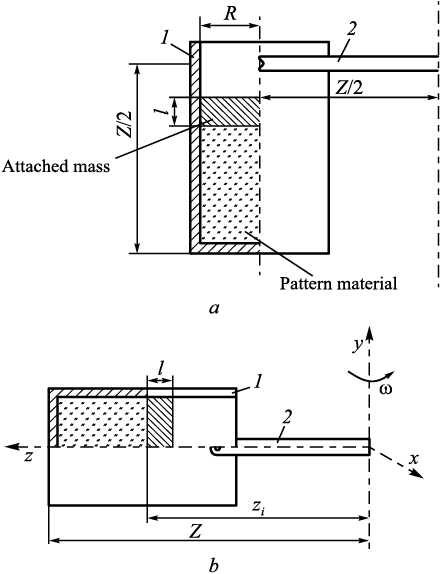

This design provides the necessary pressure directed from the centrifuge rotor axis toward the periphery at acceptable rotation speeds [23]. In the experiments, the attached mass was a washer made of steel 45 with a mass of 0.125 kg, radius R = 0.023 m, and height l = 0.1 m (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Scheme of forming a compact from powder material |

To simplify the calculation of the parameters of the body-of-revolution forming process, the scheme shown in Fig. 1 was used. In Fig. 1, a, the schematic diagram shows compaction of powdered waxy pattern material in a mold (1) shaped as a cup of radius R, fixed to the centrifuge rotor holder (2) and at rest. In Fig. 1, b, the compaction stage corresponds to rotation of the centrifuge rotor at ω = 3500 – 4000 rpm, when the z axis of the holder coincides with the mold axis. The coordinate z varies from z0 to zi and characterizes the movement of the powder surface during compaction, while Z is the distance from the rotor axis to the bottom of the cylindrical mold (Z = 0.015 m). To relieve stresses in the compacted powder and reduce the elastic response of the compact, the mold was rotated at angular velocity ω for 7 min.

During centrifugal compaction, the centrifuge rotor speed was continuously recorded. After compaction, the compacts were removed from the molds and their densities measured. The specimens were then subjected to compressive loading until fracture at a crosshead speed of 22 mm/min, which complies with GOST 4651–2014 “Plastics. Compression test method”. Experimental fracture data for compacts from PS 50/50 were compared with those obtained for compacts from T1. The stresses arising during loading were recorded using a Shimadzu AG-X plus testing machine.

Based on the computational and experimental results, the following relationships were obtained:

– comparison of calculated (according to the equations of M.Yu. Balshin and G.N. Zhdanovich) and experimental dependences of load on relative density for samples formed from 0.63 and 2.5 mm fractions;

– comparison of calculated and experimental average densities of compacts obtained from 0.63 and 2.5 mm fractions as a function of mold rotation speed;

– stress–strain relationships recorded during compressive loading of samples made of PS 50/50 and T1 materials produced by uniaxial pressing and by compaction in the field of centrifugal forces.

Results and discussion

The schematic diagram in Fig. 1, similar to that proposed in [27], is presented in Cartesian coordinates x, y, and z to enable numerical analysis of the compact formation process in a rotating cylindrical mold and to predict the property distribution within the compact. In this scheme, the z axis coincides with the cylinder axis, and the coordinate origin is located on the centrifuge rotor axis y.

The centrifugal force compacting the material is expressed as

| \[\vec F = m\vec \omega (\vec r\vec \omega ).\] | (2) |

The force vector has two nonzero components

| \[{F_x} = m{r_x}{\omega ^2},{\rm{ }}{F_z} = m{r_z}{\omega ^2}.\] | (3) |

Under the action of the force \(\vec F\), the Fz component causes the compacted powder material to move toward the bottom of the cylindrical mold, whereas the Fx component promotes material spreading from the mold center toward the walls along the x axis. The effect of Fx is small, and together with the friction force it can be neglected by setting both to zero, which simplifies the calculations. In this formulation, the centrifugal force depends only on the z coordinate, and the compaction process can be treated as layer-by-layer densification of a powder compact represented by n layers, each of height \(h_i^j\) (where i = 1, ..., n is the layer number, and j is the iteration number in the calculation process). The calculation starts from the upper layer (z = z0 ) and proceed down to the layer adjacent to the mold bottom (z = Z). At the initial iteration (j = 0), all layer heights are equal

| \[h_i^0 = \frac{{Z - {z_0}}}{n} = \frac{H}{n}.\] | (4) |

The mass m can be expressed in terms of density as m = ρV = ρHS, where V is the compact volume, Н is the compact height, and S is the cross-sectional area of the mold. Dividing the centrifugal force component Fz , which generates pressure, by the cross-sectional area S = πR2 gives the stress in the i-th layer of the powder compact:

| \[\sigma _i^j = \sum\limits_{l = 1}^i {\rho _l^jh_l^jz_l^j{\omega ^2}} ,{\rm{ }}z_i^j = Z - \sum\limits_{l = n}^{i + 1} {h_i^j} .\] | (5) |

