Scroll to:

Peculiarities of the phase composition formation of steelmaking slags and evaluation of the possibility of obtaining mineral binders with low CO2 generation on their basis

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-2-179-187

Abstract

The article presents the results of analysis of steelmaking slags formation. It is shown that currently two methods of steel refining are used in the steelmaking industry – oxidative and reducing. The method of oxidative refining is implemented in electric arc furnaces (EAF), and is primarily aimed at extracting phosphorus from the steel being smelted. Reducing refining is implemented in the ladle-furnace unit (LF) and is aimed at removing sulfur from steel. The features of these processes affect the formation of the phase composition of steelmaking slags. Under conditions of oxidative refining, wustite FeO, magnetite Fe3O4 , larnite β-2CaO·SiO2 and merwinite 3CaO·MgO·2SiO2 are formed in EAF slags, and under conditions of reducing refining in LF slags, mayenite 12CaO·7Al2O3 , periclase MgO, low–temperature modification of dicalcium silicate – γ-2CaO·SiO2 , CaS and FeO. Of the minerals in the composition of EAF slags and LF slags, mayenite 12CaO·7Al2O3 and larnite β-2CaO·SiO2 have hydraulic activity. Based on the theoretical analysis of the formation of sulfated hydraulically active phases, the possibility of imparting properties of mineral binders to steelmaking slags by grinding without their additional thermal preparation is shown.

Keywords

For citations:

Sheshukov О.Yu., Mikheenkov M.A., Egiazar’yan D.К., Mikheenkov А.M., Kleonovskii M.V., Matyukhin O.V. Peculiarities of the phase composition formation of steelmaking slags and evaluation of the possibility of obtaining mineral binders with low CO2 generation on their basis. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(2):179-187. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-2-179-187

Introduction

At the turn of the 21st century, the steelmaking industry underwent radical changes. Due to increasing quality requirements for steel products combined with the declining quality of raw materials, high-intensity steel melting in ultra-high-power electric arc furnaces and methods of secondary steel treatment have become widespread. This led to changes in the structure and quality characteristics of steelmaking slags. In the previous century, the most common methods of steel production were the converter and open-hearth processes. The slags formed under such conditions had a stable crystalline structure, and their storage and processing did not pose significant challenges. The processing of these slags into commercial products was mainly carried out using the simplest methods – magnetic separation, crushing, and particle size classification – to meet the requirements of GOST 3344–83 “Slag crushed stone and sand for road construction. Technical specifications” [1].

The conditions for the formation of the phase and chemical composition of slags in the steelmaking industry have changed significantly in recent years. The open-hearth method has become obsolete and is no longer used. Under modern conditions, two methods of steel refining are used in the steelmaking industry – oxidative and reducing. Oxidative refining is implemented in converter units and electric arc furnaces (EAF) and is primarily aimed at extracting phosphorus from the steel being smelted, while reducing refining is implemented in the ladle-furnace unit (LF) and is aimed at removing sulfur from steel. The specific features of these processes influence the formation of the phase composition of steelmaking slags.

The aim of this study is to analyze the specific features of steelmaking slag formation under current steel production conditions and to develop an optimal method for obtaining mineral binders based on these slag.

