Scroll to:

Effect of annular seams on stress-strain state in cylindrical ceramic shell mold during solidification of a steel casting in it

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-613-620

Abstract

During the crystallization of liquid metal in a shell casting mold, significant normal stresses occur on its surfaces. On the inner – compressive, on the outer – tensile. They are especially pronounced at the initial moment of cooling time. This can lead to damage to the casting mold, and hence damage to the crystallizing metal casting. It is possible to reduce the level of stress-strain state in the surface layers by applying special annular (temperature) recesses (seams) to the outer and inner surfaces. In this paper, the problem of the influence of temperature seams in inner and outer layers of a shell mold (SM) on the level of its stress-strain state (SSS) during crystallization of a steel casting was formulated and solved. The normal stresses σ22 , σ33 , which occur both on the inner and outer surfaces of SM at the initial moment of metal casting and cooling of the steel casting, are accepted as a parameter of SM resistance to cracking. An axisymmetric problem for a cylindrical ceramic SM is considered. Based on the formulated objective function, the paper presents an algorithm for solving the problem using the equations of the linear theory of elasticity, the equation of thermal conductivity and the proven numerical method. As a result of solving the problem, the minimum number and locations of recesses on the inner and outer surfaces of SM, ensuring a decrease in normal stresses, were determined. The results of solving the problem are presented in the form of stress plots across the sections of the considered area. The authors analyzed the obtained results of SM resistance to cracking and gave recommendations on the use of the obtained results in various scientific and technical fields.

Keywords

For citations:

Evstigneev A.I., Odinokov V.I., Chernyshova D.V., Evstigneeva A.A., Dmitriev E.A. Effect of annular seams on stress-strain state in cylindrical ceramic shell mold during solidification of a steel casting in it. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):613-620. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-613-620

Introduction

Investment casting is widely used to produce geometrically complex castings while maintaining dimensional accuracy.

However, this process is characterized by a relatively high rejection rate of shell molds (SMs), primarily due to micro- and macrocracking as well as partial or complete mold failure during shape formation and, most critically, during key technological operations such as firing and metal pouring, especially at the early stage of cooling. These failures result from nonuniform heating across the thickness of the shell mold. Consequently, the limited durability of SMs is mainly associated with elevated stress–strain state (SSS) levels within the mold. To mitigate these effects, a range of technological solutions is applied in industrial practice.

The stress–strain state of multilayer shell casting molds has been extensively studied by both domestic and international researchers. In particular, studies [1; 2] examined the influence of shell mold shape and geometry; works [3; 4] focused on wall thickness; investigations [5; 6] addressed the properties of mold materials; and publications [7 – 9] analyzed the influence of casting geometry. Domestic studies dedicated to this problem are presented in [10 – 13]. Similar issues have also been investigated in relation to permanent mold casting [14; 15].

The present study continues the authors’ research on the crack resistance of ceramic SMs used in investment casting. In earlier work, the SSS of cylindrical SMs during pouring with liquid metal was investigated using mathematical modeling. The theoretical analysis identified optimal physical parameters of the SM material and its morphological structure as key factors governing crack resistance. These results formed the basis for the development of new SM designs and configurations, for which several Russian Federation patents for inventions have been granted (including Nos. 2743439 and 2763359).

The theoretical investigations are based on a numerical method [16] applied to the following problem: liquid metal is poured into a multilayer SM, where it solidifies to form a casting; during subsequent cooling, the temperature field and stress–strain state in the cross-sections of the SM are determined.

At the initial stage of the study, the analysis was performed for a casting in the form of a cylinder with a spherical rounding at the lower part, which simulates a riser-type casting model within a shell mold.

Further theoretical investigations of cylindrical SMs focused on quantifying how the force interaction with the supporting filler (SF) and the interlayer friction parameters within the shell mold affect its stress–strain state (SSS) [17; 18]. These results also led to the granting of Russian Federation patents (Nos. 2769192 and 2788296).

As shown by industrial monitoring of casting-mold durability, the most unpredictable casting geometry is spherical (ball-shaped). For spherical SMs, the optimal supporting-filler (SF) coverage angle and its effect on the stress–strain state (SSS) of the SM were determined in [19].

