Scroll to:

On the influence of rare-earth oxide additives on kinetics of borated layer formation and boron diffusion along grain boundaries during steel boriding

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-2-148-157

Abstract

Metallographic studies showed that the use of rare-earth oxide (REO) additives during liquid electrolysis-free boriding increases the borated layers depth, with these additives not interacting with the treated product material. Addition of lanthanum and yttrium oxides increases the borated layer depth by 30 – 40 %, while addition of scandium oxide either has no effect or decreases the layer depth. X-ray phase analysis of boriding alloys with REO additives was conducted in this study. It was shown that REO additions to the melt result in formation of low-melting rare-earth borates (LaBO3 , YBO3 , ScBO3 ), which enhance grain boundary diffusion and significantly intensify the boriding process. Estimated values of bulk and grain boundary diffusion coefficients were obtained. The addition of yttrium oxide increased the bulk diffusion coefficient in VKS-5 steel by 280 %. In Kh12MF steel, addition of lanthanum oxide resulted in an 83 % increase in the bulk diffusion coefficient. For 40Kh steel, no increase in the bulk diffusion coefficient was recorded in any of the investigated cases. The grain boundary diffusion coefficient increased in VKS-5 and Kh12MF steels by 1000 % with addition of lanthanum oxide. Addition of yttrium oxide increased the grain boundary diffusion coefficient by 1000 % in VKS-5 steel, by 135 % in Kh12MF steel, and by 87 % in 40Kh steel. Addition of scandium oxide increased the grain boundary diffusion coefficient by 160 % in VKS-5 steel. The diffusion coefficient values at grain boundaries obtained through modeling calculations agree well with the experimental data.

Keywords

For citations:

Ishmametov D.A., Pomel’nikova A.S., Petelin A.L. On the influence of rare-earth oxide additives on kinetics of borated layer formation and boron diffusion along grain boundaries during steel boriding. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(2):148-157. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-2-148-157

Introduction

Although the use of rare-earth metal (REM) additives in liquid boriding increases the depth of borated layers, promotes the formation of complex borides, and improves mechanical properties [1; 2], their application has not become widespread in boriding technologies due to the high cost of such additives. Recent studies on the use of rare-earth oxide (REO) additives in powder boriding [3 – 5] have shown that they produce similar effects. Research into REO additives in liquid electrolysis-free boriding has demonstrated an increase in the depth of borated layers and, in some cases, changes in their morphology [6; 7]. It has been noted that REO additives do not interact with the material being treated and instead act as catalysts in the boriding process [8; 9].

A key factor in controlling the boriding process when using REO additives is understanding the mechanism by which they influence the kinetics of borated layer formation and boron diffusion into the metal [10 – 12].

Although no traces of rare-earth elements are detected in the structure of the treated steels, their presence in the melt can affect the boriding process in several ways [13 – 14].

• Rare-earth oxides may act as catalysts that accelerate chemical reactions in the melt. This can lead to an increased rate of formation of active boron atoms, which diffuse into the steel and ultimately result in deeper borated layers.

• The presence of REO additives alters the physicochemical properties of the melt, such as viscosity, surface tension, and ion distribution. These changes may promote more uniform and active interaction between boron and the steel surface, enhancing boron penetration depth.

• REO additives may influence the structure and defectiveness of the oxide layer on the steel surface, facilitating more active diffusion of boron atoms into the metal.

• Rare-earth oxides can affect the formation of intermediate phases in the melt or at the steel–melt interface, thereby intensifying the boriding process.

A study reported in the international literature [15] describes the positive effect of cerium oxide addition on the depth of borated layers produced on a Ti6Al4V titanium alloy. The beneficial effect is attributed to the formation of low-melting rare-earth borates, which enhance the transport capacity of the boriding agent. However, that study focuses solely on powder boriding and does not consider the contribution of low-melting RE borate phases to grain boundary diffusion of boron into the material.

The aim of this study is to analyze the effect of rare-earth oxide additives on boron diffusion during the formation of borated layers in steels with different compositions.

Materials and methods

The steel samples were subjected to liquid electrolysis-free boriding in a melt composed of sodium tetraborate and boron carbide, with lanthanum, yttrium, or scandium oxides added in amounts of 1, 5, 10, and 20 wt. %. The boriding process was conducted at 1000 °C for 8 h, followed by air cooling of the samples.