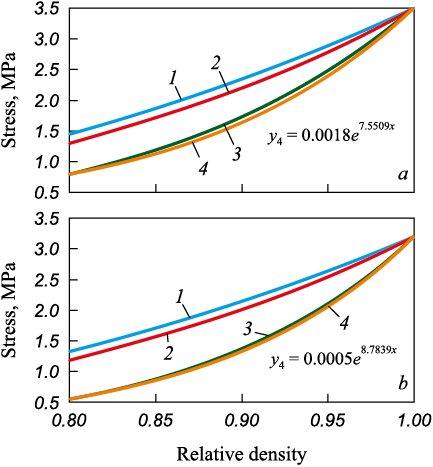

Since the density \(\rho _l^j\) depends on the stress \(\sigma _{i - 1}^j\), the calculation is carried out in two stages. First, the stress at the current iteration j is determined from the densities obtained at the previous iteration (j = 1). Then, the densities of each layer are recalculated until the difference between successive iterations becomes negligibly small. For this, a known functional dependence between the density of the material and the pressing stress ρ = ρ(σ), is required. Fig. 2 presents the results of a series of preliminary experiments to determine the stresses arising during uniaxial vertical compaction of PS 50/50 powder fractions of 2.5 mm (Fig. 2, a) and 0.63 mm (Fig. 2, b) to relative densities within the range 0.8 – 1.0. Curves 1 and 2 in Fig. 2 show the calculated results based on the equations proposed by M.Yu. Balshin (Eq. (6)) and G.N. Zhdanovich (Eq. (7)) for describing the compaction behavior of powdered bodies [28; 29]:

| \[\sigma = {\sigma _{\max }}{\theta ^m},{\rm{ }}m = 2 + \frac{\theta }{{\theta - {\theta _0}}};\] | (6) |

| \[\sigma = {\sigma _{\max }}\frac{{{\theta ^m} - \theta _0^m}}{{1 - \theta _0^m}},{\rm{ }}m = 1 + \frac{2}{{1 - {\theta _0}}},\] | (7) |

where σmax is the stress at which the density ρ reaches the cast density ρmax ; θ = ρ/ρmax is the relative density; θ0 = ρ0 /ρmax is the initial relative bulk density, and ρ0 is bulk density of the loose powder.

Fig. 2. Calculated and experimental dependences |

As can be seen from Fig. 2, the stresses during compaction of the powder compact made from the 0.63 mm fraction are slightly lower than those for the 2.5 mm fraction.

Since the curve 2 obtained according to the Zhdanovich equation lies closer to the experimental exponential trend (curve 4), the original data were approximated by adjusting the exponent m for the best fit. The exponents m for the PS 50/50 material fractions were found to be 7.55 and 8.78, respectively.

The inverse dependence of relative density on stress, corresponding to Eq. (7), can be written as:

| \[\rho = {\rho _{\max }}\theta = {\rho _{\max }}{\left[ {\frac{\sigma }{{{\sigma _{\max }}}}\left( {1 - \theta _0^m} \right) + \theta _0^m} \right]^{1/m}}.\] | (8) |

Using Eqs. (5) and (8), the density distribution in the powder compact along the height of the cylindrical mold can be determined for a given angular velocity ω. To reduce the angular velocity ω from 6,000 – 15,000 rpm to acceptable levels, an attached mass is placed on the surface of the compacted material. Its presence increases the uniformity of density distribution within the compact by exerting additional pressure on it.

For this purpose, by integrating the Fz component in Eq. (3) for a material with a uniform density distribution throughout its volume, the stress provided by the attached mass can be obtained. Dividing σ by the mold cross-sectional area S yields the value of the stress acting on the surface of the compacted material (z = z0 ) as a result of the influence of the attached mass:

| \[{\sigma _{{\rm{add}}}} = \frac{{{m_{{\rm{add}}}}}}{S}\left( {{z_0} - \frac{1}{2}l} \right){\omega ^2},\] | (9) |

where madd is the attached mass, l is the thickness of the attached mass made in the form of a washer. As compaction proceeds, the interface between the powder surface and the attached mass shifts from the mold center toward the periphery (z = Z).