Foreign studies [20 – 22] present numerical-method-based mathematical modeling of these processes, whereas works [23; 24] address modeling of the SSS in a solidifying casting.

The search for technological solutions to reduce critical SSS levels in SMs led to a new ceramic SM design [25]. The proposed design builds on a well-known approach for reducing thermal stresses in castings by introducing so-called stiffening ribs [26].

It was shown that the durability of spherical SMs increases when annular (temperature) seams, or recesses, are introduced on the inner surface of the mold. A similar durability increase associated with such seams has also been reported for metal casting molds.

When steel is poured into a spherical shell mold, the internal normal stresses across the cross-section are fully compressive and reach relatively high values. Accordingly, the theoretical analysis focused on conditions that reduce the absolute magnitude of these stresses. The most effective solution was a shell mold design incorporating annular seams in the inner layer (lining) [25]. In contrast, for cylindrical shell molds, the greatest risk is associated with tensile normal stresses at the mold–SF contact surface.

In the present study, we consider a ceramic shell mold with a cylindrical section and theoretically analyze the effect of temperature seams not only in the outer layer of the shell mold but also on its inner surface. A “rigid” mold configuration is examined, namely a single-layer ceramic mold with a constant shear modulus.

Mathematical formulation of the problem

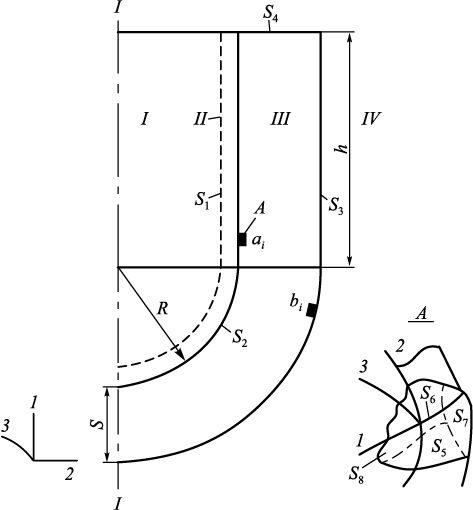

An axisymmetric body of revolution is considered (Fig. 1), comprising a liquid phase (metal) (I), a solidifying shell (II), a shell mold (III), a supporting filler (IV), circular recesses ai on the surface of the lining (surface S2 ), and circular recesses bi on the contact surface between the mold (III) and the supporting filler (IV) (surface S3 ).

Fig. 1. Calculation scheme of the system with indication of the surface |

Let A be a finite set of circular recesses ai on surface S2 ; A = {ai , i = 1, ..., n}; and let B be a finite set of circular recesses bi on surface S3 ; B = {bk , k = 1, ..., m}. Let C = A \( \cup \) B. As follows from the authors’ numerous studies, the critical stresses during steel pouring into a shell mold are σ22 and σ33 . Moreover, during steel cooling in a SM with cylindrical sections, the hazardous stresses are the tensile stresses σ22 on surface S3 , whereas during steel cooling in a shell mold of spherical configuration, the hazardous stresses are the compressive stresses σ33 on surface S2 .

Problem statement. Determine the minimum number and placement of recesses А on surface S2 of the shell mold and the number of recesses В on surface S3 , as well as their geometric arrangement, such that during metal cooling in the casting mold the maximum (absolute) stresses in the domain Q at τ = τ* remain within prescribed limits for the axisymmetric problem:

| \[\begin{array}{c}\left| {{\sigma _{33}}} \right| < 55{\rm{ MPa}};\\{\sigma _{22}} < 20{\rm{ MPa}},\end{array}\] | (1) |

here Q is the meridional cross-section domain; τ* is the maximum cooling time after which the temperature over the domain Q begins to equalize and the normal stresses σ22 and σ33 start to decrease in absolute value.

The value of τ* is determined from the function

| \[F = \max \left| {{\sigma _{33}}(\tau ,Q)} \right|,\] | (2) |

under the constraint τ ≤ 60 s.

