Scroll to:

Sub-electrode gap and specific electrical resistance of a ferroalloy furnace bath

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-6-660-664

Abstract

To increase the energy-technological efficiency of a ferroalloy furnace, the author studied the smelting of 45 % ferrosilicon by a carbon-thermal method. In some cases, methods for measuring and changing the specific electrical resistance of charge materials at temperatures up to 1900 K are used to study the technology of smelting ferroalloys for smelting manganese alloys from various ores, carbonaceous ferrochrome, ferrosilicon, ferrosilicon manganese and ferrosilicon aluminum. For a series of heats of 45 % ferrosilicon, measurements of the useful voltage, electrode current, and power factor were carried out. As smelting progressed, the bath resistance was calculated and for the reaction melting zone (melting crucible), the specific electrical resistance in the single-electrode version of the furnace was determined at various sub-electrode gaps. Smelting using technology with an increased sub-electrode gap was performed in a large-scale experimental electric furnace with a capacity of 130 ‒ 290 kV·A. As a result, it was found that an increase in the sub-electrode gap from (0.6 ÷ 0.9) to 6.0 of electrode diameters leads to the effect of a 2.5-fold increase in resistance, voltage and power in the bath (each indicator), but at the same time to a slight decrease in the specific electrical resistance of the melting zone of the furnace with a constant diameter (150 mm) of the electrode. The optimal sub-electrode gap (electrode – substrate distance) in the bath of a single-electrode furnace was determined by changing the specific electrical resistance. The optimal value is 3.33 of the electrode diameter. Assuming deviations of about ±5 % of this value, it is possible to efficiently smelt 45 % ferrosilicon in the range of 3.2 ‒ 3.5 electrode diameters for the sub-electrode gap during the ore recovery process with a closed arc.

Keywords

For citations:

Shkirmontov A.P. Sub-electrode gap and specific electrical resistance of a ferroalloy furnace bath. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2024;67(6):660-664. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-6-660-664

Introduction

The smelting of ferroalloys using the carbon-thermal method is one of the most energy-intensive [1] and material-consuming processes [2] in ferrous metallurgy. The efficiency of a ferroalloy electric furnace depends on numerous factors, including the technological specifics of smelting from ore materials [3; 4]; electrical parameters and operating modes [5; 6]; energy technology parameters, particularly the thermal operation of the ferroalloy furnace bath; and the design features of melting units.

One of the key parameters in ferroalloy production is the sub-electrode gap – the distance between the electrode and the furnace substrate within the furnace bath. For traditional ferroalloy electric furnace designs, when smelting silicon, chromium, and manganese alloys using the carbon-thermal method, the sub-electrode gap typically ranges from approximately 0.6 to 0.9 electrode diameters [7]. Electric furnaces operate in a combined mode of resistance and electric arc, characterized by high electrode current values (tens of kiloamperes) and relatively low voltage, resulting in low active bath resistance.

To enhance energy-technological parameters and enable furnace operation at higher voltages, a smelting technology with an increased sub-electrode gap (exceeding the traditional values of 0.6 ÷ 0.9 electrode diameters) was proposed. This approach improves energy efficiency. By significantly increasing the bath depth, this technology eliminates the need to reduce electrode penetration into the charge while increasing active bath resistance, operating voltage, power factor, and the electrical and thermal efficiency of the furnace [8]. The critical challenge, however, lies in determining the optimal distance to which the electrode–substrate gap can be increased. Increasing this gap also expands the melting zone, including its vertical dimensions within the furnace bath, which necessitates a significant increase in bath depth.

The aim of this study was to smelt 45 % ferrosilicon using the carbon-thermal method and to determine the optimal value for the sub-electrode gap (electrode–substrate distance) in the bath of a single-electrode ferroalloy furnace. The goal was to achieve this without reducing electrode penetration into the charge or negatively affecting the smelting parameters for ferrosilicon. This investigation was conducted using a large-scale experimental electric furnace.

Research method

To study ferroalloy smelting technology, methods for measuring and adjusting the specific electrical resistance of charge materials at temperatures up to 1900 K are commongly applied. These methods have been used for various materials, including manganese alloys derived from Kazakh ores [9], carbonaceous ferrochrome, ferromanganese, 75 % ferrosilicon, ferrosilicomanganese MnSi17 [10], ferrosilicoaluminum [11], chromium alloys [12], and carbonaceous reductants [13]. Most research has concentrated on measuring the specific electrical resistance of non-traditional carbonaceous reductants for ferroalloys [14; 15] and silicon [16; 17].