Accordingly, for a given angular velocity, the stresses in the compact can be calculated from Eqs. (5) and (9), and the corresponding average compact densities can then be obtained using the adapted Zhdanovich equation.

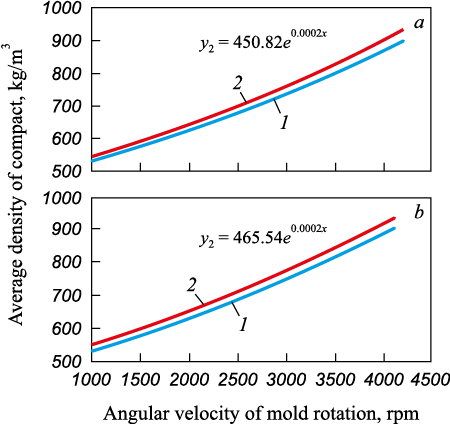

For the PS 50/50 material, the angular velocity of the mold at which the average density of compacts corresponds to the required range of 842 – 935 kg/m3 was determined. Fig. 3 shows the graphical dependences of the average density of compacts formed from PS 50/50 with particle sizes of 2.5 mm (Fig. 3, a) and 0.63 mm (Fig. 3, b) on the mold rotation speed. The calculated curves (1) lie slightly below the experimental exponential curves (2) in both cases. The experiment showed that a density of 935 kg/m3, corresponding to the cast state of the compact formed from the 0.63 mm fraction, is achieved at an angular velocity of 4050 rpm. For compacts produced from the 2.5 mm fraction, achieving the same density required a slightly higher velocity – approximately 4200 rpm. Overall, the use of an attached mass significantly reduced the necessary mold rotation speed to a range of 3500 – 4200 rpm.

Fig. 3. Dependences of the average density of compacts made of PS50/50 material |

If the density distribution in compacts produced by direct uniaxial vertical compaction and by compaction in the field of centrifugal forces differ, corresponding differences will also be expected in their behavior under uniaxial compression to failure. It is evident that the intrinsic properties of the materials (T1 and PS 50/50) will partly account for the observed differences in the compressive strength of the compacts.

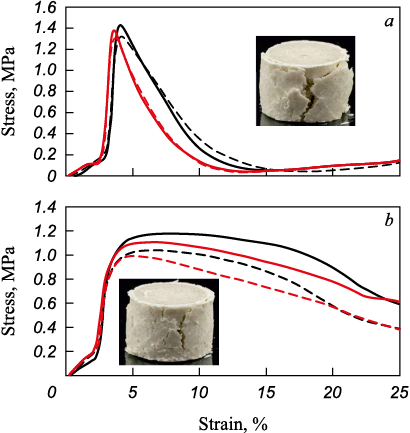

Fig. 4 compares the stress–strain relationships for cylindrical compacts with porosity P = 0 % obtained by direct pressing in a closed die (at a punch travel rate of 0.5 mm/s) and by compaction in the field of centrifugal forces. Black curves represent samples produced by direct pressing of waxy powders in a closed cylindrical mold; red curves correspond to samples obtained by centrifugal compaction. Solid lines denote compacts made from 2.5 mm fractions; dashed lines correspond to 0.63 mm fractions.

Fig. 4. Dependence of stress on deformation under vertical uniaxial compressive |

Visual analysis of the “stress–strain” curves for samples made of T1 (Fig. 4, a) and PS 50/50 (Fig. 4, b) reveals notable differences in their deformation behavior under compressive loading. The photographs included in Fig. 4 show that T1 material (melting point ≈ 60 °С [21]) deforms in a brittle manner, whereas PS 50/50 material (melting point ≈ 52 °C) exhibits greater plasticity. Overall, the resistance to compressive loading of compacts formed from T1 powder is slightly higher than that of compacts produced from PS 50/50, which, in all likelihood, can also be explained by the greater plasticity of the latter. It should be noted that a common feature characterizing all variants of experimental compacts is the dominance of the peak compressive stress values obtained during strength testing of samples made from the 2.5 mm fraction over the strength values of samples made from the smaller fraction – on average by 7 % for the case of single-action uniaxial compaction and by 12 % for compaction in the field of centrifugal forces.