To compute F, we write the governing equations in a Cartesian coordinate system for each subdomain (Fig. 1) using linear elasticity theory:

– domain I:

| \[\begin{array}{c}{\sigma _{11}} = {\sigma _{22}} = {\sigma _{33}} = \sigma = {P_1};\\{P_1} = - \gamma h;{\rm{ }}\dot \theta = {a_1}\Delta \theta ;\end{array}\] | (3) |

– domain II, III:

| \[\left\{ \begin{array}{l}{\sigma _{ij,j}} = 0,{\rm{ }}i,j = 1,{\rm{ }}2,{\rm{ }}3;\\{s_{ij}} - \sigma {\delta _{ij}} = 2{G_p}\varepsilon _{ij}^*;{\rm{ }}\varepsilon _{ij}^* = {\varepsilon _{ij}} - \frac{1}{3}\varepsilon {\delta _{ij}};{\rm{ }}\varepsilon = {\varepsilon _{ii}};\\{\varepsilon _{ii}} = 3{k_p}\sigma + 3{\alpha _p}\left( {\theta - \theta _p^*} \right);{\rm{ }}{\varepsilon _{ij}} = 0,5\left( {{U_{i,j}} + {U_{j,i}}} \right);\\{C_p}\gamma \frac{{\partial \theta }}{{\partial \tau }} = {\rm{div}}(\lambda {\rm{grad}}\theta ),\end{array} \right.\] | (4) |

where σij are the components of the stress tensor; σ is the hydrostatic stress; εij are the components of the elastic strain tensor; h is the height of the liquid metal column; \({k_p} = \frac{{1 - 2\mu }}{E}\) is the bulk compression coefficient; μ is Poisson’s ratio; E is Young’s modulus; Gp (θ) is the shear modulus in domain p (p = II, III); αp is the linear thermal expansion coefficient; a1 is the thermal diffusivity coefficient in domain (I); τ is time; θ is temperature; Cp is the specific heat capacity in domain (p); γ is the specific weight; \(\theta _p^*\) is the initial temperature in domain (p); λ = λ (θ) is the thermal conductivity coefficient; summation over repeated indices is implied.

During the cooling of liquid metal, under the condition that the metal temperature θm ≤ θc (where θc is the crystallization temperature), the thickness of the solidified layer Δi is determined from the solution of the phase-transition equation.

Initial conditions:

\({\left. \Delta \right|_{\tau = 0}} = 0\) – absence of solid phase;

\({\left. {\theta _I^*} \right|_{\tau = 0}} = \theta _{\rm{m}}^*\) – temperature of the poured liquid metal;

\({\left. {\theta _{III}^*} \right|_{\tau = 0}} = {\theta ^*}\) – initial mold temperature.

Boundary conditions of the problem in orthogonal coordinates (Fig. 1):

– for the axisymmetric problem

| \[\begin{array}{c}{U_3} = 0;{\rm{ }}{\sigma _{31}} = {\sigma _{32}} = 0;{\rm{ }}{\varepsilon _{13}} = {\varepsilon _{23}} = 0;\\\frac{{\partial {u_i}}}{{\partial {x_3}}} = 0;{\rm{ }}\frac{{\partial {\sigma _{3i}}}}{{\partial {x_3}}} = 0,{\rm{ }}i = 1,{\rm{ }}2,{\rm{ }}3;\end{array}\] | (5) |

– on the axis of symmetry

U2 = 0; σ21 = 0; qn = 0; θ = θm ;

– on surfaces S1 , S3 , S4

| \[\begin{array}{c}{\left. {{\sigma _{11}}} \right|_{{S_1}}} = - P;{\rm{ }}{\left. {{\sigma _{12}}} \right|_{{S_1}}} = 0;{\rm{ }}{\left. {{U_1}} \right|_{{{S'}_3}}} = 0;{\left. {{\rm{ }}{\sigma _{21}}} \right|_{{S_4}}} = 0;\\{\left. {{\sigma _{22}}} \right|_{{S_4}}} = 0;{\rm{ }}{\left. {{\sigma _{11}}} \right|_{{{S''}_3}}} = 0;{\rm{ }}\\{\left. {{\sigma _{12}}} \right|_{{{S'}_3}}} = - \psi \frac{{{U_{{\rm{sl}}}}}}{{{U^*}}}{\tau _s}\cos ({n_1}{x_1});{\rm{ }}\\{\left. \theta \right|_{{S_3}}} = {\theta ^*};{\rm{ }}{\left. \theta \right|_{{S_2}}} = {\theta _{\rm{m}}},\end{array}\] | (6) |

where Usl is the displacement of the mold material during sliding relative to the SF (sand), U* is the normalizing displacement; ψ is the friction coefficient between the mold and the supporting filler; τs is the conditional yield limit in shear; qn is the heat flux.

