Scroll to:

Estimation of accident rate of blast furnace tuyeres

https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-2-148-154

Abstract

In modern blast furnace production, even a short-term disruption of the technological process is associated with large productivity losses. In the practice of conducting blast furnace melting, there are often significant deviations from the optimal mode. They can lead not only to disruptions of the blast furnace, but also to accidents. In the operation of a blast furnace, typical deviations from the normal distribution of gas flow and charge materials include: peripheral, axial, channel passages; skewing of the backfill level; varying degrees and types of charge suspension. As a result, there are a cooling or excessive overheating of the furnace and violation of the melting operation. A serious consequence of the prolonged peripheral movement of gases is not only intensive wear of the lining, poor use of thermal and chemical energy of gases, but also stable cluttering of the hearth with formation of a deadman. Deadman is an ore-coke sinter formed in the tuyere zone of a blast furnace, as a result of cooling of its center. The paper describes the study and analysis of violations of blast furnace operation, analysis of the deadman causes and assessment of the accident rate of blast furnace tuyeres. Violation of gas distribution and hearth cluttering lead to formation of a deadman, which provokes mass burning of tuyeres and blast furnace refrigerators. The developed methodological foundations (mathematical model) allow us to estimate the maximum temperature of the tuyere zone and the resulting heat flow to the tuyere toe in presence of a deadman. It is shown that in large-volume blast furnaces, bubble outflow of the gas-coal flow prevails, contributing to growth of a deadman in the blast furnace.

Keywords

For citations:

Stuk T.S., Pototskii E.P. Estimation of accident rate of blast furnace tuyeres. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2024;67(2):148-154. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-2-148-154

Introduction

As of today, the industrial safety policy of metallurgical companies is based on the assertion that accidents and emergencies at production facilities can be prevented. Therefore, to prevent accidents at enterprises, various methods for hazard analysis and risk assessment are actively implemented and used.

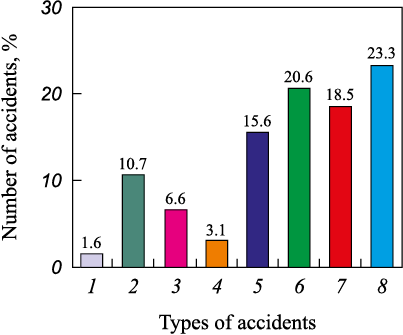

Despite the trend towards reducing the number of accidents, the frequency of incidents in metallurgical production remains consistently high. The number of accidents ranges from 4 to 9 annually, but their distribution across different metallurgical production processes varies1 (Fig. 1). The most hazardous processes include blast furnace, oxygen converter, electric furnace steelmaking, and coke-chemical productions.

Fig. 1. Distribution of accidents by type of production: |

The most severe types of accidents in blast furnace production involve the removal of pig iron and/or slag from metallurgical units, breakthrough of the hearth, refrigerators, and air ducts of blast furnaces, as well as explosions in metallurgical units caused by the supply of charge materials and tuyere burnouts [1; 2].

According to the 2020 report by PJSC NLMK, blast furnace tuyeres failed more than 200 times (Fig. 2). Fig. 3 presents the statistics of blast furnace tuyere failures as a percentage.

Fig. 2. Main types of accidents:

Fig. 3. Failure statistics of blast furnace tuyeres |

Typical deviations from the normal distribution of gas flow and charge materials include peripheral, axial, and channel passages; skewing of the backfill level; and various degrees and types of charge suspension, including the so-called “tight” run [3; 4]. Consequently, the furnace may experience cooling or excessive overheating, overloading of the axial zone with mineral charge, and violation of the melting operation. These conditions can lead to the cluttering of the hearth and frequent burning of the air tuyeres. Prolonged channel passages result in uneven burnout of the profile or stagnation of charge materials, leading to the formation of accretions [5].

