Scroll to:

Contact characteristics of C235 steel in dry sliding against C45 steel under high-density alternating current at different transformation coefficients of supply transformer

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-587-593

Abstract

The authors studied the tribotechnical behavior of C235 steel under conditions of dry sliding electrical contact with a current density of more than 100 A/cm2 at different transformation coefficients of the supply transformer. A decrease in the transformation coefficient leads to a decrease in the wear resistance and electrical conductivity of the contact. Metallographic methods revealed the formation of transfer layers on the contact surfaces. Thickness of the transfer layers does not exceed 20 μm. Morphological patterns of worn contact surfaces on the scale of the nominal (geometric) contact area consist of two sectors, where one sector has signs of melting. X-ray phase analysis has shown that the transfer layers contain more than 70 vol. % FeO. That is why the transfer layers could be represented as a quasi-dielectric medium, where FeO acts as a dielectric. The authors assume that strong self-induction pulses occur in the contact zone, which cause high-density displacement currents. These currents act directly on FeO ions and convert them into a melt. These concepts allow us to assert that the melt consists of atoms or ions of iron and oxygen. A decrease in the transformation coefficient (that is, an increase in the inductance of the secondary winding of the supply transformer) causes an increase in self-induction pulses and displacement currents, which leads to an increase in the amount of FeO melt, its easy removal from the contact area, and a corresponding decrease in the wear resistance and electrical conductivity of the contact. The data obtained can serve as guidelines when choosing wear-resistant materials for high-current sliding contact and, in particular, when defining its design.

Keywords

For citations:

Aleutdinova M.I., Fadin V.V. Contact characteristics of C235 steel in dry sliding against C45 steel under high-density alternating current at different transformation coefficients of supply transformer. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):587-593. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-587-593

Introduction

One of the primary objectives of tribology is to ensure satisfactory wear resistance of friction pairs under severe operating conditions. This can be achieved through the appropriate design of the friction unit, the desired environmental conditions, or the selection of appropriate friction pair materials. Dry sliding under high-density electric current is one of the extreme types of external influences on contact zone materials. Known current collector materials are typically operated under current densities of 15 – 40 A/cm2 during dry sliding against a copper counterbody. Generally, known current collector materials are not used for dry sliding at current densities exceeding 60 A/cm2 [1], as such sliding leads to rapid deterioration of the friction pair contact layers.

Material sliding under high-density currents (higher than 100 A/cm2) is of scientific and practical interest. A tribosystem with current collection must have contact layers whose condition ensures high wear resistance and high electrical conductivity of the contact. It is known [2] that high electrical conductivity of a metal/steel sliding contact typically corresponds to high wear resistance under high current density. Therefore, increasing the electrical conductivity of a sliding electrical contact can simultaneously increase its wear resistance. Changing the design parameters of the current collector unit can lead to improved contact characteristics.

A sliding electrical contact can be implemented by incorporating a friction unit into the secondary power winding circuit of a transformer. One of the fundamental equations of an ideal transformer can be written as

i1 – хх n1 = i1n1 + i2 n2

or

\[{i_2} = \frac{{({i_{1 - xx}} - {i_1}){n_1}}}{{{n_2}}} = ({i_{1 - xx}} - {i_1})k,\]

where n1 and n2 are the number of turns in the primary and secondary windings, respectively; i1 – хх is the current in the primary winding when the transformer is no-load (i2 = 0); i1 and i2 are the currents in the primary and secondary coils when the secondary winding is loaded (i2 > 0); k = n1/n2 is the turn ratio.

It is clear from this that the value of i2 = (i1 – хх – i1)k can formally be increased by increasing k under certain conditions. The current i2 is the contact current (i2 = iс ) and its increase at a low contact voltage drop will correspond to an increase in the contact conductivity. Therefore, the assumption that the contact current i2 = iс increases with increasing k = n1/n2 should be verified experimentally. Some metals (tungsten, molybdenum, etc.) are not capable of sliding against steel with high contact conductivity, so they cannot serve as model materials for these experiments. C235 steel is the most convenient model material.

The aim of this study is to determine the regularities of change in the electrical conductivity of a dry sliding steel/steel electrical contact and its wear resistance at different turn ratios of the power transformer.