For the thermal analysis, we used Dirichlet (first-kind) boundary conditions. To determine θm (τ) and θ* (τ), the data from Ref. [27] were adopted:

| \[\begin{array}{c}{\theta _{\rm{м}}} = \theta _{\rm{m}}^* - \frac{\tau }{{{\tau _1}}}{\theta _1};\\0 < \tau < 60{\rm{ s}};\\{\theta ^*} = {\theta _0}\left( {1 + \sqrt {\frac{\tau }{{{\tau _2}}}} } \right),\end{array}\] | (7) |

here τ is the cooling time, s; \(\theta _{\rm{m}}^*\) = 1550 °С; θ1 = 100 °C; θ0 = 20 °С; θ* is the temperature on surface S3 ; τ1 = 60 s; τ1 = 1 s.

The time τ does not exceed 60 s, since for τ ≥ 60 s the stresses in the SM do not pose a risk of failure.

The shear modulus of the SM is taken as

| Gmold = 2960 kg/mm2. | (8) |

The algorithm for solving system (4) under boundary conditions (5) – (7) is described in detail in Ref. [27].

The calculation yielded the following results:

| F = –65.6 MPa; τx = 21.65 s. | (9) |

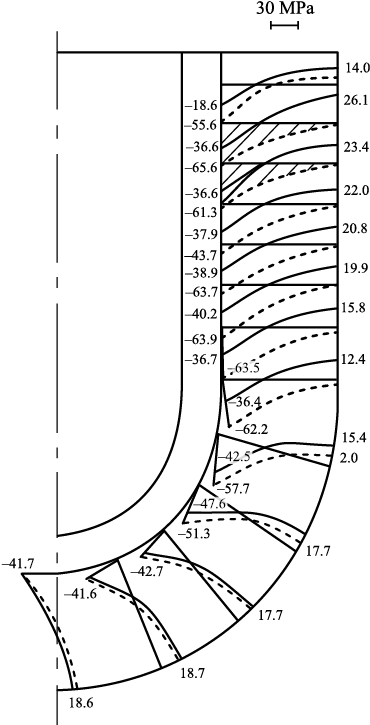

The solution results are presented in Fig. 2 in the form of stress plots along the cross-section of the shell under consideration. The stresses σ22 and σ33 are highly significant. In the lining, σ22 and σ33 are negative and reach large magnitudes in the cylindrical part of the SM, with |σ33| being approximately 1.5 times greater than |σ22|. In the spherical part, the difference between σ22 and σ33 is smaller; however, as the stresses approach the cylindrical region, the difference becomes pronounced. In the outer layer (at the contact with the supporting filler), the stresses σ22 are positive. In the spherical part, they are approximately equal in magnitude, whereas in the cylindrical part they increase toward the upper portion of the mold. The stresses σ33 on this surface (surface S3 ) are comparable to σ22 in the spherical region and are practically zero in the cylindrical region. Fig. 2 shows that the stresses σ33 and σ22 arising during steel pouring into the ceramic shell mold significantly exceed (in absolute value) the limits specified in (1).

Fig. 2. Stress plots σ22 ( |

Having determined the value of τ* from (9), we proceed to solving the formulated problem. The process of steel cooling in a ceramic SM with temperature seams (annular recesses) is considered. In contrast to the previous problem, the cross-section Q represents a multiply connected domain. The initial and boundary conditions largely coincide with those of the previous problem. Boundary conditions (6) are supplemented as shown in Fig. 1):

| \[{\left. {({\sigma _{22}} = {\sigma _{21}})} \right|_{{S_i}}} = 0,{\rm{ }}i = 5,{\rm{ }}6;{\left. {{\rm{ }}({\sigma _{11}} = {\sigma _{12}})} \right|_{{S_i}}} = 0,{\rm{ }}i = 7,{\rm{ }}8;\] | (10) |

Relationship (7) is also satisfied for the adopted value of the shear modulus given in (8).