In the present study, a series of heats was conducted to smelt 45 % ferrosilicon. Measurements were taken for useful voltage, electrode current, and power factor, while bath resistance and the reaction melting zone (melting crucible) were calculated to determine the specific electrical resistance in a single-electrode furnace under various sub-electrode gap conditions.

Before smelting, the furnace bath lining was gradually heated with current applied to coke for at least 24 h. After preheating, the current load was increased, and the first portions of the charge were introduced to initiate smelting with a closed arc. The first tapping of ferrosilicon through the spout occurred no earlier than two hours after the furnace started operating, with a gradual buildup of the burden level achieved by adding small portions of the charge. Subsequent ferrosilicon tappings were performed hourly, accompanied by periodic additions of the charge. Throughout the process, the electrode current (or current density) was maintained within consistent limits, close to the maximum allowable values for the 150 mm diameter graphitized electrode used in the furnace. During stable furnace operation, the working voltage and sub-electrode gap were gradually increased without changing the electrode penetration into the charge between tappings or reducing the ferrosilicon temperature at the furnace outlet [18].

Smelting unit description

The smelting unit was a single-electrode shaft furnace powered by alternating current at a frequency of 50 Hz, supplied to the working graphitized electrode and the electrically conductive carbon substrate. The furnace featured a tapping spout for ferrosilicon, with an electrode diameter of 150 mm and an electrode current of approximately 4.7 kA. The insulating part of the lining was composed of fireclay bricks and granules, while the working layer of the walls was made of chromomagnesite bricks. To enhance durability, the furnace hearth (its lower section) was lined with carbon blocks up to a height of one electrode diameter. The substrate lining consisted of sheet asbestos, fireclay granules, four layers of fireclay bricks, two layers of carbon blocks, and a packing layer of electrode paste. The bath and electrically conductive substrate had a cross-section of 500×500 mm, with a bath depth of 1200 mm. During smelting, the smelting unit operated at a power range of 130 to 290 kV·A [8].

Results and discussion

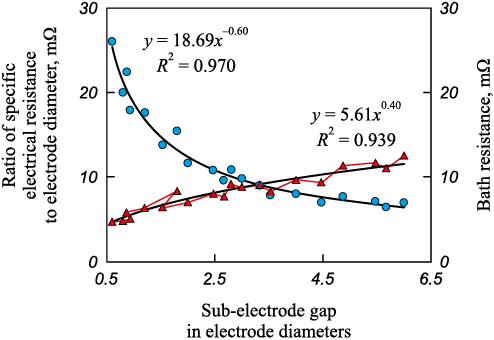

The smelting of 45 % ferrosilicon was conducted using traditional charge materials, including quartzite, coke, and iron turnings. The electrode penetration into the charge was maintained at no less than 1.5 – 1.7 electrode diameters. As a baseline for comparison, the initial smelting was performed with a traditional sub-electrode gap of 0.6 ÷ 0.9 electrode diameters. During prolonged smelting, the electrode–substrate distance was gradually increased by incrementally raising the operating voltage while maintaining a constant electrode current. The maximum sub-electrode gap achieved was 6.0 electrode diameters. The active bath resistance increased from 4.8 to 12 mΩ, representing a 2.5-fold rise. Similarly, furnace power and voltage increased at this electrode–substrate distance without reducing the electrode penetration into the charge, facilitated by the significant increase in the furnace bath depth. Notably, the bath resistance did not change linearly with the increase in the electrode–substrate distance. Consequently, despite the significant rise in bath resistance, a decrease in the specific electrical resistance of the melting zone was observed [19] (see Figure).

Changes in the bath active resistance and specific electrical resistance |

The furnace power factor improved from 0.905 to 0.976, while electrical efficiency increased from 0.904 to 0.942. The relatively low thermal efficiency, typical of small furnaces, increased from 0.309 to 0.374. Specific energy consumption was reduced from 9020 to 7168 kW·h/ton due to the introduction of additional power into the furnace bath. Over the entire smelting campaign, silicon recovery into the alloy ranged from 91.9 – 92.1 %, with the tapping temperature of the alloy between 1650 and 1720 °C. The silicon content in the resulting alloy was 42.3 – 45.6 % Si, fully meeting the standard requirements.

