Scroll to:

Thermodynamic aspects of WO3 tungsten oxide reduction by carbon, silicon, aluminum and titanium

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-4-449-456

Abstract

The development and research of new materials for machine parts of the mining and metallurgical complex by the method of surfacing with flux cored wire has a lot of attention nowadays. Flux cored wires are widely used for surfacing of steels with high wear resistance, in which reduced tungsten in the form of ferroalloys, ligatures and metal powder of various degrees of purity are used as fillers. However, due to the scarcity and high cost of tungsten, its rational use is an urgent task. For practical application, the technology of surfacing with tungsten-containing flux cored wire is of interest; using it the maximum extraction of tungsten into the deposited layer is achieved due to reduction processes in the arc. In order to increase the beneficial use of tungsten, the technologies of indirect alloying with tungsten during surfacing under the flux of flux cored wires, in which tungsten oxide is used as a filler on the one hand, and reducing agent – on the other, deserve consideration. It can be expected that during arc discharge, tungsten and (or) chemical compounds of tungsten with reducing agents can be formed during the surfacing process. This paper presents the results of a comparative analysis of the thermodynamic processes of tungsten oxide reduction by carbon, silicon, aluminum and titanium during arc discharge occurring during surfacing with flux cored wires under a layer of flux. The thermodynamic analysis of 41 reactions in standard states showed that the presence of reducing agents (carbon, silicon, aluminum, titanium) in the flux cored wire used for surfacing will contribute to the formation of silicides and tungsten carbides, and, possibly, tungsten itself. It was determined that the best state for the participation of tungsten oxide in reactions in the arc is WO3(g) gaseous state.

Keywords

For citations:

Bashchenko L.P., Bendre Yu.V., Kozyrev N.A., Mikhno A.R., Shurupov V.M., Zhukov A.V. Thermodynamic aspects of WO3 tungsten oxide reduction by carbon, silicon, aluminum and titanium. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2024;67(4):449-456. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-4-449-456

Introduction

For over 40 years, the use of surfacing with welding flux cored wire has been widely adopted. Combining this with advanced surfacing methods allows for solving complex technological challenges at a fundamentally new level [1 – 3].

Developing technology for applying wear-resistant surfacing involves several key stages: analyzing the nature of the part’s wear; assessing the weldability of the structural material and the permissible changes in the part’s geometry due to the thermal effects of surfacing; selecting a wear-resistant alloy; choosing a surfacing method; and developing surfacing regimes [4 – 8].

Recently, particular attention in manufacturing flux cored wire has been given to selecting charge materials [9 – 11]. One component of these charge materials is tungsten powder. Tungsten coatings are noted for their high wear resistance under “metal-to-metal” friction at elevated temperatures, as well as good heat and thermal resistance. They are mainly used in metallurgy and mechanical engineering for surfacing hot rolling rolls, hot cutting knives for metal, hot rolling stamps, and similar applications [12 – 15]. However, due to the high cost of pure powder and the absence of domestic manufacturers of this component within the Russian Federation, proposals have arisen to replace “pure” tungsten powder with tungsten oxide [16 – 18].

This work aims to conduct a comparative thermodynamic assessment of the likelihood of the reduction processes of tungsten oxide (WO3 ) by carbon, silicon, aluminum, and titanium during the arc discharge that occurs when surfacing with flux-cored wires under a layer of flux.

Materials and methods

A thermodynamic assessment was conducted to evaluate the likelihood of the following reactions:

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 2C(s, l) = 2/3W(s, l) + 2CO(g); | (1) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 2C(s, l) = 2/3W(s, l) + 2CO(g); | (1a) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + C(s, l) = 2/3W(s, l) + CO2 (g); | (2) |

| 1/3WO3(s, l) + CO(g) = 1/3W(s, l) + CO2 (g); | (3) |

| W(s, l) + C(s, l) = WC(s, l); | (4) |

| W(s, l) + 1/2C(s, l) = 1/2W2C(s, l); | (5) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 5/3C(s, l) = 2/3WC(s, l) + CO2 (g); | (6) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 4/3C(s, l) = 1/3W2C(s, l) + CO2 (g); | (7) |