Solution algorithm

1. The geometric dimensions of the domain, the final cooling time τ*, the geometric dimensions of the recesses, and their initial coordinates on surfaces S2 and S3 are specified: ai (0), bi (0). The cooling time τ* is divided into a finite number of time steps: \({\tau ^*} = \sum {\Delta {\tau _n}} \) (where n is the time-step index).

2. The investigated domain is divided into a finite number of elements by a system of orthogonal surfaces.

3. The arc lengths of the elements are calculated \(S_{ij}^k\) (i, k = 1, 2, 3; i ≠ k; j = 1, 2).

4. Initial and boundary conditions are specified for the elements forming the considered domain ((5), (6), (10)), as well as the constants of the physical and mechanical properties of the materials.

5. The temperature field at the time step Δτn is determined by a numerical solution of the heat conduction equation using an iterative scheme [27], taking into account the initial and boundary conditions at the given time step. The presence of recesses was not taken into account when solving the thermal problem.

6. If the condition \({\left. \theta \right|_{{S_2}}} \le {\theta _{\rm{c}}}\) for domain (I) at surface S2 , is satisfied, the thickness of the crystallized shell Δn is calculated.

7. System of equations (3) and (4) is solved taking in account boundary conditions (6) and (10), finite-difference analogs, and the developed methodology using the Odyssey software package1. The stress fields σij and displacement fields Ui (i, j = 1, 2) are determined.

8. On surface S3 , the mold–supporting contact is assessed for each element: if \({\left. {{\sigma _{11}}} \right|_{{S_3}}} > 0 \Rightarrow {\sigma _{11}} = 0,{\rm{ }}{\sigma _{12}} = 0\), the boundary conditions are reassigned and operation 7 is performed.

9. A time step is performed. According to relations (7) the boundary conditions for solving the thermal problem are refined. If \(\sum {\Delta {\tau _n}} < {\tau ^*}\), operation 5 is performed. If \(\sum {\Delta {\tau _n}} = {\tau ^*}\), operation 10 is performed.

10. Over the domain Q, the values of σ33 and σ22 are analyzed, and the maximum values (in absolute magnitude) exceeding the constraints (1) are selected. Corresponding matrices are formed \([{\bar \sigma _{22}}],{\rm{ }}[{\bar \sigma _{33}}]\). If constraints (1) are satisfied, operation 12 is performed.

11. From the matrices \([{\bar \sigma _{22}}],{\rm{ }}[{\bar \sigma _{33}}]\), the maximum values are selected, and recesses are introduced in the corresponding cross-sections. Operation 7 is then performed.

12. The calculation process is completed.

Results of the study

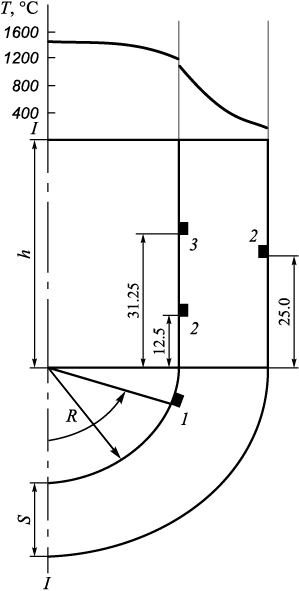

Geometric parameters: S = 5 mm; R = 20 mm; h = 50 mm.

Time intervals Δτn : 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 2, 5, 5, 5, 3, 3, 5, 5, 5, 5 s.

The following physical parameters of the poured steel at θ > 1000 °C (\(\theta _{\rm{m}}^*\) = 1550 °С) [27]:

G = 1000 kg/mm2; α = 12·10–6 deg–1;

λ = 0.0298 W/(mm·°C);

L = 270·103 J/kg (latent heat of fusion);

C = 444 J/(kg·°C); γ = 7.80·10–6 kg/mm3; θc = 1450 °C.

Physical properties of the ceramic shell mold:

G = 2960 kg/mm2; α = 0.51·10–6 deg–1;

λ = 0.000812 W/(mm·°C);

C = 840 J/(kg·°C); γ = 2.0·10–6 kg/mm3.

Recess dimensions: ai = 1×2 mm, bi = 1×3 mm.