Based on the studies of bath resistance and the specific electrical resistance of the melting zone as influenced by the sub-electrode gap during smelting in a ferroalloy furnace, the following relationships were derived:

| R = 5.61(h/de )0.40; | (1) |

| ρ/de = 18.69(h/de )–0.60, | (2) |

where R is the resistance of the furnace bath; h/de is the sub-electrode gap, expressed in electrode diameters; ρ/de is the ratio of the specific electrical resistance of the melting zone to the electrode diameter.

Despite the significant increase in bath resistance observed during the smelting of 45 % ferrosilicon, a notable decrease in the specific electrical resistance of the furnace melting zone was recorded as the sub-electrode gap (electrode–substrate distance) increased from 0.6 ÷ 0.9 to 6.0 electrode diameters (see Figure).

According to monographs by B.M. Strunsky [20; 21], which consolidate findings by P.V. Sergeev [22], W.H. Kelly, M.J. Morkramer, and other researchers on ferroalloy smelting in electric furnaces, the specific electrical resistance of various alloys spans the following ranges:

– 0.60 ÷ 0.95 Ω·cm for 45 % ferrosilicon;

– 0.50 ÷ 1.25 Ω·cm for 75 % ferrosilicon;

– 0 ÷ 2.00 Ω·cm for high carbon ferrochrome;

– 0.20 ÷ 0.55 Ω·cm for high carbon ferromanganese;

– 0.25 ÷ 0.38 Ω·cm for ferrosilicon manganese.

Given that the relative sub-electrode gap for standard ferroalloy smelting typically ranges from 0.6 ÷ 0.9 electrode diameters, variations in bath resistance are significant and substantially affect furnace regulation.

By solving the system of equations derived from equation (1) (reflecting an increase in bath resistance) and equation (2) (indicating a decrease in the specific electrical resistance of the melting zone), the optimal sub-electrode gap was calculated. The results showed that the optimal sub-electrode gap for smelting is 3.33 electrode diameters. Under these conditions, the furnace parameters for ferrosilicon smelting achieved favorable values: power factor up to 0.939; electrical efficiency up to 0.921; thermal efficiency up to 0.364. Allowing for a ±5 % deviation from this optimal sub-electrode gap, ferroalloy smelting can be effectively performed within the range of 3.2 – 3.5 electrode diameters. However, operating with a larger sub-electrode gap would necessitate further increasing the bath depth.

Conclusions

The smelting of 45 % ferrosilicon by the carbon-thermal method, with an increased sub-electrode gap ranging from 0.6 ÷ 0.9 to 6.0 electrode diameters, leads to a 2.5-fold increase in bath resistance, voltage, and power. This increase is accompanied by a noticeable reduction in the specific electrical resistance of the furnace melting zone. The optimal sub-electrode gap was determined to be 3.33 electrode diameters. With an allowable deviation of ±5 %, ferroalloy smelting can be effectively carried out within the range of 3.2 – 3.5 electrode diameters.

References

1. Syvachenko V., Yemchytskyy V., Nezhuryn V. Direction of saving energy resources in the technology of electrothermical processes. In: Proceedings of the XIV Int. Ferroalloys Congress: INFACON XIV. Kiev, Ukraine. 31 May – 4 June 2015. Kiev; 2015:700–702.

2. Degel R., Lux T., Joubert H. Furnace integrity of ferroalloy furnaces – synbiosis of process, cooling, refractory lining and furnace design. In: Proceedings of the XV Int. Ferroalloys Congress: INFACON XV. Cape Town, South Africa. 25-28 February. Cape Town; 2018:269–282.

3. Grishchenko S.G., Kutsin V.S., Kravchenko P.A. Ferroalloy industry of Ukraine: Current status, development trends and future prospects. In: Proceedings of the XIV Int. Ferroalloys Congress: INFACON XIV. Kiev, Ukraine. 31 May – 4 June 2015. Kiev; 2015:1–5.