Peculiarities of steelmaking slag formation

The processes of oxidative refining, carried out in converter and electric arc furnaces, differ only slightly, and the slags formed in these units are similar in terms of their phase and chemical composition. To ensure effective oxidative refining, a significant amount of burnt lime (CaO) is added to the furnace at the beginning of the melt. As a result of the interaction between CaO and the mill scale on the scrap metal, as well as with iron oxides formed during the oxygen blowing of molten steel, lime is assimilated and low-basic (CaO·Fe2O3 ) and high-basic (2CaO·Fe2O3 ) forms of calcium ferrite are formed in the slag. Simultaneously, during the oxygen blowing of molten steel, phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5 ) enters the slag. SiO2 , an acidic oxide that enters the furnace along with contaminated scrap, displaces the amphoteric iron (III) oxide (Fe2O3 ) from calcium ferrite, forming two silicate phases in the slag – dicalcium silicate (β-2CaO·SiO2 ) and merwinite (3CaO·MgO·2SiO2 ). At the same time, iron oxides enter the slag as independent phases. The dicalcium silicate formed in the slag exhibits a high-temperature polymorphic β-modification, known as larnite [2]. The formation of larnite in the slag is accompanied by partial isomorphic substitution of silicon-oxygen tetrahedra in the dicalcium silicate molecule by phosphorus pentoxide, which enters the slag during oxygen blowing. Due to the substitution of ions \({\rm{SiO}}_4^{4 - }\) in the dicalcium silicate molecule by ions \({\rm{PO}}_4^{3 - }\), its ionic stabilization occurs, preventing the disintegration of dicalcium silicate during cooling. The other silicate phase, merwinite, is a magnesium-substituted analogue of dicalcium silicate. Magnesium oxide (MgO) forms due to the partial erosion of the periclase-based furnace lining by slag. As a result of all these processes, the final phase composition of the oxidative refining slag is formed [3], and consists of wustite (FeO) – 20.4 %, magnetite (Fe3O4 ) – 24.1 %, larnite (β-2CaO·SiO2 ) – 38.15 %, merwinite (3CaO·MgO·2SiO2 ) – 15.9 %, and impurities – 1.45 %.

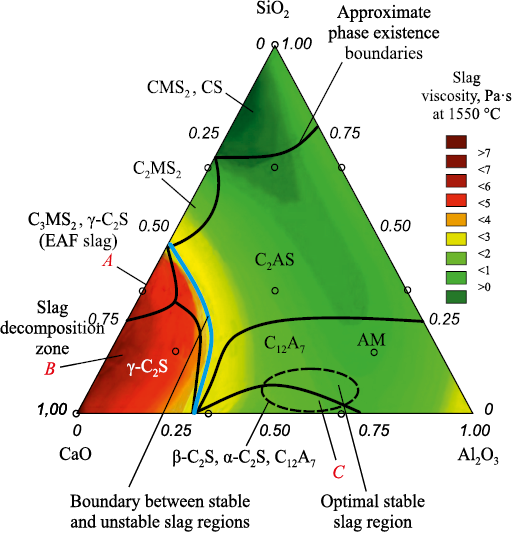

Steel from EAFs and converters is transferred to ladle units, where reducing refining is carried out in the ladle-furnace (LF) unit. When metal is tapped from the EAF or converter into the ladle, an effort is made to remove as much slag as possible. Nevertheless, a portion of the oxidative slag inevitably enters the ladle, forming the initial slag during the early stage of reducing refining. The phase composition of LF slag, as plotted on the CaO – SiO2 – Al2O3 phase diagram and determined by the authors in studies on slag stabilization methods [2], is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Phase composition of LF slag [2] |

Many of the identified phases contain magnesium oxide, since pure CaO was not used in phase formation; instead, a model slag with a chemical composition corresponding to typical LF slag containing approximately 10 % MgO was employed. Area A in Fig. 1 corresponds to the phase composition of EAF slag that entered the LF unit from the ladle iron, and only two phases remain in area A – dicalcium silicate (β-2CaO·SiO2 ) and merwinite (3CaO·MgO·2SiO2 ). To enable desulfurization, burnt lime (CaO) is added to the LF unit, which reacts with merwinite and causes its decomposition according to the reaction

| 3СаO·MgO·2SiO2 + СаO = 2(2СaO·SiО2) + MgO. | (1) |

This phase composition corresponds to area B in Fig. 1. The interaction of free lime with sulfur in the metal leads to the following reaction