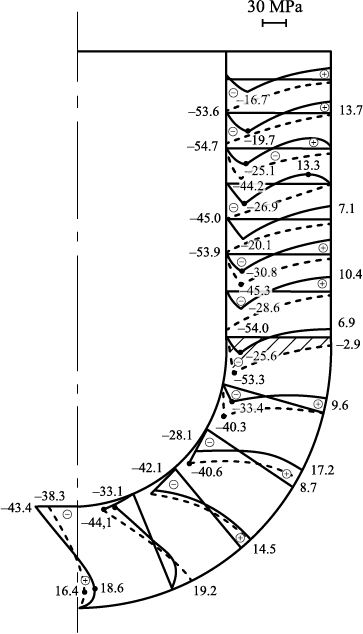

Calculations performed using the above algorithm yielded the following results: F = 5; ai = 2; bi = 3. The geometric locations of the recesses (ai , bi ) and the temperature distribution in the cross-section (x2 = 0) are shown in Fig. 3. The resulting stresses σ33 and σ22 are presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3. Calculation scheme of the system with a group

Fig. 4. Stress plots σ22 ( |

As shown in Fig. 4, all maximum values of the stresses σ33 (in absolute magnitude) and the tensile stresses σ22 satisfy the specified constraints (1), although in some cross-sections they are very close to the limiting values.

Conclusions

An axisymmetric problem was formulated and solved to optimize the cooling of a steel casting in a ceramic shell mold with cylindrical and spherical sections and annular temperature recesses.

The effectiveness of introducing annular recesses on the outer and inner mold surfaces in contact with the cooling metal was demonstrated.

The results can be used to analyze related processes, perform strength calculations, and support optimization studies.

References

1. Kanyo J.E., Schafföner S., Uwanyuze R.Sh., Leary K.S. An overview of ceramic molds for investment casting of nickel superalloys. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2020;40(15):4955–4973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.07.013

2. Rafique M.M.A., Iqbal J. Modeling and simulation of heat transfer phenomena during investment casting. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer. 2009;52(7-8):2132–2139. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2008.11.007

3. Singh R. Mathematical modeling for surface hardness in investment casting applications. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology. 2012;26:3625–3629. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12206-012-0854-0

4. Jafari H., Idris M.H., Ourdjini A. Effect of thickness and permeability of ceramic shell mould on in situ melted AZ91D investment casting. Applied Mechanics and Materials. 2014;465-466:1087–1092. http://dx.doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.465-466.1087

5. Bansode S.N., Phalle V.M., Mantha S. Taguchi approach for optimization of parameters that reduce dimensional variation in investment casting. Archives of Foundry Engineering. 2019;19(1):5–12. https://dx.doi.org/10.24425/afe.2018.125183

6. Pattnaik S., Karunakar D.B., Jha P.K. Developments in investment casting process ‒ A review. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2012;212(11):2332–2348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2012.06.003

7. Zhang J., Li K.W., Ye H.W., Zhang D.Q., Wu P.W. Numerical simulation of solidification process for impeller investment casting. Applied Mechanics and Materials. 2011; 80-81:961–964. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.80-81.961

8. Dong Y.W., Li X.L., Zhao Q., Yang J., Dao M. Modeling of shrinkage during investment casting of thin walled hollow turbine blades. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2017;244:190–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2017.01.005

9. Rakoczy Ł., Cygan R. Analysis of temperature distribution in shell mould during thin-wall superalloy casting and its effect on the resultant microstructure. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering. 2018;18(4):1441–1450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acme.2018.05.008

10. Golenkov Yu.V., Rybkin V.A., Yusipov R.F. Force interaction of support material with shell mold during investment casting. Liteinoe proizvodstvo. 1988;(2):14–15. (In Russ.).

11. Shpindler S.S., Neustruev A.A., Tserel’man N.M. Determination of thermal resistance of the casting-mold contact during investment casting. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 1986;29(9):97–100. (In Russ.).

12. Vasin Yu.P., Lonzinger V.A. Calculation of the heat resistance of shells during casting using moldable models. Liteinoe proizvodstvo. 1987;(2):19–21. (In Russ.).

13. Timofeev G.I., Ogorel’tsev V.P., Cherepnin A.Yu. Influence of temperature factor on stress-strain state of a shell mold. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 1990;33(8):69–71. (In Russ.).

14. Golofaev A.N. Calculation of stress-strain state of block molds by the finite element method. Liteinoe proizvodstvo. 1983;(5):16. (In Russ.).