| 1/4WO3(s, l) + 5/4CO(g) = 1/4WC(s, l) + CO2 (g); | (8) |

| 2/7WO3(s, l) + 8/7CO(g) = 1/7W2C(s, l) + CO2 (g); | (9) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 8/3C(s, l) = 2/3WC(s, l) + 2CO(g); | (10) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 7/3C(s, l) = 1/3W2C(s, l) + 2CO(g); | (11) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + Si(s, l) = SiO2(s, l) + 2/3W(s, l); | (12) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 7/3Si(s, l) = SiO2(s, l) + 2/3WSi2(s, l); | (13) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 21/15 Si(s, l) = SiO2(s, l) + 2/15W5Si3(s, l); | (14) |

| W(s, l) + 2Si(s, l) = WSi2(s, l); | (15) |

| W(s, l) + 3/5Si(s, l) = 1/5W5Si3(s, l); | (16) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 2Si(s, l) = 2SiO(g) + 2/3W(s, l); | (17) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 2Si(s, l) = 2SiO(g) + 2/3W(s, l); | (17a) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 10/3Si(s, l) = 2SiO(g) + 2/3WSi2(s, l); | (18) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 36/15 Si(s, l) = 2SiO(g) + 2/15W5Si3(s, l); | (19) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 4/3Al(s, l) → 2/3W(s, l) + 2/3Al2O3(s, l); | (20) |

| 2/3WO3(l) + 4/3Al(s, l) → 2/3W(s, l) + 2/3Al2O3(s, l); | (21) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 4/3Al(s, l) → 2/3W(s, l) + 2/3Al2O3(s, l); | (22) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 4/3Al(l) → 2/3W(s, l) + 2/3Al2O3(s, l); | (23) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 4/3Al(g) → 2/3W(s, l) + 2/3Al2O3(s, l); | (24) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 2/3Al2(g) → 2/3W(s, l) + 2/3Al2O3(s, l); | (25) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 4/3Al(g) → 2/3W(l) + 2/3Al2O3(s, l); | (26) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 4/3Al(g) → 2/3W(g) + 2/3Al2O3(s, l); | (27) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 4/3Al(g) → 2/3W(s, l) + 2/3Al2O3(l); | (28) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 2Al(g) → 2/3W(s, l) + 2AlO(g); | (29) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + Al(g) → 2/3W(s, l) + AlO2(g); | (30) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 4Al(g) → 2/3W(s, l) + 2Al2O(g); | (31) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 2Al(g) → 2/3W(s, l) + Al2O2(g); | (32) |

| 2/3WO3(g) + 2Al2(g) → 2/3W(s, l) + 2Al2O(g); | (33) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 2Ti(s, l) = 2/3W(s, l) + 2TiO(s, l); | (34) |

| 2/3WO3(h) + 2Ti(s, l) = 2/3W(s, l) + 2TiO(s, l); | (34a) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 4/3Ti(s, l) = 2/3W(s, l) + 2/3Ti2O3(s, l); | (35) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 6/5Ti(s, l) = 2/3W(s, l) + 2/5Ti3O5(s, l); | (36) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + 8/7Ti(s, l) = 2/3W(s, l) + 2/7Ti4O7(s, l); | (37) |

| 2/3WO3(s, l) + Ti(s, l) = 2/3W(s, l) + TiO2(s, l). | (38) |

The necessary thermodynamic characteristics of reactions (1) – (38) for the comparative assessment of the reductive properties of carbon, silicon, aluminum, and titanium with respect to tungsten oxide WO3 in standard conditions [∆r Н°(Т), ∆r S°(Т), ∆r G°(Т)] for reactants in solid crystalline (s), liquid (l), and gaseous (g) states, depending on temperature, were calculated using well-known methods [19]. These calculations were performed over the temperature range of the welding arc (1500 – 3500 K) based on the thermodynamic properties [[Н°(Т) – Н°(298,15 К)], S°(Т), ∆f H°(298,15 К)] of the WO3 , W, C, CO, CO2 , Si, SiO, SiO2 ,WSi2 , W5Si3 , Al, Al2 , Al2O3 , AlO, AlO2 , Al2O, Al2O2 , Ti, TiO, Ti2O3 , Ti3O5 , Ti4O7 , TiO2 . The calculations used data from reference books [19; 20], and all reactions were written for 1 mole of oxygen.