| [FeS] + (СаО) = (CaS) + (FeO). | (2) |

In area B, the slag viscosity is elevated, which hinders the desulfurization process. To reduce the viscosity, an alumina-based flux is added to the slag, and in area C (Fig. 1), the final phase composition of LF slag is formed [2], consisting of mayenite (12CaO·7Al2O3 ) – 37.2 %, periclase (MgO) – 12.5 %, dicalcium silicate (α-2CaO·SiO2 ) – 41.4 %, approximately 1 % CaS, and the remainder FeO. During the cooling of LF slag, polymorphic transformations occur in the dicalcium silicate phase [2]. Five polymorphic modifications of dicalcium silicate are known, three of which are high-temperature forms (α, \({\alpha '_{\rm{s}}}\) and \({\alpha '_L}\), and their successive transformations during cooling do not cause critical changes in LF slag. Since reducing conditions are maintained in the LF, iron oxides from the EAF slag are rapidly reduced to metallic a critical transformation is the polymorphic transition of larnite to shennonite1. Larnite (β-2СaO·SiО2 ) is a metastable modification of dicalcium silicate that, upon cooling below 525 °C, slowly transforms into shennonite (γ-2CaO·SiO2 ). Since the true density of larnite (β-2CaO·SiO2 ) is 3.28 g/cm3 and that of shennonite (γ-2CaO·SiO2 ) is 2.97 g/cm3, this polymorphic transformation leads to a 12 % volume increase, causing the slag to disintegrate into a powder-like fraction. As a result of these processes, larnite (β-2CaO·SiO2 ) is absent in cooled LF slag, and shennonite (γ-2CaO·SiO2 ) is present instead.

Literature review

The changed conditions of slag formation in the steelmaking industry and the resulting phase composition require a more advanced approach to slag processing, taking into account current knowledge and developments in the formation of mineral binding agents based on such slags.

Due to stricter CO2 emission regulations and environmental challenges associated with the storage and recycling of steelmaking slags, global efforts are being made to partially or completely replace components in general construction concrete – such as ordinary Portland cement, coarse aggregates (crushed stone, gravel), and fine aggregates (quartz sand). In [4], the use of converter slag with particle sizes of 5 – 20 mm as a substitute for coarse aggregates, and 0 – 5 mm for fine aggregates in general-purpose concrete, was investigated. It was shown that replacing natural aggregates with converter slag increases the concrete grade strength, allowing cement consumption to be reduced by 31 %. Similar findings are reported in [5], where the partial (30 %) replacement of natural aggregates with EAF slag resulted in improved physical and mechanical properties of the concrete. The authors concluded that EAF slag can be used to produce environmentally friendly concrete. In [6], concrete mixtures with 30 % fly ash replacing cement and 50 % EAF slag replacing coarse aggregate were tested for their physical and mechanical properties. The results demonstrated that the strength characteristics of these concrete mixtures surpassed those of conventional concrete made entirely with cement and natural aggregates. In [7], researchers investigated the replacement of coarse natural aggregates with EAF slag, while retaining natural quartz sand as the fine aggregate. It was observed that concrete containing EAF slag exhibited a faster strength gain during the first seven days of curing compared to concrete made with natural aggregates. Although the rate of strength development subsequently declined, the final grade strength of the slag-containing concrete remained higher. In [8], it was shown that eco-concrete incorporating 5 % aluminum slag and 20 % EAF slag as substitutes for natural aggregates demonstrated strength and durability levels comparable to those of conventional concrete. A common feature across these studies is the use of slag primarily as a partial or complete replacement for natural aggregates, without altering the underlying mechanism of strength development based on Portland cement. However, this approach does not permit the complete elimination of Portland cement from the concrete mix, even though its production is a major source of CO2 emissions.

A promising strategy for fully replacing Portland cement in concrete and mortar formulations involves the use of alkali-activated slag binders. The theoretical foundation for such binders was established by V.D. Glukhovskii [9], who proposed introducing various alkaline additives into slags prior to grinding. Upon hydration, these binders form insoluble calcium and sodium aluminosilicate hydrates – zeolites – capable of achieving compressive strengths of up to 200 MPa. At present, most studies in this area focus on the alkali activation of blast furnace slag [10] and EAF slag in combination with other industrial wastes [11 – 13]. The primary drawback of these binders is the need for extremely fine slag grinding and the presence of free alkalis in fully cured concrete, which may migrate to the surface and cause severe efflorescence. This issue is addressed in geopolymer binders, where free alkalis generated during activation are chemically bound within a three-dimensional polymer network [14]. This is achieved through the addition of specially treated metakaolins. Once incorporated into the polymer structure, the alkalis are immobilized and no longer migrate to the surface, effectively preventing efflorescence formation.