Hearth cluttering in blast furnaces adversely affects the thermal mode, necessitating a reduction in ore loads. In the hearth, significant amounts of graphite form at lower temperatures [6]. The heating of the hearth deteriorates due to the formation of peripheral passages, as there is a decrease in heating when unprepared charge material is loaded [4]. Cold ferriferrous slag forms on the tuyeres.

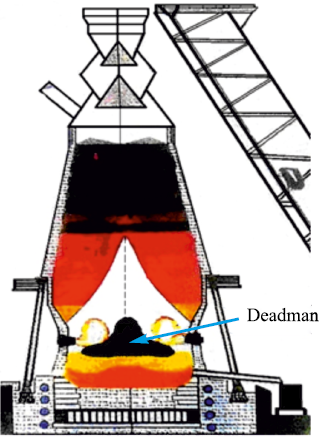

The infiltration of water vapor into the hearth through burnouts of cooling equipment is further exacerbated by the overloading of the low-mobility zone in the presence of low kinetic energy [7]. This deviation leads to the cluttering process in the tuyere belt of the blast furnace. As the cluttering zone expands, the burning of tuyere connections intensifies, as depicted in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Hearth cluttering with ore-coke sinter |

A severe disruption of the smelting process is the clogging of the hearth [4; 8]. It contributes to the deterioration of the gas dynamics of the process and significantly reduces the working space of the iron receiver. This hinders the movement of molten iron in the hearth and clogs the space in front of the tuyere nose. When the center of the blast furnace hearth cools, coke and slag begin to compress into a monolith due to the fine fraction of the charge material [9; 10]. This leads to poor filtration in the hearth, thus making it difficult for the smelting products to flow into the blast furnace iron receiver.

Despite the numerous developed and applied methods for assessing the risk of accidents in blast furnace production, a methodology is needed that can account for the specific operational characteristics of the blast furnace, considering the formation of the deadman in the tuyere zone and the increase in temperature in the tuyere zone with subsequent tuyere burnout, etc. Therefore, improving the methodology for assessing the accident risk of blast furnace tuyeres, taking into account the formation of the deadman, is currently a relevant task.

Description of the research method

A significant contribution to the study of tuyere zone cluttering has been made by the National University of Science and Technology MISiS (NUST MISiS) through the efforts of Zherebin B.N., Vegman E.F., Parenkov A.E., and others [1; 11]. It is known that large-volume blast furnaces (Blast Furnace No. 5 of the Kryvorizhstal plant) are prone to the formation of large scabs, including ore-coke sinter, in the central part of the hearth. The boulder-like formation (deadman), with its peak reaching the level of the bosh, consists of refractory carbides and carbonitrides. The deadman obstructs normal gas distribution and promotes the formation of a peripheral flow in the blast furnace [12; 13]. The tuyere blast reflects off the surface of the deadman onto the furnace lining and hearth refractory. This leads to a deterioration in the durability of the refractory and contributes to an emergency situation due to the breakthrough of high-temperature smelting products in the blast furnace.

This work proposes a methodology for assessing the accident rate of blast furnace tuyeres under the influence of a deadman.

In blast furnaces, two stable hydrodynamic outflow modes are realized: jet and bubble [14; 15]. The jet mode of flow is characteristic of normal gas distribution in the blast furnace, whereas the bubble mode of flow promotes the growth of the deadman.

The value of the Glinkov criterion Gn is determined by the formula

| \[{G_n} = \frac{{{\rho _{\rm{g}}}w_{\rm{g}}^2}}{{{\rho _{\rm{j}}}g{h_{\rm{j}}}}},\] | (1) |

where ρg is the effective density of the flow, kg/m3; wg is the gas velocity at the tuyere exit, m/s; ρj is the density of the melt in the tuyere zone, kg/m3; g is the acceleration due to gravity, m/s2; and hj is the distance from the tuyere axis to the melt, m.

The effective density of the flow is calculated using the formula

| рg = Qair ρhb + Qng ρng + Qcoal ρcoal , | (2) |

where Qair , Qng , Qcoal are the volumetric fractions of “air + oxygen,” natural gas, and pulverized coal; ρhb , ρng , ρcoal are the densities of hot blast, injected natural gas, and pulverized coal.