In the temperature range of 1500 – 3500 K, the following phase transitions (melting, boiling) occur: WO3 (1745 K), W2C (3008 K), WC (3058 K), W5Si3 (2623 K), Si (1685 K), SiO2 (1696 K), Al (2791 K), Al2O3 (2327 K), Ti (1939 K), TiO (2023 K), Ti2O3 (2115 K), Ti3O5 (2050 K), Ti4O7 (1950 K), TiO2 (2130 K).

Results and discussion

Among the solid crystalline reductants considered, aluminum has the lowest melting point. After melting, it is also expected to vaporize most easily.

To evaluate the potential impact of tungsten oxide (WO3 ) evaporation in the arc on the thermodynamic properties of the reactions, we calculated the thermodynamic characteristics of 15 reactions. In these reactions, tungsten oxide was considered to be in its gaseous state (WO3 (g)) (reactions 1а, 17а, 22 – 33, 34а).

Reactions (4), (5), and (15), (16) are not reactions that reduce tungsten oxide. Comparing their thermodynamics with those of reactions (6), (7) and (13), (14) respectively, shows a lower likelihood of forming tungsten carbides and silicides from the direct interaction of tungsten with carbon (4), (5) and silicon (15), (16) than from the reduction of tungsten oxide by carbon (6), (7) or silicon (13), (14).

The standard Gibbs energies of all 41 reactions, grouped by the type of reductant and temperature, are presented in the Table. The results and specific conclusions regarding the effectiveness of each reductant (carbon, silicon, aluminum, titanium) are discussed in studies [21 – 23]. Compared to the work [23], the reactions (34) – (38) for the reduction of WO3 by titanium in this study are written for 1 mole of oxygen (O2 ), not for 1 mole of Ti.

Standard Gibbs energies of reactions (1) – (38) depending on temperature

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The next step was to select the most effective reductants and the optimal conditions for these reactions.

It is known that the partial derivative of the standard Gibbs energy of a reaction with respect to temperature at constant pressure equals the standard entropy of the reaction with an opposite sign:

| \[{\left( {\frac{{\partial {\Delta _r}G^\circ (T)}}{{\partial T}}} \right)_{\rm{р}}} = - {\Delta _r}S^\circ (T).\] | (39) |

From this equation, it follows that the nature of the change in the standard Gibbs energy of a reaction with temperature is determined by the sign of the reaction’s standard entropy. In this context \(S_{\rm{g}}^{\rm{o}} > S_{\rm{l}}^{\rm{o}} > S_{{\rm{s}}}^{\rm{o}}\) for the same substance. Since the reactions (1) – (38) involve substances in all three physical states, many reactions exhibit significant changes in ∆r G°(T) depending on the temperature, both decreasing and increasing.

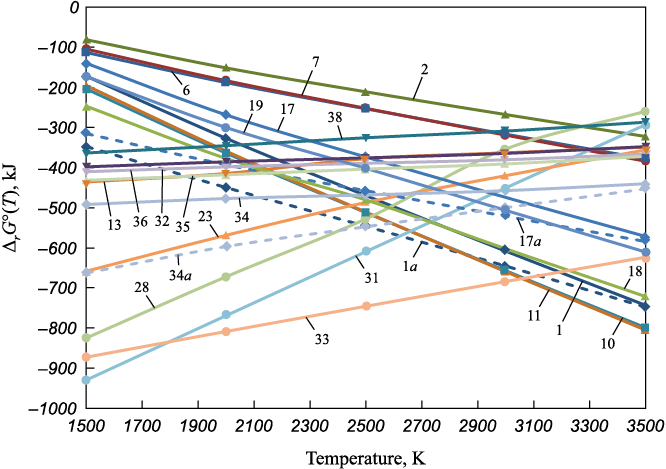

An analysis of the Table data shows that at 1500 K ∆r G°(T) changes from +58.44 kJ for reaction (32) to –929.12 kJ for reaction (31), and at 3500 K, it changes from +1389.31 kJ for reaction (32) to –803.92 kJ for reaction (11). Given such significant differences in ∆r G°(T) values, it makes sense to focus on the most thermodynamically probable reactions. These reactions are marked with asterisks in the table, and the dependencies of ∆r G°(T) on temperature are shown in the Figure.