Since EAF slag contains a significant amount of iron oxides, and its silicate component consists primarily of dicalcium silicate (β-2CaO·SiO2 ) and merwinite (3CaO·MgO·2SiO2 ) – which decomposes at elevated basicity into two molecules of dicalcium silicate and periclase – the authors explored the possibility of simultaneously producing pig iron and Portland cement. This was to be achieved by increasing the slag’s basicity through the addition of highly basic LF slag and extra lime. Laboratory studies and pilot-scale industrial trials confirmed the feasibility of this approach [15; 16]. It was established that mixing molten EAF slag, LF slag, and solid lime in a ratio of 64:17:17 %, respectively, allows for the simultaneous formation of Portland cement clinker and pig iron in proportions of 82 and 18 %, respectively. The Portland cement produced from this clinker demonstrated the following physical and mechanical properties:

– initial setting time – 175 min;

– final setting time – 285 min;

– volume stability – 0.2 mm;

– compressive strength after 2 days – 11.7 MPa;

– compressive strength after 28 days – 47.8 MPa.

According to GOST 31108, this cement meets the requirements for strength class 42.5 N. The chemical composition of the resulting pig iron complied with GOST 805 for foundry-grade pig iron of grade PL 1 and was as follows (wt. %: 3.13 С; 2.26 Mn; 0.109 Si; 0.036 P; 0.021 S.

Potential pathways for technology implementation

Despite the positive outcomes of the trials, implementing this technology would require a complete reconstruction of steelmaking facilities, including the establishment of a dedicated slag secondary treatment section and a full reorganization of the logistics involved in slag transportation and processing.

In light of these challenges, an alternative approach was explored – the sulfate activation of steelmaking slags to impart the properties of mineral binding agents. In the construction industry, certain types of specialty cements are widely used, particularly gypsum-alumina cements based on calcium sulfoaluminates [17] and calcium sulfosilicates [18]. Gypsum-alumina cements are commonly applied for road and infrastructure repairs and are also used in rapid-setting and waterproofing systems – for example, the Emaco2 line of fast-setting concretes was developed on the basis of such cements. Calcium sulfoaluminate and sulfoaluminoferrite binders are also well established in the production of expansive oil-well cements [19].

At present, several anhydrous minerals containing gypsum are known to possess strong binding properties. These include:

– calcium sulfosilicate (sulfospurrite 2(2СaO·SiО2 )·CaSO4 [17;18];

– calcium sulfoaluminate (yeelimite) 3(CaO·Al2O3)·CaSO4 [17];

– calcium sulfoferrites, including low-basic 3(CaO·Fe2O3)ˑCaSO4 and high-basic CaO·Fe2O3·CaSO4 [20];

– a group of calcium sulfoaluminoferrites with the general formula CaOn·(Al2O3 )m·(Fe2O3 )k·(SO3 )b [21].

These minerals are typically obtained by firing raw material mixtures at 1100 – 1300 °C, followed by either separate or joint grinding with Portland cement [17]. For EAF and LF slags, which contain mayenite (C12A7 ) as well as dicalcium silicates (β-2CaO·SiO2 and γ-2CaO·SiO2 ), sulfate activation can be achieved through joint grinding with natural gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O).

The authors initially applied sulfate activation to LF slags. To prevent the development of internal stresses during hydration of the resulting binder, which was produced by joint grinding of LF slag and gypsum, it was proposed to introduce additives that would enable the formation of a mineral binding agent following the principle of gypsum – cement – pozzolanic systems [22]. In this patented formulation, LF slag and gypsum act as the primary binder (cement), while pozzolanic additives include acidic sludges, various slags, and calcium carbonates – including EAF slag in amounts ranging from 9.5 to 23.0 %. The developed composite water-resistant gypsum-based binder made it possible to achieve compressive strengths in the range of 5 to 10 MPa in construction products.