This study investigated VKS-5, Kh12MF, and 40Kh steels, selected for their varying carbon content and alloying element composition. Their chemical compositions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Chemical composition of the studied steels

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The microstructure of the samples was examined using a Jeol JXA-iSP100 electron probe microanalyzer. Microstructure images were obtained with a backscattered electron detector.

X-ray phase analysis of the boriding alloy was performed using a BRUKER D2 PHASER X-ray diffractometer.

Results and discussion

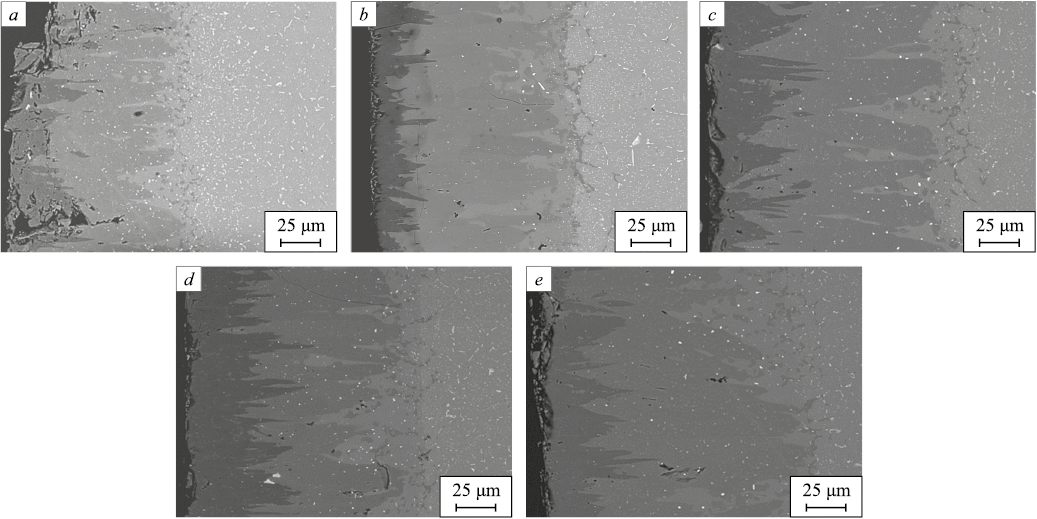

As previously shown, the addition of rare-earth oxides has a significant impact on the depth, properties, and, in some cases, the morphology of the resulting borated layers. All steel samples treated in the various melts described in this study were examined using an electron microscope. Fig. 1 presents the microstructures of borated layers formed on VKS-5 steel in a standard melt and in melts containing 1, 5, 10, and 20 wt. % lanthanum oxide. These images were selected as they clearly illustrate the characteristic features of borated layer formation during liquid boriding with REO additives.

Fig. 1. Microstructure of borated layers on VKS-5 steel: |

As seen in Fig. 1, the addition of 1 wt. % lanthanum oxide promotes the formation of higher-quality borated layers. With 5 wt. % lanthanum oxide, the penetration depth of the dark, boron-rich FeB phase increases, although this phase forms unevenly. Increasing the additive content to 10 wt. % leads to even deeper FeB penetration, with the dark phase displaying greater continuity. Notably, the deepening zone of the borated layer consists of light, acicular regions that appear as a continuation of the dark layer. This zone reflects the initial accelerated diffusion of boron along the grain boundaries of the matrix, followed by boron penetration into the grain volume from the boundaries, which act as diffusion sources. However, as the diffusant concentration at the boundaries decreases beyond a certain depth, the grains are no longer fully saturated with boron, resulting in a jagged interface at the bottom of the borated layer. Boron partially decorates the grain boundaries, which become visible in the transition to the underlying structure. A network of boride phases along the grain boundaries in the transition zone is observed in all the presented microstructures.

Table 2 presents the data on the depth of borated layers formed in melts with various additives for the steels studied.

Table 2. Depth data of borated layers in melts with various additives on steels

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Analysis of the data in Table 2 indicates that rare-earth oxide additives influence the depth of the borated layers. However, there appears to be a critical concentration of these additives, beyond which the boriding process slows down and the layer depth decreases. Notably, the addition of scandium oxide does not result in any increase in layer depth. The chemical composition of the steel also plays a significant role in determining the depth of borated layers formed in melts without additives. While previous studies [6; 18] have identified carbon content as the primary factor influencing layer depth, the data in Table 1 show no clear correlation. For example, the low-carbon VKS-5 steel exhibited a layer depth of 120 – 130 µm; the medium-carbon 40Kh steel reached 240 – 250 µm; whereas the high-carbon Kh12MF steel showed a depth of only 95 – 105 µm.