Experimental materials and methods

Low-carbon steel C235 (0.2 % C) served as the material for the cold-worked samples with a diameter of 3.5 mm and a height of 8 mm. The sliding surfaces were examined using an optical microscope (OM, Axiovert 200 M). The hardness of the samples (Нμ = 2.1 GPa) was determined using a Micro-Vickers TVM-5215-A micro-hardness tester under a load of 1 N. X-ray phase analysis of the sample contact layers was performed using a DRON-7 diffractometer in CoKα radiation. The volume content of phases in the contact layer was determined according to a known method [3; 4], where the intensity of the X-ray wave IHKL – j , scattered from the reflecting plane (HKL) of a certain crystalline j-th phase, was written as

| IHKL – j = I0 k0 KHKL – j cv – j , | (1) |

where I0 is the intensity of the X-ray wave incident on the multiphase surface; k0 is a coefficient that takes into account the geometric parameters of the X-ray apparatus; KHKL – j is a complex proportionality coefficient for the j-th phase; cv – j is the volume concentration of the given j-th phase in the multiphase medium.

The qualitative phase composition and the integrated intensities of the KHKL – j peaks should be found from the X-ray diffraction patterns (Fig. 1, b), the necessary reference data can be found in [4]. Taking into account that Σcv – j = 1, the volume concentrations of the phases can be found.

Fig. 1. Scheme of sliding electrical contact of pin-on-ring configuration (a) |

The materials were loaded by dry friction under alternating current (50 Hz) at a contact pressure of р = 0.13 MPa and a sliding velocity of v = 5 m/s using the well known pin-on-ring configuration (Fig. 1, a). Chromel-Copel thermocouples T1 , T2 , T3 were fixed to the sample holder with screws. The linear wear intensity was defined as Ih = h/D (where h is the change in sample height per a sliding distance D). The contact current density was defined as j = i2 /Aa (where i2 is the contact current; Aa is the nominal contact area). The specific surface electrical conductivity of the contact was defined as σA = j/U (where U is the contact voltage drop). The friction coefficient was determined using a ZET7111 strain gauge. Before testing, the samples were lapped against a counterbody (C45 steel (Нμ = 5.8 GPa)). Each test was performed three times.

Results

It is evident that the initial structure of the surface layers of C235 steel specimens before friction contains the α-Fe phase predominantly. Peak α-Fe, high-intensity FeO peaks, and low-intensity γ-Fe peaks are observed in the X-ray diffraction patterns of the contact layers of the steel specimens after friction (Fig. 1, b). The FeO and γ-Fe phases appeared on the surface of the specimens under the influence of friction and current. The intensities of the strongest peaks I200 (FeO), I111 (γ-Fe), and I110 (α-Fe) were inserted into equation (1) and the volume concentrations cv – j of these phases in the contact layers of the specimens after friction were calculated for any k value (see Table). It is evident that FeO is the main phase in the contact layers. The γ-Fe concentration is low for any k value and is not of interest for discussion. The lattice parameters of the α-Fe, γ-Fe and FeO phases are generally close to the lattice parameters of the same phases from the ASTM database.

Volumetric concentrations of phases in the contact layer of C235 steel

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

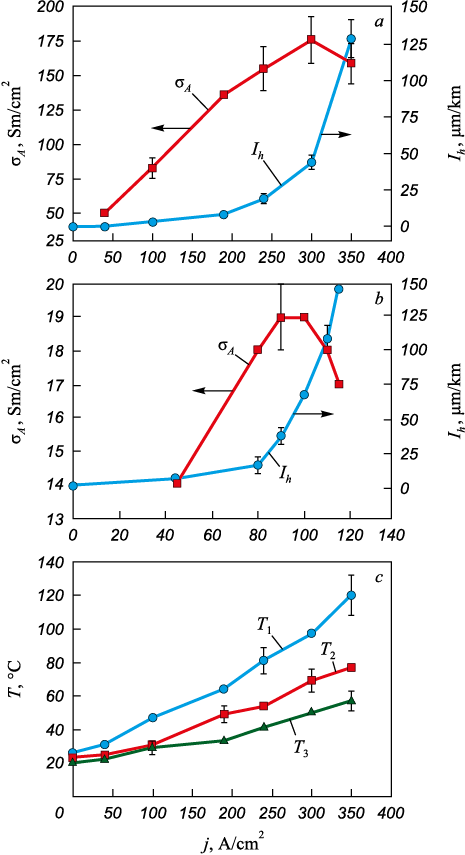

It is obvious that FeO and γ-Fe phases appeared under the influence of current, temperature and plastic deformation of the contact layers of the samples. Deformation and deterioration of the contact layers occur under frictional fatigue conditions. Current density is the main factor determining fatigue deterioration (wear) of the electrical contact zone. An increase in current density j in the contact causes an increase in the wear intensity Ih for any value of k (Fig. 2, a, b). The current dependence of the electrical conductivity σA of the contact has positive slope in the range of j < 300 A/cm2 at k = 67 and in the range j < 100 A/cm2 at k = 18. At j > 100 A/cm2 and j > 300 A/cm2 (Fig. 2, a, b), a sharp increase in Ih occurs, which indicates the onset of catastrophic wear. At the same time, the slopes of the σA (j) curves become negative. It is also evident that σA (j) for the contact at k = 67 is significantly higher than for k = 18. But Ih is significantly lower for the contact at k = 67 than that for k = 18.