The density of the hot blast is calculated using the formula

| \[{\rho _{{\rm{hb}}}} = \rho _0^{}\frac{{P{T_0}}}{{{P_0}{T_{\rm{b}}}}},\] | (3) |

where ρhb is the density of the hot blast, kg/m3; ρ0 is the density of air under normal conditions, kg/m3; Р is the pressure of the hot blast, atm; Р0 is the atmospheric pressure, atm; Т0 is the ambient temperature, K; Тb is the blast temperature, K.

Density of the injected natural gas is determined using the formula

| \[{\rho _{{\rm{ng}}}} = \rho _0^{{\rm{ng}}}\frac{P}{{{P_0}}},\] | (4) |

where \(\rho _0^{{\rm{ng}}}\) is the density of natural gas, kg/m3.

If the Glinkov criterion is less than one, a bubble mode is present; if the Glinkov criterion exceeds three, the flow mode is jet. Intermediate values indicate a transitional flow mode.

The heat transfer from the deadman primarily occurs through radiation and convection. To calculate the resultant heat flow to the tuyere nose, it is necessary to determine the temperature of the internal blowing zone and the hydrodynamic blowing mode of the blast furnace. The temperature of the blowing zone corresponds to the surface temperature of the deadman [1].

The surface temperature of the deadman Tt can be calculated from the heat balance equation using the formula [16]

| \[\begin{array}{c}{T_t} = \frac{{0.165{T_f}{V_{{\rm{bost}}}}}}{{d_h^3}} + 2.445(B - 483) + 2.91({T_{\rm{j}}} - 107) - \\ - 11.2({\eta _{{\rm{CO}}}} - 27.2) + 28.9({d_{{\rm{proke}}}} - 25.8) + 326,\end{array}\] | (5) |

where Tf is the theoretical combustion temperature, °С; Vbost is the volume of gas in the bosh, mm3/min; dh is the diameter of the hearth, m; B is the fuel consumption, kg/t; Tj is the index of slag fluidity; ηCO is the CO content in the furnace center (from the shaft); dproke is the diameter of coke particles in the deadman, mm.

The index of slag fluidity (Tj ) is calculated using the formula

| \[{T_{\rm{j}}} = {T_{{\rm{mi}}}} - \left\{ {342\left( {\frac{{{\rm{CaO}}}}{{{\rm{Si}}{{\rm{O}}_2}}}} \right) + 11.0\left[ {({\rm{A}}{{\rm{l}}_2}{{\rm{O}}_3}) + 1.4} \right] + 819} \right\},\] | (6) |

where Тmi is the temperature of the molten iron, °С; \(\left( {\frac{{{\rm{CaO}}}}{{{\rm{Si}}{{\rm{O}}_2}}}} \right)\) is the basicity of the slag; and (Al2O3) concentration of Al2O3 in the slag, %.

The size of the blowing zone, i.e., the zone where the horizontal gas-liquid flow and the reaction zone are located, is determined using the formula

| \[{l_{{\rm{bz}}}} = 5.44{d_0}{\left( {{G_n}\frac{{{H_0}}}{{{d_0}}}} \right)^{0.24}},\] | (7) |

where lbz is the length of the blowing zone, m; H0 is the height of the liquid bath, m; d0 is the inner diameter of the tuyere nose, m.

The effective emissivity of the tuyere nose is calculated using the formula

| \[{\varepsilon _{{\rm{ef}}}} = \frac{1}{{1 + \left( {\frac{1}{{{\varepsilon _1}}} - 1} \right)\frac{S}{{{S_l}}}}},\] | (8) |

where εef is the effective emissivity of the tuyere nose; εl is the emissivity of the tuyere nose (assumed to be 0.6); Sl is the area of the inner surface of the blowing zone, m; S is the area of the metal casing of the tuyere nose, m2.