Given that the addition of 5 wt. % rare-earth oxide (REO) consistently resulted in increased borated layer depth, the compositions of melts containing 5 wt. % REO were analyzed in detail.

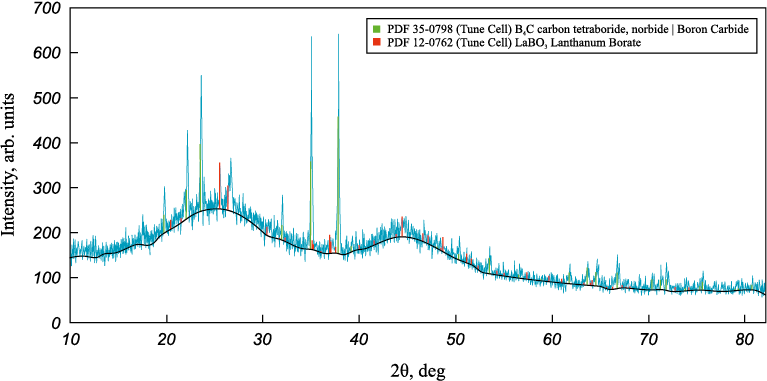

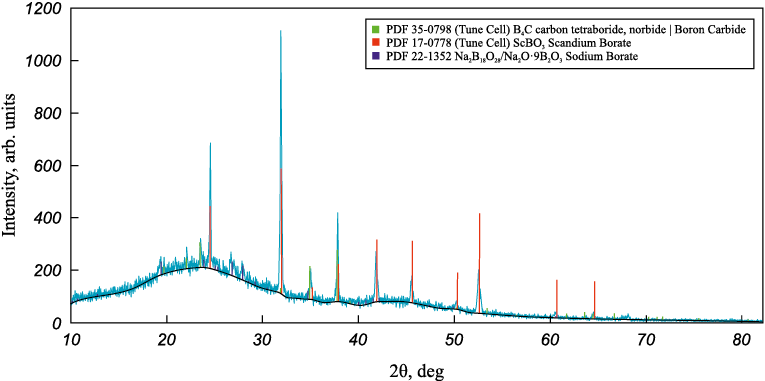

Figs. 2 – 4 show the X-ray diffraction patterns of boriding melts with various REO additives.

Fig. 2. Diffraction pattern of the melt with 5 wt. % lanthanum oxide addition

Fig. 3. Diffraction pattern of the melt with 5 wt. % yttrium oxide addition

Fig. 4. Diffraction pattern of the melt with 5 wt. % scandium oxide addition |

These diffraction patterns reveal the formation of a new phase in all melts – rare-earth borates (LaBO3 , YBO3 , ScBO3 ). According to previous studies [14 – 16], these compounds are low-melting. It was also observed during melt preparation that adding up to 10 wt. % REO improved melt fluidity.

X-ray phase analysis suggests that the presence of a low-melting phase in the melt increases its fluidity and likely promotes faster diffusion of boron atoms into the steel. Given that the boriding temperature is 1000 °C – within the range where grain boundary diffusion dominates over bulk diffusion (Т < 0.7Тm [17]) – it can be assumed that boron initially diffuses rapidly along grain boundaries (GB), followed by penetration into the grain interiors from these boundaries, which serve as diffusion sources. This is due to the fact that the activation energy for grain boundary diffusion is considerably lower than for bulk diffusion, making it the preferred pathway under these conditions. This assumption is supported by the observed morphology of the borated layers – specifically, the presence of light acicular regions within the layer and a boride network along grain boundaries in the transition zone.

It is also reasonable to hypothesize that the low-melting RE borate phase acts as a transport medium, enhancing the delivery of boron atoms to grain boundary outlets at the matrix surface. Grain boundary diffusion, being faster than bulk diffusion, creates leading boron fluxes into the steel. This results in a higher concentration of boron in the reaction zone, thereby accelerating the boriding process.