Analysis of the relationships presented in Fig. 4 also showed that the compressive strength of samples formed in the field of centrifugal forces is, on average, 15 % lower than that of compacts obtained by single-action compaction, which, however, is sufficient to ensure their further technological applicability.

Conclusions

As a result of a series of computational and experimental studies, the force parameters of the compaction process under centrifugal forces were determined for powdered bodies made from fractions of the waxy pattern material PS 50/50. A comparative analysis was performed of the compressive strength values of cylindrical compacts and those of samples obtained by compaction of paraffin grade T1 in a closed mold.

The calculation method proposed by G.N. Zhdanovich, adapted to determine the stress relationships arising during vertical uniaxial compaction of PS 50/50 powder compacts in the technologically acceptable range of relative densities (0.8 – 1.0), was found to be the most suitable.

The experimental results showed that density values corresponding to compacts with porosity of 0 % ≤ P ≤ 10 %, formed from PS 50/50 fractions using an attached mass, are achieved at mold rotation speeds ranging from 3500 to 4200 rpm. The points on the calculated dependences of the average density of PS 50/50 compacts on the mold rotation speed were found to be, on average, 5 % lower than the experimental data, which may be attributed to the neglect of frictional forces between the compacted material and the mold walls in the calculations.

Analysis of the experimental data also established that the compressive strength of samples formed under centrifugal forces is, on average, 15 % lower than that of compacts obtained by single-action compaction, which, however, remains sufficient to ensure their further technological use.

References

1. Yuan G., Li Y., Hu L., Fu W. Preparation of shaped aluminum foam parts by investment casting. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2023;314:117897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2023.117897

2. Kapranos P., Carney C., Pola A., Jolly M. Advanced casting methodologies: Investment casting, centrifugal casting, squeeze casting, metal spinning, and batch casting. Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering. Comprehensive Materials Processing. 2014;5:39–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-096532-1.00539-2

3. Singh S., Prakash C., Ramakrishna S. Three-dimensional printing assisted investment casting processes for intricate products. Encyclopedia of Materials: Plastics and Polymers. 2022;1:611–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820352-1.00021-3

4. Huang P.H., Shih L.K.L., Lin H.M., Chu C.I., Chou C.S. Novel approach to investment casting of heat-resistant steel turbine blades for aircraft engines. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2019;104: 2911–2923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-019-04178-z

5. Yusipov R.F., Demyanov E.D., Vinogradov V.Yu., Paremsky I.Ya., Ayrapetyan A.S. Castings size accuracy at investment casting. Liteinoe proizvodstvo. 2021;(9):18–19. (In Russ.).

6. Yarlagadda P.K.D.V., Hock T.S. Statistical analysis on accuracy of wax patterns used in investment casting process. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2003;138(1–3): 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-0136(03)00052-9

7. Pattnaik S., Karunakar D.B., Jha P.K. Developments in investment casting process – A review. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2012;212(11): 2332–2348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2012.06.00

8. Arruebarrena G., Hurtado I., Väinölä J., Cingi C., Dévényi S., Townsend J., Mahmood S., Wendt A., Weiss K., Ben-Dov A. Development of investment-casting process of Mg-alloys for aerospace applications. Advanced Engineering Materials. 2007;9(9):751–756. https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.200700154

9. Odinokov V.I., Evstigneev A.I., Dmitriev E.A., Chernyshova D.V., Evstigneeva A.A. Influence of support filler and structure of shell mold on its crack resistance. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2022;65(4):285–293. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2022-4-285-293

10. Thakre P., Chauhan A.S., Satyanarayana A., Kumar E.R., Pradyumna R. Estimation of shrinkage & distortion in wax injection using Moldex3D simulation. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2018;5(9(3)):19410–19417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2018.06.301

11. Sabau A.S. Alloy shrinkage factors for the investment casting process. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B. 2006; 37:131–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-006-0092-x

12. Dong Y.W., Li X.L., Zhao Q., Yang J., Dao M. Modeling of shrinkage during investment casting of thin-walled hollow turbine blades. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2017;244:190–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2017.01.005

13. Sata A., Ravi B. Bayesian inference-based investment-casting defect analysis system for industrial application. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2017;90(9–12):3301–3315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-016-9614-0

14. Zaslavskaya O.M., Dubrovin V.K., Savin F.M., Nizovtsev N.V. Influence of the model composition on crack formation in investment casting. Tekhnologii metallurgii, mashinostroeniya i materialoobrabotki. 2020;(19):164–170. (In Russ.).