4. Degel R., Frіhling C., Koneke M. History and new milestones in submerged arc furnace technology for ferroalloy and silicon production. In: Proceedings of the XIV Int. Ferroalloys Congress: INFACON XIV. Kiev, Ukraine. 31 May – 4 June 2015. Kiev; 2015:7–16.

5. Gasik M. Handbook of Ferroalloys. Theory and Technology. Elsevier Ltd.; 2013:520. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2011-0-04204-7

6. Gasik M., Dashevskii V., Bizhanov A. Ferroalloys. Theory and Practice. Springer Nature Switzerland; 2020:328. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57502-1

7. Shkirmontov A.P. The role of sub-electrode gap in a ferroalloy furnace in improving the energy-technological parameters of smelting by carbon-thermal process. Elektrometallurgiya. 2017;(6):24–31. (In Russ.).

8. Shkirmontov A.P. Energy-Technological Parameters of Ferroalloy Smelting in Electric Furnaces. Moscow: NUST MISiS; 2018:216. (In Russ.).

9. Zhunusov A.K., Tolymbekov A.B. Metallurgical Processing of Manganese Ores from the TUR and Zapadny Kamys Deposits. Pavlodar: Keresku; 2016:209. (In Russ.).

10. Vorob’ev V.P. Electrothermy of Restorative Processes. Yekaterinburg: UB RAS; 2009:370. (In Russ.).

11. Bakirov A.G., Zhunusov A.K., Chekimbaev A.F. Shoshai Zh. Investigation of the electrical resistivity of charge mixtures for smelting ferrosilicoaluminium. Nauka i Tekhnika Kazakhstana. 2008;(2):14–19. (In Russ.).

12. Kozhevnikov G.N., Zaiko V.P. Electrothermy of Chromium Alloys. Moscow: Nauka; 1980:188. (In Russ.).

13. Nurmukhanbetov Zh.U., Kim V.A., Tolymbekov M.Zh. Electrical resistance of carbon reducing agents. Novosti nauki Kazakhstana. 2005;(2):35–40. (In Russ.).

14. Vorob’ev V.P. Carborundum-bearing carbon reducing agents in silicon and silicon-ferroalloy production. Steel in Translation. 2015;45(6):439–442. https://doi.org/10.3103/S0967091215060157

15. Ul’eva G.A. Investigation of the physico-chemical properties of special types of coke and its application for smelting high-silicon alloys: Extended Abstract of Cand. Sci. Diss. Yekaterinburg; 2013:23. (In Russ.).

16. Isin D.K., Baisanov S.O., Mekhtiev A.D., Baisanov A.S., Isin B.D. Technology for the production of crystalline silicon using non-traditional reducing agents. Metallurg. 2013;(11):88–93. (In Russ.).

17. Kim V.I. New types of carbon reducing agents for smelting of technical silicon. Stal’. 2017;(2):25–27. (In Russ.).

18. Shkirmontov A.P. Establishing the theoretical foundations and energy parameters for the production of ferroalloys with a larger-than-normal gap under the electrode. Metallurgist. 2009;53(5–6):300–308. https://doi.org/10.3103/s0967091222120117

19. Shkirmontov A.P. Change in active resistance of the bath and electrical resistivity of the reaction zone of ferrosilicon smelting with an increase in sub-electrode gap. In: Physico-Chemical Fundamentals of Metallurgical Processes: Int. Sci. Conf.: Proceedings. Moscow: IMET RAS; 2019:69. (In Russ.).

20. Strunskii B.M. Calculations of Ore-Thermal Furnaces. Moscow: Metallurgiya; 1982:192. (In Russ.).

21. Strunskii B.M. Ore-Thermal Melting Furnaces. Moscow: Metallurgiya; 1972:368. (In Russ.).

22. Sergeev P.V. Energy Patterns of Ore-Thermal Electric Furnaces, Electrolysis and Electric Arc. Alma-Ata: Izdatel’stvo AS Kazakh SSR; 1963:251. (In Russ.).

23.

About the Author

A. P. ShkirmontovRussian Federation

Aleksandr P. Shkirmontov, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Director of the Editorial Center of Scientific Journals

49/2 Leningradskii Ave., Moscow 125167, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Shkirmontov A.P. Sub-electrode gap and specific electrical resistance of a ferroalloy furnace bath. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2024;67(6):660-664. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-6-660-664