In light of the presumed substantial role of REO additives in promoting grain boundary diffusion, it is appropriate to assess the depth of boron penetration for different melt compositions and to estimate the bulk and grain boundary diffusion coefficients of boron in the studied steels.

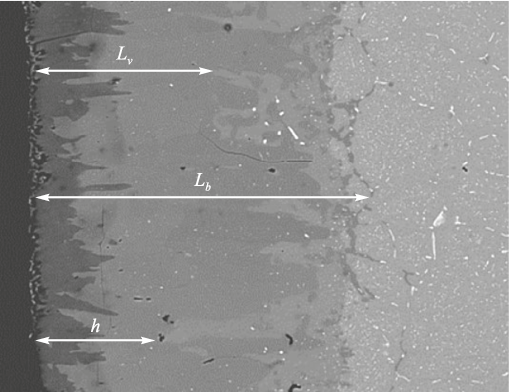

Based on the metallographic analysis, the following characteristic depths were determined.

• h – the depth of the borated layer where bulk diffusion is the dominant mechanism. In this zone, boron enrichment occurs primarily through lattice diffusion, as the supply of boron atoms to the grain boundaries (GBs) is limited and no low-melting transport medium is present. The contribution of grain boundary diffusion in this region is minimal or absent, and the boron distribution is governed solely by bulk diffusion.

• Lb – the grain boundary diffusion path, defined as the distance from the sample surface to the depth where boron enrichment along grain boundaries significantly decreases (approximately by a factor of e).

• Lv – the bulk diffusion path of boron during the saturation of grain interiors from the grain boundaries, which act as sources of boron atoms – that is, in the presence of grain boundary diffusion fluxes.

Fig. 5 illustrates the zones within the borated layer corresponding to these parameters.

Fig. 5. Structure of the borated layer with marked depths h, Lb , Lv |

The bulk diffusion coefficient of boron in the steels was estimated using the equation provided in [18]:

| \[h = \sqrt {D\tau } ,\] | (1) |

where h is the layer depth, µm; D is the bulk diffusion coefficient of boron, m2/s; τ is the boriding time, s.

Table 3 summarizes the average values of h, Lb , Lv obtained from metallographic observations.

Table 3. Average values of h, Lb , Lv , D for all studied borated layers

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Analysis of the data in Table 3 shows that rare-earth oxide (REO) additives significantly affect the depth of the borated layers. In VKS-5 steel, which has a fine-grained structure (approximately 5 – 8 µm), grain boundary diffusion contributes most prominently – particularly with the addition of yttrium and lanthanum oxides – reflected in the increased Lb values. Kh12MF steel, with a slightly larger grain size (8 – 12 µm), demonstrates similar trends, though the effect is less pronounced. In contrast, 40Kh steel, with coarser grains (12 – 18 µm), shows the weakest response to REO additions. These findings confirm that fine-grained structures enhance grain boundary diffusion, while in steels with larger grains, bulk diffusion plays a more dominant role in borated layer formation.

To predict the kinetics of borated layer formation during liquid boriding with REO additions, estimated calculations of the grain boundary diffusion coefficient (Db ) can be performed. The Lb values can also be estimated using the formulas proposed in [19; 20] and compared with experimental values obtained through microstructural analysis. This comparison helps validate the reliability of the grain boundary diffusion coefficients derived from the experimental data.

An estimated calculation of Lb was performed using Equation (2), as proposed in [19; 20], with Lv and D values taken from Table 2. The average grain sizes were 5 – 8 µm for VKS-5 steel, 8 – 12 µm for Kh12MF steel, and 12 – 18 µm for 40Kh steel:

| \[{L_v} = {L_b}\left[ {1 + \ln \left( {1 - \frac{4}{\pi }{e^{ - \frac{{{\pi ^2}D\tau }}{{{l^2}}}}}} \right)} \right],\] | (2) |

where l is the grain size, µm.

Table 4 presents the Lb values obtained through estimated calculations using Equation (2) (Lb.calc ), alongside those determined through microstructural analysis (Lb.exp ).

Table 4. Значения Lb.расч и Lb.эксп

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The comparison shows that the calculated diffusion lengths closely match the experimental data, with deviations not exceeding 12 %. This consistency supports the reliability of the calculation method and validates the experimental findings.