15. Jin S., Liu C., Lai X., Li F., He B. Bayesian network approach for ceramic shell deformation fault diagnosis in the investment casting process. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2017;88:663–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-016-8795-x

16. Behera M.M., Pattnaik S., Sutar M.K. Thermo-mechanical analysis of investment casting ceramic shell: A case study. Measurement. 2019;147:106805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2019.07.033

17. Odinokov V.I., Dmitriev E.A., Evstigneev A.I., Sviridov A.V., Ivankova E.P. Modelling selection of structure and properties of monolayer electrophoretic shell molds during investment casting. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2021;38(4):1672–1676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.08.200

18. Mukhtarkhanov M., Akayev S., Gouda S., Shehab E., Hazrat Ali Md. A novel method for evaluating thermal expansion forces during dewaxing of investment casting and 3D-printing waxes. International Journal of Lightweight Materials and Manufacture. 2024. Available online 17.04.2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlmm.2024.05.004

19. Venkat Y., Choudary K.R., Das D.K., Pandey A.K., Singh S. Ceramic shell moulds for investment casting of low-pressure turbine rotor blisk. Ceramics International. 2021;47(4): 5663–5670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.10.152

20. Kanyo J.E., Schafföner S., Uwanyuze R.S., Leary K.S. An overview of ceramic molds for investment casting of nickel superalloys. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2020;40(15):4955–4973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.07.013

21. Bogdanova N.A., Zhilin S.G. Influence of compression modes of waxy powders on stress-strain state of compacts used in precision casting. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2024;67(5):593–603. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-5-593-603

22. Adamov A.A., Keller I.E., Zhilin S.G., Bogdanova N.A. Identification of the cap model of elastoplasticity of non-compact media under compressive mean stress. Mechanics of Solids. 2024;59(4):1868–1880. https://doi.org/10.1134/S002565442460291X

23. Zhilin S.G., Bogdanova N.A., Firsov S.V., Komarov O.N. Prospects of obtaining removable models by pressing wax-like materials under the influence of centrifugal forces. Metallurgist. 2023;67:814–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11015-023-01567-4

24. Zhilin S.G., Bogdanova N.A., Komarov O.N. Porous wax patterns for high-precision investment casting. Izvestiya. Non-Ferrous Metallurgy. 2023;29(3):54–66. https://doi.org/10.17073/0021-3438-2023-3-54-66

25. Garanin V.F., Ivanov V.N., Kazennov S.A., etc. Investment Casting. Ozerov V.A. ed. Moscow: Mashinostroenie; 1994:448. (In Russ.).

26. Predein V.V., Zhilin S.G., Bogdanova N.A., Komarov O.N. Method for obtaining investment pattern of a body of revolution. Patent RF no 2768654. MPK B22C 7/02, B22D 13/00. Bulleten’ izobretenii. 2022;(9). (In Russ.).

27. Antsiferov V.N., Perel’man G.V. Deflected mode of powder materials formed in centrifuge. Konstruktsii iz kompozitsionnykh materialov. 2012;(4):10–16. (In Russ.).

28. Bal’shin M.Yu. Powder Metallurgy. Moscow: Mashgiz; 1948:286. (In Russ.).

29. Zhdanovich G.M. Theory of Metal Powders Compaction. Moscow: Metallurgiya; 1969:262. (In Russ.).

About the Authors

N. A. BogdanovaRussian Federation

Nina A. Bogdanova, Junior Researcher of the Laboratory of Problems of Creation and Processing of Materials and Products

1 Metallurgov Str., Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk Territory 681005, Russian

Federation

S. G. Zhilin

Russian Federation

Sergei G. Zhilin, Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Assist. Prof., Leading Researcher of the Laboratory of Problems of Creation and Processing of Materials and Products

1 Metallurgov Str., Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk Territory 681005, Russian

Federation

V. V. Predein

Russian Federation

Valerii V. Predein, Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Research Associate of the Laboratory of Problems of Creation and Processing of Materials and Products

1 Metallurgov Str., Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk Territory 681005, Russian

Federation

Review

For citations:

Bogdanova N.A., Zhilin S.G., Predein V.V. Strength characteristics of investment patterns obtained by compaction of waxy material powders in the field of centrifugal forces. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):563-571. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-563-571