Methodology for optimisation

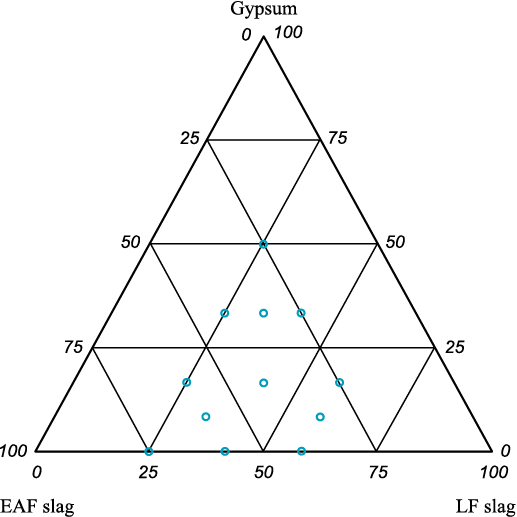

Further investigation of this binding system showed that increasing the proportion of EAF slag leads to a significant improvement in concrete strength. Notably, EAF slag can be added to the binder in the form of fine screening material (fraction 0 – 5 mm). Therefore, optimization of the strength properties of such concrete was carried out using experimental design methods, namely the simplex lattice method, with the test results described by a third-degree polynomial. The varying factors selected for the optimization were the contents of EAF slag, LF slag, and gypsum dihydrate in the raw mix. The intervals of variation for each factor are given in Table 1.

The scope of optimization is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1. Intervals of the factors variation

Fig. 2. Scope of optimisation | |||||||||||||||||

According to the experimental plan, raw mixtures were prepared and mixed with water at a water-to-solid ratio of 0.4:1. The concrete was poured into standard molds and cured under air-dry conditions for seven days. After this curing period, compressive strength was measured and used as the response function.

Results and discussion

The experimental plan and the results of compressive strength testing after 7 days are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Experimental plan and test results

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

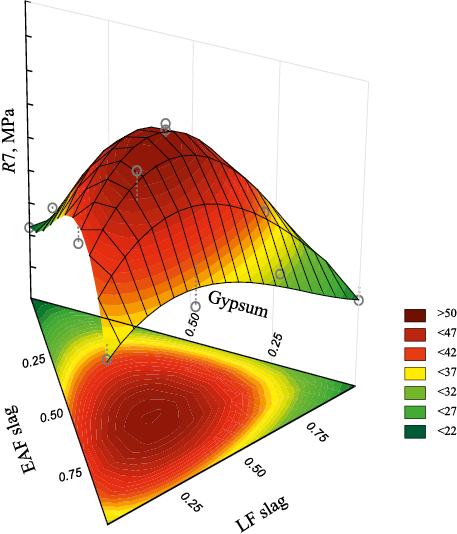

Fig. 3 shows the overall distribution of the response function for the compressive strength of the slag-based binder.

Fig. 3. General view of response function distribution |

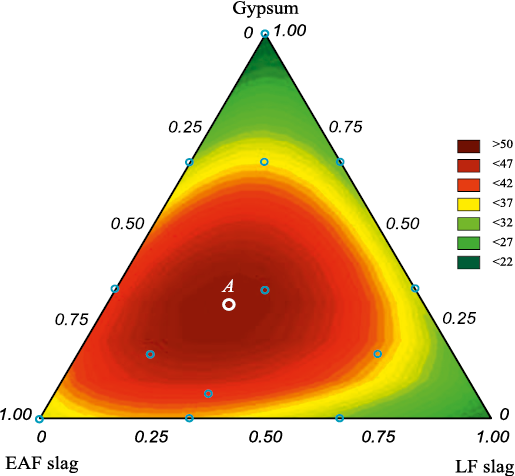

Fig. 4 presents the isolines of equal compressive strength for the slag-based bind.

Fig. 4. Isolines of equal compressive strength when compressing the binder |

Point A in Fig. 4 corresponds to the maximum compressive strength of the binder – 50.4 MPa – achieved at an EAF slag content of 42.0 %, LF slag content of 42.0 %, and gypsum dihydrate content of 16.0 %.