The area of the metal casing of the tuyere nose S is determined using the formula

| \[S = 0.785\left( {d_{\rm{n}}^2 - d_0^2} \right),\] | (9) |

where dn is the outer diameter of the tuyere nose, m; d0 is the inner diameter of the tuyere nose, m.

The area of the inner surface of the blowing zone Sl is calculated using the formula

| Sl = πdn lbz , | (10) |

where lbz is the length of the blowing zone, m.

The resultant heat flow q\(^p\) to the tuyere nose [13] is calculated using the Stefan-Boltzmann law:

| \[{q^p} = {\varepsilon _{{\rm{ef}}}}\sigma \left( {T_t^4 - T_1^4} \right),\] | (11) |

where εef is the effective emissivity of the tuyere nose; σ is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, equal to 5.67·10\(^–\)8 W/(m2·K4); Tt is the surface temperature of the deadman, K; Т1 is the temperature of the multiphase flow at the tuyere section, K.

Conducted research and analysis of its results

It is assumed that from the furnace throat to the bosh, there is a dense layer through which the ascending gases filter. The bubbling layer is located in the zone between the bosh and the hearth [15; 17]. The charge in the bubbling layer is in a liquid state. The blast streams, in addition to air, oxygen, and natural gas, carry pulverized coal particles [18]. According to Table 1, the Glinkov criterion was determined.

Table 1. Initial data for calculating the Glinkov criterion

|

Using formulas (3) and (4), the values ρhb = 0.61 kg/m3, ρng = 2.08 kg/m3 were determined. The effective density of the flow, calculated using formula (2), is 0.79 kg/m3, and the Glinkov criterion, using formula (1), is 0.27, indicating a bubble mode for the gas-coal flow in the blast furnace.

Next, the average surface temperature of the deadman was determined. The initial data for the calculation are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Initial data for calculating the average deadman temperature

|

Using formula (6), the index of slag fluidity Тf was calculated to be 837 °C, and the surface temperature of the deadman Tt using formula (5), was 2331 °C, which exceeds the theoretical combustion temperature by 231 °C.

To calculate the resultant heat flow on the tuyere nose of the blast furnace, we assume the following:

– the blowing zone is a cylindrical cavity with a diameter equal to the outer diameter of the tuyere;

– the surface temperature of the deadman Tt is 2331 °С;

– the output parameters of the tuyere, including the multiphase flow at this section, have a temperature T1 of 800 °С;

– the gas flow in the blowing zone is filled with coal particles and melt droplets [18]. Radiation in this zone follows the laws of blackbody radiation.

The initial data for calculating the heat flux to the tuyere nose are presented in Table 3.

The length of the blowing zone, determined using formula (7), is 1.43 m. The effective emissivity of the tuyere nose, calculated using formula (8), is 0.953. The area of the metal casing of the tuyere nose S, determined using formula (9), is 0.033 m2, and the area of the inner surface of the blowing zone Sl using formula (10), is 1.123 m2. The resultant heat flow q\(^p\) to the tuyere nose, determined using formula (12), is 2.3 MW/m2.

Table 3. Initial data for calculating the heat flow on tuyere toe

|

In stationary mode (heating the tuyere), there is local contact between the tuyere nose and the pig iron. The allowable resultant flux on the tuyere nose should not exceed 2.1 MW/m2 [19], indicating that further reducing the cooling water temperature for the tuyere is impractical and leads to thermal stresses. This reduction decreases the lifespan of the tuyere device and can provoke mass tuyere burnouts.

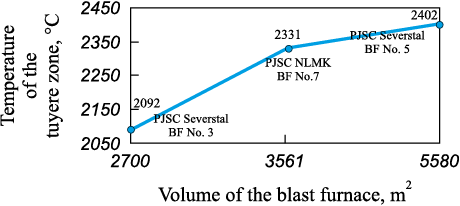

The increase in tuyere zone temperature for different volumes of blast furnaces indicates the need for additional measures to prevent tuyere burnouts. Fig. 5 shows this dependence.