Standard Gibbs energies of reactions (1) – (38) depending on temperature |

Clearly, the graphs in the figure visually separate into three groups. The first group consists of the most probable reactions in the 1500 – 2500 K temperature range. These are reactions (31), (33), (28), (23) between gaseous WO3 and aluminum, forming liquid or gaseous aluminum oxides. In the gas phase, the formation of aluminum dimer (Al2) has a high probability of yielding tungsten with AlO2(g) up to 3000 K (reaction (33)).

The second and larger group includes reactions (1), (1a), (11), (17), (17a), (18), and (19), which have a high probability of occurring in the temperature range of 2500 – 3500 K. In these reactions, the reductants are carbon and silicon, known for their increasing reductive properties as temperatures rise. Carbon and silicon also tend to disproportionate when reacting with metal oxides, especially those of active metals. This results in high thermodynamic probabilities for reactions (11), (18), and (19), where, alongside the oxides CO(g) and SiO(g) (positive oxidation states of carbon and silicon), carbides and silicides of various compositions (negative oxidation states of carbon and silicon) are formed.

The third group includes reactions (34), (34a), (35), (36), (37), (38). These involve titanium, which does not readily vaporize or form gaseous oxides. Thus, the graphs show a slight upward slope, indicating less negative values ∆r G°(T) with increasing temperature. As with other reductants, the evaporation of WO3 enhances the thermodynamic likelihood of its reduction by titanium (reaction (34a)). It can be concluded that titanium is an effective reductant that performs well across the entire temperature range of the welding arc.

The analysis of the thermodynamic properties of the reactions showed that the presence of reductants (carbon, silicon, aluminum, titanium) alongside tungsten oxide (WO3) in the flux-cored wire used for surfacing, either separately or together, will promote the formation of tungsten silicides and carbides, and possibly elemental tungsten. Tungsten oxide exhibits the highest reactivity in its gaseous state WO3(g), which aligns perfectly with the physical properties of WO3 . In the literature, WO3 is described as “volatile upon calcination”.

Aluminum has the highest chemical affinity for gaseous tungsten oxide WO3(g) in the form of Al(g) and the dimer Al2(g) in the temperature range of 1500 – 3000 K. The most likely oxidation product of aluminum is Al2O(g), which suggests the absence of non-metallic inclusions of Al2O3(s) in the deposited metal. Thus, aluminum is the most effective reductant at relatively low temperatures in the arc.

Using silicon and carbon as reductants promotes the formation of both tungsten and its silicides and carbides in the metal melt due to disproportionation reactions, which are characteristic of these elements. Carbon and silicon are the most effective reductants at the highest temperatures in the arc.

Titanium is a quality reductant that performs its reductive functions across the entire temperature range of the welding arc. When titanium is used in the flux-cored wire, it is likely to produce TiO2(s) and Ti4O7(s) oxides as non-metallic inclusions in the deposited metal.

Conclusions

Based on the available thermodynamic data for the reactants, calculations were performed to determine the properties [∆r Н°(Т), ∆r S°(Т), ∆r G°(Т)] of the reactions involving the reduction of tungsten oxide (WO3) by carbon, silicon, aluminum, and titanium (41 reactions) in their standard states within the temperature range of 1500 – 3500 K.

The presence of reductants (carbon, silicon, aluminum, titanium) alongside tungsten oxide (WO3) in the flux cored wire used for surfacing, either individually or together, will promote the formation of tungsten silicides and carbides, and possibly elemental tungsten.

Aluminum has the highest chemical affinity for gaseous tungsten oxide WO3(g) in the forms of Al(g) and the dimer Al2(g) in the temperature range of 1500 – 3000 K. The most likely oxidation product of aluminum is Al2O(g), which suggests the absence of non-metallic inclusions of Al2O3(s) in the deposited metal. Thus, aluminum is the most effective reductant at relatively low temperatures in the arc. Using silicon and carbon as reductants promotes the formation of both tungsten and its silicides and carbides in the metal melt. Titanium is an effective reductant across the entire temperature range of the welding arc, and its use is likely to result in the formation of TiO2 and Ti4O7 oxides as non-metallic inclusions in the deposited metal.