Fig. 2. Токовые зависимости интенсивности изнашивания (Ih ) |

The friction coefficient depends weakly on k; during sliding without current f ≈ 0.7 and decreases to f ≈ 0.4 with increasing j. The temperatures (Т1 , Т2 , Т3 ) of the side surface of the specimen holder are indicators of the thermal state of the specimen and the specimen holder. The T(j) dependences are nonlinear (e.g., Fig. 2, c). Changing of k does not significantly affect the nature of the T(j) curves or the numerical values of the temperatures, which can exceed 100 °C. This may indicate the similarity of the thermal states of the specimen contact layers during sliding at different k in the normal wear regime, that is, before the catastrophic wear onset.

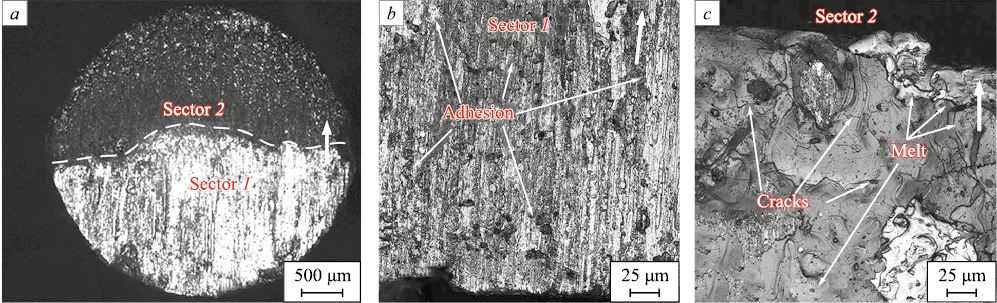

The worn surfaces of the specimens have approximately the same images at any k value; namely, the contact surface is divided into two sectors with different morphological details (Fig. 3, a). Sector 1 (light area in Fig. 3, a) is formed on the frontal part of the nominal contact area of the samples, i.e. sector 1 faces the oncoming sliding surface of the counterbody (Fig. 1, a). Plastic deformation and wear in sector 1 occur due to adhesion and plowing by the counterbody asperities (Fig. 3, b), which is described for normal friction without current, for example, in [5; 6]. The contact layers in sector 2 are deformed mainly by the viscous fluid mechanism, which is shown in detail in Fig. 3, c. This should facilitate a sufficiently rapid stress relaxation. There is a certain transition zone between these sectors, more than 10 μm long (for these friction pairs), where both deformation mechanisms considered are realized simultaneously. It should be noted that the appearance of a melt in the contact zone is not accompanied by its glow. This means that the temperature of the contact zone is lower than 600 °C and the nature of the melt must be established.

Fig. 3. Nominal contact area (a) and morphological images of worn surfaces of C235 steel samples |

Discussion

It was noted above that the morphological features of the worn surfaces are identical, and the failure mechanisms of the contact surfaces do not differ significantly. The phase compositions of the contact layers are also approximately the same (see Table). The values of the thermal power (fpv + jU) of the external impact, corresponding to the catastrophic wear onset, are approximately the same, which can be calculated from Fig. 2, a, b. Obviously, the slight difference in these output parameters of a tribosystem with current collection cannot serve as a satisfactory basis for understanding the difference in the rate of contact layer failure at different values of the turn ratio k. It should be noted that sliding without current in the presence of oxides (e.g., [7 – 10]) and in the absence of oxides (e.g., [11 – 13]) in the contact zone does not lead to the formation of melt on the contact surfaces. The formation of melt was also not observed during sliding under low-density current [14 – 16] or under high-density current [17]. The steel/steel contact surfaces in the present study showed no signs of melting at j > 700 A/cm2 in stationary contact (v = 0 m/s). These data and the presented observations (Fig. 2 and Table) suggest that melting occurs at a certain sliding velocity (v > 0 m/s), at a certain current density (j > 0 A/cm2), and at a certain FeO concentration (сFeO > 0).