Fig. 5. Dependence of tuyere zone temperature on blast furnace volume |

Thus, the surface temperature of the deadman depends on the volume of the blast furnace. The temperature rise negatively impacts the safe operation of large-volume blast furnaces, increasing the likelihood of gas explosions and reducing the lifespan of tuyere devices.

Accidents involving mass tuyere burnouts are associated with intense vaporization. They are accompanied by a large amount of water entering the blast furnace [20]. The resulting steam breaches from beneath the layers of pig iron and slag cause chain-like thermal explosions.

Recommendations for preventing tuyere burnout

The study proposes measures to prevent tuyere burnout depending on the volume of the blast furnace and the temperature of the tuyere zone.

For blast furnaces with a volume up to 2700 m3 and a tuyere zone temperature up to 2100 °С:

– automated analysis of retrospective data on the statistical properties of cooling water flow rate variations;

– analysis of silicon content in pig iron.

For blast furnaces with a volume of 2700 – 3500 m3 and a tuyere zone temperature of 2100 – 2300 °C:

– automated analysis of retrospective data on the statistical properties of cooling water flow rate variations;

– analysis of silicon content in pig iron;

– the nose of the air tuyere must be protected with refractory materials, including plasma spraying;

– the inner sleeve of the tuyere must be made of steel plate instead of copper, with additional lining of refractory materials.

For blast furnaces with a volume of 3500 – 5560 m3 and a tuyere zone temperature of 2300 – 2400 °С:

– automated analysis of retrospective data on the statistical properties of cooling water flow rate variations;

– analysis of silicon content in pig iron;

– the nose of the air tuyere must be protected with refractory materials, including plasma spraying;

– the inner sleeve of the tuyere must be made of steel plate instead of copper, with additional lining of refractory material;

– cooling water supply mode for the tuyere:

а) technical water speed up to 11.6 m/s (normal water flow 4 – 5 m/s);

b) water flow rate 30 m3/h (normal water flow 12 – 16 m3/h);

c) water pressure 15 atm (normal water pressure 5 – 6 atm).

This regime requires the installation of high-pressure pumps and more robust equipment:

– the tuyere nose thickness should be no less than 40 – 50 mm;

– slag viscosity should not exceed 4 – 5 poise, and the loading of acidic pellets should be avoided.

Conclusions

It has been determined that the disruption of normal gas distribution and hearth cluttering leads to the formation of a blast furnace deadman, which provokes mass burning of tuyeres and refrigerators.

It is shown that in large-volume blast furnaces, the bubble flow of the gas-coal flow predominates, promoting the growth of the deadman, which can lead to increased accidents involving tuyere devices.

The proposed methodology (mathematical model) allows for the assessment of the maximum temperature of the tuyere zone and the resultant heat flow to the tuyere nose in the presence of a deadman.

Based on the calculated temperature of the tuyere zone, measures are proposed to prevent tuyere burnout depending on the volume of the blast furnace.

References

1. Zherebin B.N., Paren’kov A.E. Malfunctions and Accidents in the Operation of Blast Furnaces. Novokuznetsk; 2001:275. (In Russ.).

2. Pototskii E.P., Lazareva T.S. Analysis of stability and technological process of a blast furnace. In: “Energy-Efficient and Resource-Saving Technologies in Industry. Furnace Units. Ecology”. Proceedings of the IX Int. Sci. and Pract. Conf. 2018, Moscow. Moscow: MISIS; 2018:169–173. (In Russ.).

3. Tarasov V.P., Khairetdinova O.T., Tomash A.A. On gas permeability of softening zone in conditions of blast furnace melting. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2002;45(4):64–66. (In Russ.).

4. Dmitriev A.N., Shumakov N.S., Leont’ev L.I., Onorin O.P. Fundamentals of Theory and Technology of Blast Furnace Melting. Yekaterinburg: UB RAS; 2005:547. (In Russ.).

5. Tarasov V.P., Tarasov P.V., Bykov L.V. Gas-dynamic parameters and performance indicators of blast furnaces with loading of BLT to carrier-loader. Stal’. 2005;(1):6–9. (In Russ.).