Using Equation (3), proposed in [19; 20], and the Lb values from Table 3, the grain boundary diffusion coefficient (Db ) can be estimated:

| \[{L_b} = \sqrt {\frac{{{D_b}\delta l}}{{8D}}{e^{\frac{{{\pi ^2}D\tau }}{{{l^2}}}}}} ,\] | (3) |

where δ is the interatomic spacing, nm, used to estimate the average grain boundary thickness.

The estimated grain boundary diffusion coefficients are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. Оценочные значения коэффициентов диффузии по ГЗ

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Analysis of the data in Table 5 shows that the calculated grain boundary diffusion coefficients are generally in good agreement with the experimental values, confirming the adequacy of the chosen calculation approach. In all the steels studied – particularly in VKS-5 – an increase in boron penetration into the matrix was observed with the addition of lanthanum and yttrium oxides.

Conclusions

The structure of borated layers formed in melts containing 5, 10, and 20 wt. % of lanthanum, yttrium, and scandium oxides was investigated. The depth of the resulting layers was measured. It was found that additions of lanthanum and yttrium oxides significantly increase the depth of the borated layers, whereas scandium oxide either has no effect or reduces the layer depth.

X-ray phase analysis revealed the formation of low-melting rare-earth borates (LaBO3 , YBO3 , ScBO3 ) in the boriding melts. These phases improve the fluidity of the melt, facilitating more efficient transport of boron atoms to the grain boundaries and enhancing their delivery into the steel. This leads to higher boron concentrations within the grains and plays a key role in forming deeper and more uniform borated layers.

Estimated values of both bulk and grain boundary diffusion coefficients were obtained. The addition of yttrium oxide increased the bulk diffusion coefficient in VKS-5 steel by 280 %. In Kh12MF steel, lanthanum oxide led to an 83 % increase. In 40Kh steel, no increase in the bulk diffusion coefficient was recorded in any of the studied cases. The addition of lanthanum oxide resulted in a 1000 % increase in the grain boundary diffusion coefficient in VKS-5 and Kh12MF steels. The addition of yttrium oxide resulted in a 1000 % increase in grain boundary diffusion in VKS-5 steel, 135 % in Kh12MF, and 87 % in 40Kh. The addition of scandium oxide led to a 160 % increase in grain boundary diffusion in VKS-5.

VKS-5 steel exhibited the strongest response to REO additions, attributed to its fine-grained structure and the dominant role of grain boundary diffusion. In Kh12MF steel, which has a medium grain size, the effect was noticeable but less pronounced. In 40Kh steel, which has a coarser grain structure, REO additions in some cases contribute to an increase in boriding depth, although bulk diffusion remains significant.

The grain boundary diffusion coefficients obtained through modeling were in good agreement with experimental values, confirming the reliability of the calculation methods and their suitability for modeling diffusion processes in steels.

References

1. Dozmorov S.V., Bakhmat V.V., Antipov I.A., Lozmorova E.V., Brynskii A.A., Kopachev V.Ya. Composition for boriding steel products from melt. Patent SU no. 1617046. MPK C23C 8/44. Bulleten’ izobretenii. 1990;(48). (In Russ.).

2. Kovalevskii A.V., Prismotrov E.P., Savel’ev Yu.D., Soroka V.V. Melt for boriding steel products. Patent SU no. 1093727. MPK C23C 8/44. Bulleten’ izobretenii. 1984;(19). (In Russ.).

3. Mei S., Zhang Y., Zheng Q., Fan Y., Lygdenov B., Guryev A. Compound boronizing and its kinetics analysis for H13 steel with rare earth CeO2 and Cr2O3 . Applied Sciences. 2022;12(7):3636. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12073636

4. Zhang Y.W., Zheng Q., Fan Y., Mei S.Q., Lygenov B., Guryev A. Effects of CeO2 content, boronizing temperature and time on the microstructure and properties of boronizing layer of H13 steel. Materials for Mechanical Engineering. 2021;45(7):22–26. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.45.22

5. Santaella C.R.K., Cotinho S.P., Correa O.V., Pillis M.F. Enhancement of the RE-boronizing process through the use of La, Nd, Sm, and Gd compounds. Journal of Engineering Research. 2022;2(14):2–7. https://doi.org/10.22533/at.ed.3172142206074

6. Ishmametov D.A., Pomel’nikova A.S. Study of structure and properties of borated layers obtained on steels with different alloying elements by method of liquid electrolysis-free borating in melt with addition of yttrium oxide. Zagotovitel'nye proizvodstva v mashinostroenii. 2023;21(11):511–520. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.36652/1684-1107-2023-21-11-511-520