15. Dembovskii V.V. Numerical modeling of castings forming in metal molds. Liteinoe proizvodstvo. 1992;(6):31–32. (In Russ.).

16. Odinokov V.I., Kaplunov B.G., Peskov A.V., Bakov A.V. Mathematical Modeling of Complex Technological Processes. Moscow: Nauka; 2008:178. (In Russ.).

17. Odinokov V.I., Evstigneev A.I., Dmitriev E.A., Chernyshova D.V., Evstigneeva A.A. Influence of support filler and structure of shell mold on its crack resistance. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2022;65(4):285–293. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2022-4-285-293

18. Odinokov V.I., Evstigneev A.I., Dmitriev E.A., Chernyshova D.V., Evstigneeva A.A. Morphological structure of shell mould in investment casting. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2022;65(10):740–747. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2022-10-740-747

19. Odinokov V.I., Dmitriev E.A., Evstigneev A.I., Namokonov A.N., Chernyshova D.V., Evstigneeva A.A. Modeling the stress-strain state and optimizing the angle of contact of a spherical shell mold by a support filler. Journal of Applied Mechanics and Technical Physics. 2025;66(1(389)):189–196. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.15372/PMTF202415455

20. Sabau A.S. Numerical simulation of the investment casting process. Transactions of American Foundry Society. 2005;113:407–417.

21. Zheng K., Lin Y., Chen W., Liu L. Numerical simulation and optimization of casting process of copper alloy water-meter shell. Advances in Mechanical Engineering. 2020;12(5): 1–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1687814020923450

22. Manzari M.T., Gethin D.T., Lewis R.W. Optimisation of heat transfer between casting and mould. International Journal of Cast Metals Research. 2000;13(4):199–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13640461.2000.11819402

23. Ogorodnikova O.M. Stress-strain state of metal in the effective range of crystallization. Liteinoe proizvodstvo. 2012;(9):21–24. (In Russ.).

24. Desnitskaya L.V., Desnitskii V.V., Matveev I.A. Consideration of the stress-strain state of solidifying steel castings in the process of their production. Liteinoe proizvodstvo. 2019;(4):6–8. (In Russ.).

25. Odinokov V.I., Evstigneev A.I., Dmitriev E.A., Evstigneeva A.A., Chernyshova D.V., Tkacheva Yu.I., Namokonov A.N. Casting multi-layer shell mold. Patent RF no. 2828801 C1, IPC B22C 9/04 (2006.01), B22C 9/08 (2006.01). Bulleten’ izobretenii. 2024. (In Russ.).

26. Foundry Production: Textbook for metallurgical specialties of universities: Mikhailov A.M. ed. Moscow: Mashinostroenie; 1987:256. (In Russ.).

27. Odinokov V.I., Dmitriev E.A., Evstigneev A.I., Sviridov V.I. Mathematical Modeling of the Processes of Obtaining Castings in Ceramic Shell Molds. Moscow: Innovatsionnoe mashinostroenie; 2020:256. (In Russ.).

About the Authors

A. I. EvstigneevRussian Federation

Aleksei I. Evstigneev, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Prof., Chief Researcher of the Department of Research Activities

27 Lenina Ave., Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk Territory 681013, Russian Federation

V. I. Odinokov

Russian Federation

Valerii I. Odinokov, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Prof., Chief Researcher of the Department of Research Activities

27 Lenina Ave., Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk Territory 681013, Russian Federation

D. V. Chernyshova

Russian Federation

Dar’ya V. Chernyshova, Postgraduate of the Chair of Aircraft Engineering

27 Lenina Ave., Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk Territory 681013, Russian Federation

A. A. Evstigneeva

Russian Federation

Anna A. Evstigneeva, Student

27 Lenina Ave., Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk Territory 681013, Russian Federation

E. A. Dmitriev

Russian Federation

Eduard A. Dmitriev, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Prof., Assist. Prof., Rector

27 Lenina Ave., Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk Territory 681013, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Evstigneev A.I., Odinokov V.I., Chernyshova D.V., Evstigneeva A.A., Dmitriev E.A. Effect of annular seams on stress-strain state in cylindrical ceramic shell mold during solidification of a steel casting in it. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):613-620. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-613-620