6. Grigor’ev B.A., Tsvetkov F.F. Heat and Mass Transfer. Moscow: MEI; 2005:93. (In Russ.).

7. Mastryukov B.S. Safety in Emergency Situations in Natural and Man-Made Sphere. Forecasting the Consequences. Moscow: Academy; 2015:368. (In Russ.).

8. Hatano M.I. Influence of the method of loading the furnace profile, surface of the liquid phase on the gas flow in the blast furnace. Moscow: From Science; 2004:168.

9. Power D.J. Web-based and model-driven decision support systems: concepts and issues. In: AMCIS 2000, America’s Conference on Information Systems. California; 2000:173–186.

10. Anosov V.G., Fomenko A.P., Krutas N.V., Tsaplina T.S. On technology of blast furnace melting using pulverized coal fuel. Metalurgіya. Naukovі pratsі ZDІA. 2009;(20):37–43. (In Ukr.).

11. Vegman E.F., Zherebin B.N., Pokhvisnev A.N., Yusfin Yu.S., Kurunov I.F., Paren’kov A.E., Chernousov P.I. Ironmaking. Moscow: Akademkniga; 2004:774. (In Russ.).

12. Gorban A.N., Zinovyev A.Y. Principal graphs and manifolds. In: Handbook of Research on Machine Learning Applications and Trends: Algorithms, Methods, and Techniques. Chapter 2. Hershey, PA; 2009:28–59. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-766-9.ch002

13. Radyuk A.G., Titlyanov A.E., Sidorova T.Y. Modeling of the thermal state of air tuyeres of blast furnaces. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2016;59(9):622–627. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2016-9-622-627

14. Dolinskii V.A., Nikitin L.D., Koverzin A.M., Portnov L.V., Bugaev S.F. Use of washing briquettes for improvement of the blast-furnace hearth operation. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2013;56(2):33–36. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2013-2-33-36

15. Dai B., Long H.M., Ji Y.L., Rao J.T., Liu Y.C. Theoretical and practical research on relationship between blast air condition and hearth activity in large blast furnace. Metallurgical Research and Technology. 2020;117(1):113–117. https://doi.org/10.1051/metal/2020007

16. Pototskiy E. P., Lazareva T. S. Investigation of factors affecting the safety of a blast furnace operation. CIS Iron and Steel Review. 2022;(1):15–18. https://doi.org/10.17580/cisisr.2022.01.03

17. Song L., Xiaojie L., Qing L., Xusheng Z., Yana Q. Study on the appropriate production parameters of a gas-injection blast furnace. High Temperature Materials and Processes. 2020;39(1):10–25. https://doi.org/10.1515/htmp-2020-0005

18. Levitskii I.A., Radyuk A.G., Titlyanov A.E., Sidorova T.Yu. Influence of the method of natural gas supplying on gas dynamics and heat transfer in air tuyere of blast furnace. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2018;61(5):357–363. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2018-5-357-363

19. Yasuo O. Blast Furnace Phenomena and Modelling. New York: Elsevier Applied Science; 1987:631.

20. Feng Q., Wang L. Blast furnace hoist charging control system based on ActiveX technology. WIT Transactions on Information and Communication Technologies. 2014;46:1853–858.

About the Authors

T. S. StukRussian Federation

Tat’yana S. Stuk, Leading Specialist on Occupational Safety, Postgraduate of the Chair of Technosphere Safety

4 Leninskii Ave., Moscow 119049, Russian Federation

E. P. Pototskii

Russian Federation

Evgenii P. Pototskii, Cand. Sci. (Eng.)

4 Leninskii Ave., Moscow 119049, Russian Federation

Review

For citations:

Stuk T.S., Pototskii E.P. Estimation of accident rate of blast furnace tuyeres. Izvestiya. Ferrous Metallurgy. 2024;67(2):148-154. https://doi.org/10.17073/0368-0797-2024-2-148-154