The results of testing mineral binding agents based on steelmaking slags formed under modern steel production conditions confirm the feasibility of processing these slags using alternative approaches to those currently in use. Instead of limiting slag processing to conventional crushing and size classification, it is proposed to use steelmaking slags as raw materials for producing dry construction and concrete mixes. These products offer significantly higher market value compared to classified slag gravel and sand. Such mixes can be manufactured at existing dry mix production facilities, requiring only minimal modifications to the slag handling sections of metallurgical plants.

Conclusions

Steelmaking slags generated during the steel smelting process contain hydraulically active phases that are capable of hardening upon contact with water. This study examined current methods for processing steelmaking slags and explored ways to impart the properties of mineral binding agents to them. A sulfate treatment method was proposed to activate the hydraulically active phases contained in the slags. As a result of sulfate activation, the resulting slag-based mineral binder exhibits high physical and mechanical properties, comparable to those of binders produced with Portland cement. It is recommended that this slag-based binder be used for the production of dry construction and concrete mixes suitable for both road building and general-purpose construction applications.

References

1. Smirnov L.A., Sorokin Yu.V., Snyatinovskaya N.M., Danilov N.I., Eremin A.Yu. Processing of Man-Made Waste (based on the materials of programs for processing man-made formations of the Sverdlovsk region). Yekaterinburg: UIPC; 2012:607. (In Russ.).

2. Sheshukov O.Yu., Mikheenkov M.A., Nekrasov I.V., Egiazar’yan D.K., Metelkin A.A., Shevchenko O.I. Issues of Utilization of Steelmaking Refining Slags. Nizhny Tagil: NTI (branch) of UrFU; 2017:208. (In Russ.).

3. Leont’ev L.I., Sheshukov O.Yu., Mikheenkov M.A., Nekrasov I.V., Egiazar’yan D.K. Technological features of processing steelmaking slags into building materials and products. Stroitel’nye materialy. 2014;(10):70–74. (In Russ.).

4. Costa L.C.B., Nogueira M.A., Ferreira L.C., Elói F.P.F., Carvalho J.M.F., Peixoto R.A.F. Eco-efficient steel slag concretes: An alternative to achieve circular economy. Revista IBRACON de Estruturas e Materiais. 2022;(15):e15201. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1983-41952022000200001

5. Diotti A., Cominoli L., Galvin A.P., Sorlini S., Plizzari G. Sustainable recycling of electric arc furnace steel slag as aggregate in concrete: Effects on the environmental and technical performance. Sustainability. 2021;13(2):521. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020521

6. Sekaran A., Palaniswamy M., Balaraju S. A study on suitability of EAF oxidizing slag in concrete: An eco-friendly and sustainable replacement for natural coarse aggregate. The Scientific World Journal. 2015;(1);1–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/972567

7. Nguyen T.T.H., Phan D.H., Mai H.H., Nguyen D.L. Investigation on compressive characteristics of steel-slag concrete. Materials. 2020;13(8):1928. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ma13081928

8. Javali S., Chandrashekar A.R., Naganna S.R., Manu D.S., Hiremath P., Preethi H.G., Kumar N.V. Eco-concrete for sustainability: utilizing aluminium dross and iron slag as partial replacement materials. Clean Technology and Environmental Policy. 2017;19:2291–2304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10098-017-1419-9

9. Glukhovskii V.D., Pakhomov V.A. Slag-Alkali Cements and Concretes. Kiev: Budivelnik; 1978:184. (In Russ.).

10. Artamonova A.V., Voronin K.M. Slag-alkaline binders based on blast-furnace granular slag of centrifugal impact grinding. Tsement i ego primenenie. 2011;(4):108–113. (In Russ.).

11. Peys A., White C.E., Rahier H., Blanpain B., Pontikes Y. Alkali-activation of CaO-FeOx-SiO2 slag: Formation mechanism from in situ X-ray total scattering. Cement and Concrete Research. 2019;122:179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2019.04.019

12. Peys A., White C.E., Rahier H., Blanpain B., Pontikes Y. Molecular structure of CaO-FeOx-SiO2 glassy slags and resultant inorganic polymers. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2018;101(12):5846–5857. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.15880

13. Sedira N., Castro-Gomes J. Effects of EAF-Slag on alkali-activation of tungsten mining waste: mechanical properties. MATEC Web of Conferences. 2019;274:01003. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201927401003

14. Dudnikov A.G., Dudnikova M.S., Redzhani A. Geopolymer concrete and its application. Stroitel'nye materialy, oborudovanie, tekhnologii XXI veka. 2018;(2):38–45. (In Russ.).