The obtained data on the reduction of WO3 provide a basis for conducting practical experiments on incorporating tungsten oxide and reductants into the composition of the flux cored wire charge.

References

1. Li W., Wang H., Yu R., Wang J., Wang J., Wi M., Maksimov S.Yi. High-speed photography analysis for underwater flux-cored wire arc cutting process. Transactions on Intelligent Welding Manufacturing. 2020:141–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8192-8_7

2. Eremin E.N., Losev A.S., Ponomarev I.A., Borodikhin S.A., Volochayev M.N. Wear resistance of steel obtained by surfacing a flux-cored wire 30N8Kh6M3STYu. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2020;1546:012060. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1546/1/012060

3. Moreno J.R.S., Guimarães J.B., Lizzi E.A. da S., Correa C.A. Analyze and optimize the welding parameters of the process by pulsed tubular wire (FCAW – Flux Cored Arc Welding) based on the geometry of the weld beads resulting from each test. Journal of Material Science and Technology Research. 2022;9(1):11–23. https://doi.org/10.31875/2410-4701.2022.09.02

4. Il´yaschenko D.P., Zernin E.A., Sapozhkov S.B., Loskutov L.G. Method for predicting the composition of the protective coating in MMA. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2020;939:012029. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/939/1/012029

5. Kobernik N.V., Pankratov A.S., Sorokin S.S., Petrova V.V., Galinovskii A.L., Orlik A.G., Stroitelev D.V. Effect of chromium carbide introduced into a flux cored wire charge on the structure and properties of the hardfacing deposit. Russian Metallurgy (Metally). 2020;2020(13):1485–1490. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0036029520130145

6. Wu W., Zhang T., Chen H., Peng J., Yang K., Lin S., Wen P., Li Z., Yang S., Kou S. Effect of heat input on microstructure and mechanical properties of deposited metal of E120C-K4 high strength steel flux-cored wire. Materials. 2023;16(8):3239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16083239

7. Smolentsev A.S., Votinova E.B., Veselova V.E., Balin A.N. Study of microstructure and properties of high-strength alloy steel welded joints made with austenitic flux-cored wire with nitrogen. Metallurgist. 2023;67(7-8):928–937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11015-023-01582-5

8. Liu H.-Yu., Song Zh.-L., Cao Q., Chen S.-P., Meng Q.-S. Microstructure and properties of Fe-Cr-C hardfacing alloys reinforced with TiC-NbC. Journal of Iron and Steel Research, International. 2016;23(3):276–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1006-706x(16)30045-0

9. Malushin N.N., Gromov V.E., Romanov D.A., Bashchenko L.P., Kovalev A.P. Development of complex hardening technology of cold rolling rolls by plasma surfacing. Zagotovitel’nye proizvodstva v mashinostroenii. 2023;21(7): 296-302. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.36652/1684-1107-2023-21-7-296-302

10. Ryabtsev I.A., Lentyugov I.P., Bezushko O.N., Goncharova O.N., Ryabtsev I.I., Lukyanenko A.A. Influence of methods of preparation of a charge of flux-cored wires on the structure of the deposited metal and the environmental safety of the working area during arc surfacing. Welding Production. 2022;(8):47–53. (In Russ.).

11. Malushin N.N., Martyushev N.V., Valuev D.V., Karlina A.I., Kovalev A.P., Gizatulin R.A. Strengthening of metallurgical equipment parts by plasma surfacing in nitrogen atmosphere. Metallurgist. 2022;65(11-12):1468–1475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11015-022-01292-4

12. Vinokurov G.G., Vasil’eva M.I., Kychkin A.K., Moskvitina L.V. Structure and tribological properties of the wear-resistant coatings deposited using flux-cored wires modified by tantalum and tungsten. Russian Metallurgy (Metally). 2019;2019(13):1357–1362. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0036029519130391

13. Ma Q., Li H., Liu S., Liu D., Wang P., Zhu Q., Lei Y. Comparative evaluation of self-shielded flux-cored wires designed for high strength low alloy steel in underwater wet welding: Arc stability, slag characteristics, and joints’ quality. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance. 2022;31(4): 5231–5244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-022-06683-x

14. Zou Z., Liu Z., Han X. Effect of W on microstructure and properties of Fe-Cr-C-W-B surfacing alloy. Transactions of the China Welding Institution. 2021;42(7):91–96. https://doi.org/10.12073/j.hjxb.20210208001

15. Smolentsev A.S., Veselova V.E., Berezovsky A.V., Usoltsev E.A., Shak A.V. Structure and properties of welded joints of high-strength steels made by metal-core wire with nitrogen. Metallurg. 2023;(9):71–77. (In Russ.).