In general, the total current density j0 (in any conducting circuit) and, in particular, the total current density in the contact can be written as j0 = jf + jD (where jf is the current density of free charges; jD is the bias current density (i.e., the current density of bound charges)). The transfer layers contain a dielectric (FeO) with ionic polarization; here, the bound charges are ions in FeO crystals. Obviously, an increase in jD should cause an increase in the energies of oxygen and iron ions in FeO crystals. It should be taken into account that adhesion and roughness in any dry contact always determine the intermittent nature of sliding in the stick-slip mode. This leads to current oscillations in the contact and to corresponding self-induction pulses. Usually, the self-induction EMF (electric moving force) is written as ĕ = –Ldi/dt (where L is the inductance of the conducting circuit; i is the current in the conducting circuit). The design of the friction unit (Fig. 1, a) contains an inductance L in the secondary winding of the transformer supplying power to the sliding contact (where L ~ n2; n is the number of turns in the winding). The appearance of an EMF pulse (ĕ) in the contact sets the electric field strength E in the contact, so we can approximately write ĕ = –Ldi/dt ≈ |E|h0 (where h0 is a parameter that can characterize the interval of gradient of the electric field in the contact, m). Now, knowledge of the parameter h0 is not important, since it is necessary to show an increase in E with an increase in L. An increase in self-induction pulses with an increase in L should cause an increase in Е, ∂Е/∂t and, accordingly, jD . It should be noted that the turn ratio of the power transformer decreases with an increase in L. In addition, the voltage in the contact during self-induction pulses can significantly exceed the average voltage between the contact surfaces. These pulsed voltages determine high values of Е, ∂Е/∂t and corresponding jD , capable of deteriorating the FeO crystal lattice and transferring FeO ions into the melt (Fig. 3). The highest values of jD should be in the vicinity of the contact spots; therefore, melt should appear only at the contact spots and their vicinity, and only during the existence of the self-induction pulse. Obviously, an increase in jD by increasing E (in particular, by increasing L) will lead to an increase in the energy of the self-induction pulse, to higher loads at the contact spots, and to more intense deterioration of the transfer layer. It is possible that relatively strong self-induction pulses, corresponding to a high inductance L, cause the formation of relatively large volumes of melt with low viscosity. The last two factors (large melt volume and its low viscosity) contribute to the acceleration of the deterioration of the transfer layer. For this reason, the melt should not be considered as a good lubricant. This means that an increase in L (i.e., a decrease in k) leads to a higher Ih (Fig. 2, a, b).

It is to be expected that the melt layer thickness is smaller than the transfer layer thickness. The presence of melt predominantly in sector 2 suggests that the FeO concentration is higher in this sector than in sector 1. This indicates a general unevenness of FeO distribution in the transfer layer. The steel/steel contact parameters presented here correspond to a circular nominal contact area. The values of these parameters are close to the values corresponding to rectangular nominal contact areas [18]. It should be noted that melt can appear at a low oxide concentration in a contact layer having two sectors (e.g. W/Mo or W/steel contacts [19], as well as steel/steel, where there is only melt [20]). Quite similar morphological types and phase compositions of transfer layers containing more than 70 vol. % FeO allow us to expect the manifestation of these features in many metal/steel contacts during sliding under current.

Conclusions

Dry sliding of C235 steel against hardened grade C45 steel was performed under alternating electric current with a density higher than 100 A/cm2 while varying the turn ratio of the power transformer in this study. The turn ratio was reduced by increasing the inductance of the transformer’s secondary supply winding.

A decrease in the turn ratio resulted in a decrease in contact conductivity, an increase in wear intensity and a decrease in current density, corresponding to the catastrophic wear onset.

In the sliding contact zone under current, transfer layers are formed, which have two morphologically different sectors on the worn surfaces at different turn ratios: one sector shows signs of deformation due to adhesion, while the other sector is deformed with melt formation.

It was found that the transfer layers contain more than 70 vol. % FeO.

An explanation for melt formation has been proposed: high bias currents arise from strong self-induction pulses in the contact, which remove Fe2+ and O2– ions from the FeO crystal lattice nodes and cause melting of the contact layer.

A decrease in the turn ratio causes high self-induction pulses and correspondingly high bias current densities. This results in a relatively strong energy impact on the contact layer and its high wear.

References

1. Braunovich M., Myshkin N.K., Konchits V.V. Electrical Contacts. Fundamentals, Applications and Technology. CRC Press; 2007:672.