7. Ishmametov D.A., Pomelnikova A.S., Rumyantseva S.B. Effect of lanthanum oxide on structure and properties of borated layers obtained on low-carbon complex-alloyed steel. Tekhnologiya metallov. 2024;(5):2–9. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.31044/1684-2499-2024-0-5-2-9

8. Ishmametov D.A., Pomel’nikova A.S., Rumyantseva S.B. Study of effect of lanthanum oxide on kinetics, morphology and properties of borated layers obtained by liquid method on different carbon content steels. Uprochnyayushchie tekhnologii i pokrytiya. 2024;20(4):174–180. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.36652/1813-1336-2024-20-4-174-180

9. Greco A., Mistry K., Sista V., Eryilmaz O., Erdemir A. Friction and wear behaviour of boron-based surface treatment and nano-particle. Wear. 2011;271(9–10):1754–1760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2010.11.060

10. Lin N., Zhou P., Zhou H., Guo J., Zhang H., Zou J., Ma Y., Han P., Tang B. Pack boronizing of P110 oil casing tube steel to combat wear and corrosion. International Journal of Electrochemical Science. 2015;10(3):2694–2706. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1452-3981(23)04878-2

11. Wang D., Li Y.D., Zhang X.L. A novel steel RE-borosulphurizing and mechanical properties of the produced RE-borosulfide layer. Applied Surface Science. 2013;276:236–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.03.094

12. Chapter 12 – Steel Transformations. In: Modern Physical Metallurgy. 8th ed. Smallman R.E., Ngan A.H.W. eds. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2014:473–498.

13. Kulka M. Trends in thermochemical techniques of boriding. In: Current Trends in Boriding. Cham: Springer; 2019:17–98.

14. Agarwal S., Kim H.I., Park K., Lee J.Y. Thermodynamic aspects for rare earth metal production. In: Rare Metal Technology 2020. Springer; 2020:39–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38106-6_3

15. Yuan K. A study on RE boronizing process in a titanium alloy. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology. 2021;30(4): 977–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-021-01157-3

16. Liu Y.H. Study on the solid boronizing agents, boronizing process, microstructure and properties of titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V): PhD thesis. Jiangsu University; 2013.

17. Bokshtein B.S., Bokshtein S.Z., Zhukhovitskii A.A. Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Diffusion in Solids. Moscow: Metallurgiya; 1974:280. (In Russ).

18. Krukovich M.G., Prusakov B.A., Sizov I.G. Plasticity of Borated Layers. Moscow: Fizmatlit; 2010:384. (In Russ.).

19. Petelin A.L., Plohih A.I. The model of the layer boundary diffusion in multilayer materials. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2015;56(11):45–48. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2013-11-45-48

20. Polikevich K.B., Petelin A.L., Plokhikh A.I., Fomina L.P. Nitrogen diffusion along the layer boundaries after nitriding of multilayer materials. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2024;67(3):318–324. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-3-318-324

About the Authors

D. A. IshmametovRussian Federation

Dmitrii A. Ishmametov, Postgraduate of the Chair “Materials Science”, Bauman Moscow State Technical University; Head of the Laboratory, Federal State Research and Design Institute of Rare Metal Industry

5/1 Baumanskaya 2-ya Str., Moscow 105005, Russian Federation

2, bld. 1 Ehlektrodnaya Str., Moscow 111141, Russian Federation

A. S. Pomel’nikova

Russian Federation

Alla S. Pomel’nikova, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Prof. of the Chair “Materials Science”

5/1 Baumanskaya 2-ya Str., Moscow 105005, Russian Federation

A. L. Petelin

Russian Federation

Aleksandr L. Petelin, Dr. Sci. (Phys.–Math.), Prof., Bauman Moscow State Technical University; Prof. of the Chair of Physical Chemistry, National University of Science and Technology “MISIS”

5/1 Baumanskaya 2-ya Str., Moscow 105005, Russian Federation

4 Leninskii Ave., Moscow 119049, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Ishmametov D.A., Pomel’nikova A.S., Petelin A.L. On the influence of rare-earth oxide additives on kinetics of borated layer formation and boron diffusion along grain boundaries during steel boriding. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2025;68(2):148-157. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2025-2-148-157