15. Mikheenkov M.A., Sheshukov O.Yu., Nekrasov I.V., Egiazar’yan D.K., Lobanov D.A. Production of mineral binder from steel-smelting slag. Steel in Translation. 2016;46: 232–235. https://doi.org/10.3103/S0967091216030098

16. Mikheenkov M.A., Sheshukov O.Yu., Nekrasov I.V. A method for processing steelmaking waste to produce Portland cement clinker and cast iron. Patent RF no. 2629424. MPK7 C21B 3/04. Bulleten’ izobretenii. 2017;(25). (In Russ.).

17. Kuznetsova T.V. Aluminate and Sulfoaluminate Cements. Moscow: Stroiizdat; 1986:208 (In Russ.).

18. Atakuziev T.A. Sulfomineral Cements based on Phosphogypsum. Tashkent: FAN; 1979:152. (In Russ.).

19. Vyakhirev V.I., Frolov A.A., Krivoborodov Yu.R. Expanding Grouting Cements. Moscow: IRC RAO Gazprom; 1998:52. (In Russ.).

20. Kuznetsova T.V., Sychev M.M., Osokin A.P. Special Cements. St. Petersburg: Stroiizdat Spb; 1997:314. (In Russ.).

21. Savchenko S.V. Sulfoaluminoferrite cements. Tsement. 1986;(3):11–12. (In Russ.).

22. Zuev M.V., Mamaev S.A., Mikheenkov M.A., Stepanov A.I. Composite waterproof gypsum binder. Patent RF no. 2505504. IPC7 C04B 28/14. Bulleten’ izobretenii. 2014;(3). (In Russ.).

About the Authors

О. Yu. SheshukovRussian Federation

Oleg Yu. Sheshukov, Chief Researcher of the Laboratory of Powder, Composite and Nano-Materials, Institute of Metallurgy, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences; Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Prof., Director of the Institute of New Materials and Technologies, Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin

101 Amundsena Str., Yekaterinburg 620016, Russian Federation

19 Mira Str., Yekaterinburg 620002, Russian Federation

M. A. Mikheenkov

Russian Federation

Mikhail A. Mikheenkov, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Senior Researcher of the Laboratory “Pyrometallurgy of Ferrous Metals”, Institute of Metallurgy, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences; Prof., Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin

101 Amundsena Str., Yekaterinburg 620016, Russian Federation

19 Mira Str., Yekaterinburg 620002, Russian Federation

D. К. Egiazar’yan

Russian Federation

Denis K. Egiazar’yan, Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Senior Researcher, Head of the Laboratory of Technogenic Formations Problems, Institute of Metallurgy, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences; Assist. Prof. of the Chair of Metallurgy of Iron and Alloys, Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin

101 Amundsena Str., Yekaterinburg 620016, Russian Federation

19 Mira Str., Yekaterinburg 620002, Russian Federation

А. M. Mikheenkov

Russian Federation

Aleksandr M. Mikheenkov, Postgraduate of the Chair “Metallurgy of Iron and Alloys”

19 Mira Str., Yekaterinburg 620002, Russian Federation

M. V. Kleonovskii

Russian Federation

Mikhail V. Kleonovskii, Engineer of the Chair “Metallurgy of Iron and Alloys”

19 Mira Str., Yekaterinburg 620002, Russian Federation

O. V. Matyukhin

Russian Federation

Oleg V. Matyukhin, Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Assist. Prof. of the Chair “Thermal Physics and Informatics in Metallurgy”

19 Mira Str., Yekaterinburg 620002, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Sheshukov О.Yu., Mikheenkov M.A., Egiazar’yan D.К., Mikheenkov А.M., Kleonovskii M.V., Matyukhin O.V. Peculiarities of the phase composition formation of steelmaking slags and evaluation of the possibility of obtaining mineral binders with low CO2 generation on their basis. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(2):179-187. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-2-179-187