16. Malushin N.N., Romanov D.A., Kovalev A.P., Bashchenko L.P., Semin A.P. Stress state in deposited steel cast rolls with high surface hardness after argon plasma-jet hard-facing. Russian Physics Journal. 2022;64(12):2185–2192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11182-022-02575-8

17. Pandova I., Makarenko V., Mitrofanov P., Dyadyura K., Hrebenyk L. Influence of non-metallic inclusions on the corrosion resistance of stainless steels in arc surfacing. MM Science Journal. 2021;2021(6):4775–4780. https://doi.org/10.17973/MMSJ.2021_10_2021032

18. Malushin N.N., Kovalev A.P., Smagin D.A. The choice of a surfacing method for hardening parts of mining and metallurgical equipment. Bulletin of Scientific Conferences. 2015; (2-1(2)):105–106. (In Russ.).

19. Thermodynamic Properties of Individual Substances: Reference. Vol. 1. Book 1. Glushko V.P., Gurvich L.V., etc. eds. Moscow: Nauka; 1978:440. (In Russ.).

20. Barin I., Knacke O., Kubaschewski O. Thermochemical Properties of Inorganic Substances. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1977.

21. Kryukov R.E., Goryushkin V.F., Bendre Yu.V., Bashchenko L.P., Kozyrev N.A. Thermodynamic aspects of Cr2O3 reduction by carbon. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2019;62(12):950–956. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2019-12-950-956

22. Bendre Yu.V., Goryushkin V.F., Kryukov R.E., Kozyrev N.A., Shurupov V.M. Some thermodynamic aspects of WO3 recovery by silicon. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2017;60(6):481–485. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2017-6-481-485

23. Bendre Yu.V., Goryushkin V.F., Kozyrev N.A., Shevchenko R.A., Oznobikhina N.V. Thermodynamic aspects of metal oxides reduction by aluminum and titanium during thermite welding of rails. Bulletin of the Siberian State Industrial University. 2021;3(37):13–19. (In Russ.).

About the Authors

L. P. BashchenkoRussian Federation

Lyudmila P. Bashchenko, Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Assist. Prof. of the Chair “Thermal Power and Ecology”

42 Kirova Str., Novokuznetsk, Kemerovo Region – Kuzbass 654007, Russian Federation

Yu. V. Bendre

Russian Federation

Yuliya V. Bendre, Cand. Sci. (Chem.), Assist. Prof. of the Chair of Ferrous Metallurgy and Chemical Technology

42 Kirova Str., Novokuznetsk, Kemerovo Region – Kuzbass 654007, Russian Federation

N. A. Kozyrev

Russian Federation

Nikolai A. Kozyrev, Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Deputy Director of the Scientific Center for High-Quality Steels

23/9 Radio Str., Moscow 105005, Russian Federation

A. R. Mikhno

Russian Federation

Aleksei R. Mikhno, Director of the Scientific and Production Center “Welding Processes and Technologies”

42 Kirova Str., Novokuznetsk, Kemerovo Region – Kuzbass 654007, Russian Federation

V. M. Shurupov

Russian Federation

Vadim M. Shurupov, Postgraduate of the Chair of Ferrous Metallurgy and Chemical Technology

42 Kirova Str., Novokuznetsk, Kemerovo Region – Kuzbass 654007, Russian Federation

A. V. Zhukov

Russian Federation

Andrei V. Zhukov, Postgraduate of the Chair of Ferrous Metallurgy and Chemical Technology

42 Kirova Str., Novokuznetsk, Kemerovo Region – Kuzbass 654007, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Bashchenko L.P., Bendre Yu.V., Kozyrev N.A., Mikhno A.R., Shurupov V.M., Zhukov A.V. Thermodynamic aspects of WO3 tungsten oxide reduction by carbon, silicon, aluminum and titanium. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2024;67(4):449-456. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-4-449-456

JATS XML