2. Aleutdinova M.I., Fadin V.V. Variations in the contact layer structure of low-carbon steel in sliding against a steel counterbody with different nominal contact areas under a high-density electric current. Russian Physics Journal. 2023;66(6):605–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11182-023-02982-5

3. Waseda Y., Matsubara E., Shinoda K. X-Ray Diffraction Crystallography. Introduction, Examples and Solved Problems. Springer; 2011:322.

4. Mirkin L.I., Otte H.M. Handbook to X-Ray Analysis of Polycrystalline Materials. Springer; 1964:732.

5. Kragelsky I.V., Dobychin M.N., Kombalov V.S. Friction and Wear Calculation Methods. Pergamon Press; 1982:464.

6. Bowden F.P., Tabor D. Friction: An Introduction to Tribology. R.E. Krieger Publishing Company; 1982:178.

7. Wang S.Q., Wang L., Zhao Y.T., Sun Y., Yang Z.R. Mild-to-severe wear transition and transition region of oxidative wear in steels. Wear. 2013;306(1-2):311–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2012.08.017

8. Kumar N., Gautam G., Gautam R.K., Mohan A., Mohan S. Wear, friction and profilometer studies of insitu AA5052/ZrB2 composites. Tribology International. 2016;97:313–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2016.01.036

9. Straffelini G., Trabucco D., Molinari A. Oxidative wear of heat-treated steels. Wear. 2001;250(1-12):485–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1648(01)00661-5

10. Fadin V.V., Kolubaev A.V., Aleutdinova M.I. Оn wear resistance of steel-containing composites under extreme friction conditions. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2019;62(8): 621–626. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2019-8-621-626

11. Kato H., Todaka Y., Umemoto M., Haga M., Sentoku E. Sliding wear behavior of sub-microcrystalline pure iron produced by high-pressure torsion straining. Wear. 2015; 336-337:58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2015.04.014

12. Deng S.Q., Godfrey A., Liu W., Zhang C.L. Microstructural evolution of pure copper subjected to friction sliding deformation at room temperature. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2015;639:448–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2015.05.017

13. Bansal D.G., Eryilmaz O.L., Blau P.J. Surface engineering to improve the durability and lubricity of Ti–6Al–4V alloy. Wear. 2011;271(9-10):2006–2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2010.11.021

14. Zhaо H., Feng Yi., Zhou Z., Qian G., Zhang J., Huang X., Zhang X. Effect of electrical current density, apparent contact pressure, and sliding velocity on the electrical sliding wear behavior of Cu–Ti3AlC2 composites. Wear. 2020;444-445: 203156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2019.203156

15. Kubota Y., Nagasaka S., Miyauchi T., Yamashita C., Kakishima H. Sliding wear behavior of copper alloy impregnated C/C composites under an electrical current. Wear. 2013;302(1-2):1492–1498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2012.11.029

16. Dong L., Chen G.X., Zhu M.H., Zhou Z.R. Wear mechanism of aluminum–stainless steel composite conductor rail sliding against collector shoe with electric current. Wear. 2007;263(1-6):598–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2007.01.130

17. Argibay N., Bares J.A., Keith J.H., Bourne G.R., Sawyer W.G. Copper–beryllium metal fiber brushes in high current density sliding electrical contacts. Wear. 2010;268(11-12): 1230–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2010.01.014

18. Aleutdinova M.I., Fadin V.V. Wear behavior of metals in dry sliding against molybdenum with current collection. Inorganic Materials: Applied Research. 2020;11(6):1378–1382. https://doi.org/10.1134/S2075113320060027

19. Aleutdinova M.I., Pochivalov Yu.I., Fadin V.V. Viscous plastic flow in contact layers as a method of stress relaxation in dry sliding of steel against steel under electric current. Materials Letters. 2022;328:133050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2022.133050

20. Behtash Amir M.K., Alpas A.T. Effect of electrical current on sliding friction and wear mechanisms in a-C and ta-C amorphous Carbon coatings. Wear. 2025;560-561:205608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2024.205608

About the Authors

M. I. AleutdinovaRussian Federation

Marina I. Aleutdinova, Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Research Associate of the Laboratory of Physics of Surface Hardening

2/4 Akademicheskii Ave., Tomsk 634055, Russian Federation

V. V. Fadin

Russian Federation

Viktor V. Fadin, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Assist. Prof, Senior Researcher of the Laboratory of Physics of Surface Hardening

2/4 Akademicheskii Ave., Tomsk 634055, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Aleutdinova M.I., Fadin V.V. Contact characteristics of C235 steel in dry sliding against C45 steel under high-density alternating current at different transformation coefficients of supply transformer. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(6):587-593. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-6-587-593